Kafka and Son

Alon Nashman resembles a human fly or a vampire in his exhaustless and very physical performance as both the Czech author and his overbearing father.

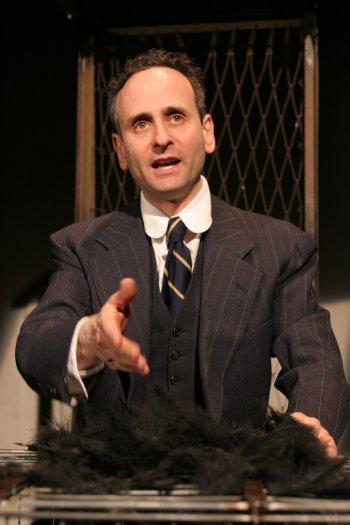

Alon Nashman in a scene from “Kafka and Son” (Photo credit: Cylla von Tiedemann)

[avatar user=”David Kaufman” size=”96″ align=”left”] David Kaufman, Critic[/avatar]Though not exactly a cockroach, Alon Nashman at times resembles a human fly or a vampire in his exhaustless and very physical performance in Kafka and Son. As conceived by Nashman and Mark Cassidy (who is also the director), the one-man show has him shuttling between portraying the timid, surrealist, Czech author, Franz Kafka, and his overbearing father, each with a distinctively different voice.

But Nashman seems to inhabit any other number of personas as well: the Jewish scholar and/or Klezmer dancer, the authority figure, the shrinking, uncertain human being who feels he’s a failure at everything. Nashman’s tour de force performance has him crouching in a cage like a wounded animal or standing on top of it in triumph–not to mention assuming every conceivable position in between.

Adapted from a 50-page letter that Kafka wrote to his emotionally abusive father, when he was 36 years old–and still living at home with his parents–the piece becomes like one of Kaka’s strangely bizarre, dreamscape fictions, providing strong evidence that his fictions were drawn from his life, and that his life was very much shaped by his father.

Alon Nashman in a scene from “Kafka and Son” (Photo credit: Cylla von Tiedemann)

From the beginning, Kafka is constantly contradicting himself, saying to his father, “You are entirely blameless” in one breath, and “as a father you have been too strong for me” in another, and “I was weighed down by your physical presence,” in yet another. He also, at one point, says, “You were for me the measure of all things,” and he blames his father for “tyrannizing” the staff at his dry-goods store, adding that he “sided with” the staff against his father. And if Kafka lived for his writing, he had to contend with his father’s “aversion” to it, adding, “My writing was all about you.”

Relatively early, Nashman as Kafka removes his three-piece checkered suit and strips down to his underpants, as he recalls swimming with his father. “I was proud of my father’s body,” he says, while describing how ashamed he was of his own. And though he frequently removes the jacket to be clad in a vest and matching pants–with a white, starched-collar shirt and necktie–Nashman is barefoot throughout, as if to emphasize how naked and exposed Kafka feels with every word he utters. (Barbara Singer receives credit for the costume.)

With only a metal-mesh cage, bed-frame, and a gate–and gobs of black feathers that ultimately litter the stage–Nashman cavorts around the black box set (scenic design is by Marysia Bucholc and Camellia Koo) with abandon. If the challenge of every one-man show is to sustain our attention, Nashman succeeds spectacularly. He has some significant help with evocative lighting by Andrea Lundy, eerie music by Osvaldo Golijov (performed by the St. Lawrence String Quartet), and Cassidy’s direction, which always keeps him in motion.

Kafka and Son (through October 22, 2017)

2017 International Fringe Encore Series

Theaturtle and Threshold Theatre, with Richard Jordan Productions in association with The Pleasance

SoHo Playhouse, 15 Vandam Street, in Manhattan

For tickets, visit http://www.sohoplayhouse.com

Running time: 65 minutes with no intermission

Leave a comment