CAROL CHANNING… A Personal Remembrance

I liked her tremendously. She always felt larger-than-life, even simply sitting quietly backstage, applying or removing her makeup. I loved watching her put on her makeup. She cared so much about every detail, even the smudge of gray she put on her nose to help give it better definition in the theater. "Create something every day," she'd urge me.

[avatar user=”Chip Deffaa” size=”96″ align=”left” ] Chip Deffaa, Editor-at-Large[/avatar]

Carol Channing, who just passed away, was my favorite person in this business, and the one who taught me the most.

To the world at large, she was a Broadway legend–one of the all-time greats of musical theater, a star since the 1940s. And she certainly was all of that!

Carol Channing

But to me, for several decades, she was an extraordinary friend, a kind of “fairy godmother.” A glorious burst of energy. I was so grateful to have her in my life. She was kind enough to make recordings for me, which appeared on albums I produced and in a musical comedy I wrote, “Theater Boys.” She did that as a gift, I m ust stress; she would not take a dime!

She’s had a profound influence on my life, and every time I direct a show, run a recording session, write a script, or hold an audition, I do so with guidance she gave me.

I’ve known no one more committed to her work than she was. No other actress in American has played any role as many times as Channing played Dolly Gallagher Levi in “Hello, Dolly!” She played the role–on Broadway and on national tours–some 5,000 times. And she performed it more than 4,500 times before ever letting an understudy go on. I’ve seen her go out on stage–on sheer nerves, putting mind over matter–despite fierce challenges to her health.

Carol Channing

No one knew it at the time, but she was fighting cancer during her first national tour in “Dolly”–flying back and forth to Sloan-Kettering Hospital in New York on her free day each week, to get treatments. As a longtime writer for The New York Post and as an autho0r working with various publishing houses, I never missed a deadline. I learned that discipline directly from Carol Channing. Lord knows, I certainly wasn’t disciplined by nature in my youth! But if she could do eight shows a week while fighting cancer, I could damn well write my copy for The Post, or another chapter of a book, with the Flu. She would tell me: “We do our best work when challenged.”I can hear her saying those words now, in that inimitable deep voice of hers. For me, she was like an oracle. I took very seriously her words. (In TV interviews, she would often affect an air of charming vagueness; but in private she was sharp and knowing.)

If I ever need a booster-shot of positive energy, I can listen to messages she’s left on my answering machine. She could wake me up with an early-morning phone call and it would guarantee a great week; I used to tell her she had a “healing voice.” When I’d tell her I loved that positive attitude of hers–that unflagging mind-over-matter approach to life that she had–she’d tell me she got it from her father, whom she idolized. She spoke about him at great length with me; he was a light-skinned African-American man, who passed for white.

On stage, in a musical comedy, no one could top her. She originated the roles of “Dolly Levi” in “Hello, Dolly!” and “Lorelei Lee” in “Gentleman Prefer Blondes.” She used to tell me, “Any actor is lucky if he gets to originate one great role. I got to originate two.”

Carol Channing and Tommy Tune

When you come into my home, the first things you’ll see are related to her–posters from the original Broadway runs of “Hello, Dolly!” and Lorelei, and a striking photographic portrait of her, taken by–and given to me by–her great good friend of five decades, Tommy Tune. (There was no one she liked more than Tommy.)

She taught me, when I was booking singers for a recording session, to always invite extras–teaching me that some singers would inevitably bail out at the last minute–sabotaging themselves by giving in to subconscious fears, she believed. And she was right; it would always happen.

She taught me to be tougher than I was by nature, when directing shows or producing recordings. “Chip, you have to be a benevolent dictator,” she would tell me. She had little tolerance for mediocrity. She strived to get along with people where possible, but if she felt anyone was weakening a production she was in, she’d deal with it promptly (And she had the strength to see to it that productions were to her liking.) If she was not happy with, say, the conductor on a tour she was starring in, she’d see to it he was replaced. She called the shots.

She was health-food conscious long before that was fashionable. On the road, she’d carry her own food with her. She avoided sugar, as if it were poison. (I’d give her sugar-free pastries.) For a while she tried giving up caffeine, but–ever the pragmatist–changed her mind when she concluded caffeine helped her learn lines better.

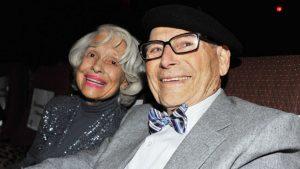

Carol Channing and husband Harry Kulijian

She encouraged me to dream big, grab opportunities when they came, and work full steam–and not to wait, because none of us know how much time we have. (I thought she’d live forever.) When she decided it was time to write her memoirs, she asked if I could meet with her. She told me she wasn’t a writer, she couldn’t possibly write a book by herself, and asked if we could do an “as told to” book together, with her telling me stories which I could put into book form. . She shared stories for hours that night, saying she hoped I could start writing the book at once. I told her I was so busy–I’d just moved and hasn’t even unpacked–it would be six weeks before I could begin work in earnest. Carol–who never believed in waiting–said she’d begin jotting down recollections until I was ready…. By the time I was ready, she’d actually finished writing the entire book herself in longhand. And it was a terrific book.

I liked her tremendously. She always felt larger-than-life, even simply sitting quietly backstage, applying or removing her makeup. I loved watching her put on her makeup. She cared so much about every detail, even the smudge of gray she put on her nose to help give it better definition in the theater. She did not wear false eyelashes–using mascara, she drew eyelashes on herself, which read just fine in the theater!

“Create something every day,” she’d urge me. “When we create, we’re closer to being whole and well.” She’d tell me that we’re all capable of doing much more than we might imagine. I never doubted her; she was living proof.

She was the consummate trouper. When she recorded the audio-book version of her autobiography, she spent hour after hour in front of the microphone (wearing only her bra and panties, to feel relaxed). She knew that time is money in a recording studio and did not want to take any breaks. Her producer, Steve Garrin, had to call breaks; she’d never call one herself. But she recorded the entire book–not an abbreviated version as many might do–spending 40 hours to record the complete book, plus some extras.

I loved spending time with her. I’d tell her I could learn more in an hour-long talk with her than I’d learned in four years of college. And I never knew what she might share next. She’d sing me African-American spirituals she’d learned as a child from her father. She could also impart wisdom in Yiddish, which she spoke well. (Her mother was Jewish.) She was raised in the Christian Science faith, and she’d tell me frankly what she thought was good or not-so-good about Christian Science.

She’d speak to me of performers she’d admired, from Fanny Brice to Lunt & Fontanne, to Mary Martin and Ethel Waters–becoming them, vocally, as she’d reminisce. She thought the world of Ethel Waters as both a person—she considered Waters a kind of godmother–and a performer. She could recall for me in exquisite detail the first time she saw Waters on stage in the early 1930s, singing “Supper Time”–a potent indictment of racism–in Irving Berlin’s revue “As Thousands Cheer.” She always felt a special bond with Waters.

She spoke movingly with me of visiting Mary Martin, less than an hour before Martin died. She told me she could see Martin’s aura, beautiful and colorful–the only time, she said, she ever saw someone’s aura; she believed Martin’s spirit was about to leave the body…. Carol said if it was up to her, her own remains would be interred next to the theater in San Francisco where she got her start; her life, she felt, really began at that theater, and she said it would be nicer to end up there than in a graveyard….

I’m going to miss picking up the phone and hearing Carol sing out… “Well, hello Chip….”

Wonderful woman. Wise. Gifted. And she put her gifts to great use. You can’t ask for more than that.

— CHIP DEFFAA, JANUARY 15th, 2019

Leave a comment