State of the Union

Though the political references in Lindsay & Crouse’s Pulitzer Prize winner are all 1940’s, the themes of integrity and honesty in political campaigns are relevant all over again.

Jamahl Garrison-Lowe as Spike MacManus, Kyle Minshew as Grant Matthews and Jennifer Reddish as Kay Thorndyke in a scene from Metropolitan Playhouse’s revival of Lindsay and Crouse’s “State of the Union” (Photo credit: David Patlut)

[avatar user=”Victor Gluck” size=”96″ align=”left” ] Victor Gluck, Editor-in-Chief[/avatar]Howard Lindsay and Russel Crouse’s 1946 Pulitzer Prize winning political play, State of the Union, should be, by all accounts, dated in its depiction of the 1948 presidential political campaign with 1940’s references to people no longer household names. However, it seems more relevant than ever thanks in part to Laura Livingston’s smart and sassy revival for Metropolitan Playhouse, whose mission is to explore America’s diverse theatrical heritage. Her crackerjack production of this fast-paced political and romantic comedy moves like a house on fire and lands every one of its jokes. In addition, the play is so wise about the ways of backroom politics and Lindsay and Crouse have isolated a great many post-W.W. II issues that are now front page news again that this well-written and well-crafted comedy, although a period piece, has a great deal to say once more. Great fun will be had by all, both Republicans and Democrats, as well as independents.

The Democrats have been in the White House for four terms with Franklin D. Roosevelt and the Republicans are looking for a dark horse candidate to take back the White House. Washington operative James Conover, a big wheel in the National Committee, thinks he has found him in Grant Matthews, an airplane manufacturer tycoon and war hero who is not part of the political establishment. The problem is that Grant is too outspoken on high prices and low wages and there are rumors that he and his wife Mary are estranged: the talk is that he has been having an affair with newspaper tycoon Kay Thorndyke. As Grant is about to begin a tour of his plants across the mid-west and far west from Minneapolis to San Francisco to Detroit, Conover suggests that he invite his wife to join him on the tour so that she can be seen by his side and experience public life at first hand. Conover will decide after Detroit if Grant has what it takes to be a presidential candidate.

Anna Marie Sell as Mary and Kyle Minshew as Grant Matthews in a scene from Metropolitan Playhouse’s revival of Lindsay and Crouse’s “State of the Union” (Photo credit: Elizabeth Shane)

Surprisingly Mary is eager to go – possibly to scotch the rumors about Kay. However, she turns out to believe too much in honesty and integrity and as Conover attempts to teach her, a politician can never show his whole hand before he is elected. However, she feels that the country is being torn apart by special interest groups and that the politicians are attempting to divide and conquer. As Grant and Mary become close again, she disapproves of his trying to woo both big business and the labor unions. When Grant changes his speech in Detroit, the stage is set for a showdown between him and Mary at the political dinner she is talked into giving in New York. This is crucial because it is days before his speech to the Foreign Policy Association when it will become obvious that he is running for higher office. The climax is both surprising and dramatic – as well as satisfying.

Playwrights Lindsay and Crouse who wrote the longest running Broadway play of all time, a record they still hold since 1946 with Life with Father, have written a wise and witty play with a great deal of political intelligence still worth listening to. As Conover attempts to teach Mary, “You’re not nominated by the people – you’re nominated by the politicians! Why? Because the voters are too damned lazy to vote in the primaries. Well, politicians are not lazy.” On the international scene, Mary says, “While the war was on we were a united country – we were fighting Germany and Japan. Now, we’re fighting each other.” Sounds a lot like 2019. With the rise of lobbyists and political action committees (pacs) these remarks are true all over again after a gap of seventy years. On the domestic front, the judge’s wife declares, “Politics is too good an excuse for a man to neglect his wife” – which is probably still true, aside from the social media watching every step a public figure makes.

Jon Lonoff as Sam Parrish and Michael Durkin as James Conover in a scene from Metropolitan Playhouse’s revival of Lindsay and Crouse’s “State of the Union” (Photo credit: Vadim Goldenberg)

The play is studded with references to famous journalists and politicians of the early 1940’s from President Truman to Walter Lippmann to Senator Taft. However, there are also references to such figures as Drew Pearson, Westbrook Pegler, Huey Long, Wendell Wilkie, and Herbert Bayard Swope who are no longer familiar to all but historians. Nevertheless, the play and the production make it clear how to react to these names and the play still succeeds in spite of this.

The other major problem with the play is the casting: these recognizable characters are often played here against type. Best is Michael Durkin who brings great authority and restraint to the role of James Conover, redolent of 1940’s film heavies who specialized in such roles like Lionel Barrymore, Adolphe Menjou and Edward G. Robinson. Unfortunately, Grant and Mary are not quite as convincing. Kyle Minshew is decidedly light-weight as Grant and does not exude the kind of charisma that would rally voters around him. While Anna Marie Sell has a great deal of verve and is quick with a comeback, she fails to convince as the wife of a New York tycoon who would have been part of the highest social circle.

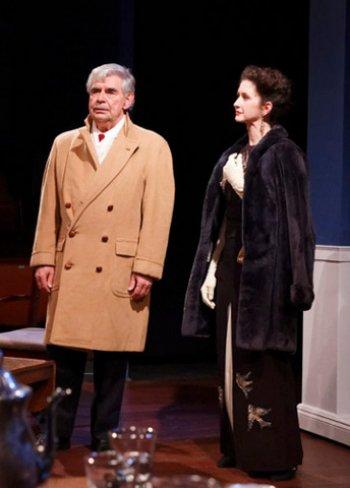

Michael Durkin as James Conover and Jennifer Reddish as Kay Thorndyke in a scene from Metropolitan Playhouse’s revival of Lindsay and Crouse’s “State of the Union” (Photo credit: Gloria Nelson)

As Spike MacManus, investigative reporter and now Grant’s manager, Jamahl Garrison-Lowe is a fine acerbic type who doesn’t let anything get past him. Jennifer Reddish’s Kay is perfect as a member of high society but not as convincing as a newspaper tycoon. On the other hand, Doug Hartwyk and Linda Kuriloff are hilarious as a doting Southern judge and his hard-drinking wife who tells it like it is. The rest of the political types seem to be at odds with the period. For example, labor union leader Bill Hardy as played by Milton Lyles seems more a collegiate type than a man who has worked his way up in the factory. His tuxedo fits him too well for him to complain how uncomfortable he is in it.

Vincent Gunn’s attractive setting is a model of economy with furniture and walls that are periodically rearranged for the four needed sets as the play moves from Conover’s Washington town house, to Detroit’s Book-Cadillac Hotel, and finally the Matthews’ Manhattan apartment. As always Sidney Fortner’s attractive costumes are redolent of the period, in this case 1947. Christopher Weston’s lighting is perfect for these mainly public spaces, while Michael Hardart’s sound design is fine as far as it goes, but at times we strain to hear the voices from the other rooms as implied by the play.

Linda Kuriloff as Lulubelle Alexander in a scene from Metropolitan Playhouse’s revival of Lindsay and Crouse’s “State of the Union” (Photo credit: Vadim Goldenberg)

Everything old is new again as the proverb says. Craftsmen Lindsay and Crouse (best known today for their librettos to Cole Porter’s Anything Goes, Irving Berlin’s Call Me Madam recently seen at New York City Center, and Rodgers and Hammerstein’s The Sound of Music) have written an entertaining and witty look at backroom politics which suddenly seems contemporary all over again. Laura Livingston’s high-powered production of State of the Union, which raised eyebrows when it won the Pulitzer Prize in 1946, proves to be an entertaining and sleekly well-oiled machine that has much to say to us today when divisive politics and politicians lacking in honesty and integrity are the name of the game.

State of the Union (through March 10, 2019)

Metropolitan Playhouse, 220 East 4th Street, in Manhattan

For tickets, call 800-838-3006 or visit http://www.metropolitanplayhouse.org

Running time: two hour and 50 minutes with one intermission

Leave a comment