On The Town … with Chip Deffaa: Jerry Herman and Michael Feinstein

I liked Jerry Herman. I liked the man; he was endearing. And I liked his music. And he was one of the Broadway greats. Some of his songs–like some of Irving Berlin’s–are so simple, direct, and accessible–that sophisticates sometimes failed to appreciate them. But he spoke to the heart. And reached audiences well. He made Broadway a brighter place. Audiences left theaters humming his songs.

[avatar user=”Chip Deffaa” size=”thumbnail” align=”left”]Chip Deffaa, Editor-at-Large[/avatar]

My original plan was for my column this week was to focus exclusively on Michael Feinstein. But events overtook me, and today I’m going to write a bit about both Jerry Herman and Michael Feinstein. Hopefully I will be able to give Feinstein exclusive attention another time; he’s an important figure and he certainly deserves it. (Maybe another time I can do an interview with him. I’d like that.) But Herman’s passing is such a tremendous loss, I want to write a personal appreciation of him here, right away.

Jerry Herman

First, let me tell you a bit of background. On December 26th, 2019, I went into New York City to catch Michael Feinstein’s annual holiday show at his club, Feinstein’s 54 Below. Feinstein always gives us excellent shows, and I couldn’t think of a better place to be this time of year.

Michael Feinstein

Near the end of his show, after saluting such past masters as Irving Berlin and George & Ira Gershwin, Feinstein saluted Jerry Herman. It certainly seemed fitting. Herman very much belongs in the Great American Songbook tradition that such songwriters as Berlin and the Gershwins helped to establish.

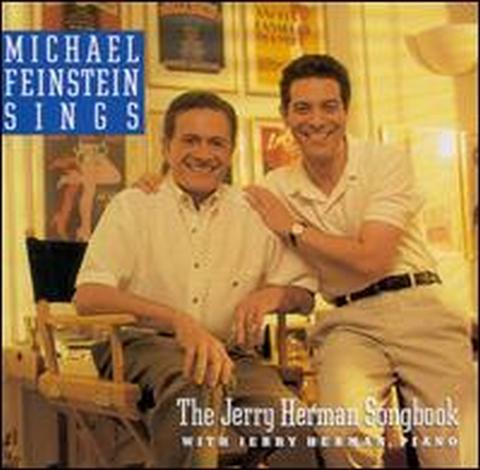

And Feinstein is perfectly equipped to interpret Herman’s open-hearted songs; he and Herman are a great natural “fit.” In fact, they once recorded a whole album together (which I’ll be listening to, once again, as soon as I finish writing this column)–“Michael Feinstein Sings the Jerry Herman Songbook.” On that album–part of an impressive songwriters’ series Feinstein has done–Herman played piano for Feinstein and even joined him for some vocal duets. And Herman composed a complete score for one musical, “Miss Spectacular,” that, sadly, was never produced. He chose Michael Feinstein to help record numbers from the show for a concept album. (If memory serves, he even had Feinstein contribute some additional lyrics.) So there’s a longtime connection between Jerry Herman and Michael Feinstein.

Michael Feinstein and Jerry Herman

But there I was the other night (December 26th), at the club, enjoying Feinstein’s rendition of Herman’s well-known “We Need a Little Christmas” (from “Mame”) and not-so-well-known but charming “The Best Christmas of All” (from “Mrs. Santa Claus”).

It warmed my heart to hear Feinstein tell us that Jerry Herman was still with us, enjoying the sunshine of Florida. I knew that Herman, at age 88, was in poor health. But just hearing Michael Feinstein perform two appealing songs of his and mention that Herman was still with us–down in sunny Florida–cheered me.

Michael Feinstein Sings “The Jerry Herman Song Book”

Afterwards, I made my way back to my home in New Jersey, too wired to go to sleep right away. (A good show will do that to me.) And late that same night–with some of Herman’s music still ringing in my ears–I received word from a friend that Jerry Herman had just died. I stayed up a little longer, to acknowledge Jerry Herman’s passing on Facebook. I was glad I’d heard some of

Herman’s music–sung by a leading interpreter of his songs–on the day he’d died.

And I’d like to share a few observations and recollections of Jerry Herman here.

Jerry Herman

* * *

Composer/lyricist Jerry Herman was, of course, a Broadway legend. He gave us such unforgettable shows as “Hello, Dolly!,” “Mame,” and “La Cage Aux Folles.” These musicals were all huge hits, brimming with songs that audiences quickly took their heart–songs like “We Need a Little Christmas,” I Am What I Am,” “If He Walked into My Life,” “The Best of Times,” and, of course, two of the most enduringly popular title-songs in Broadway history: “Hello, Dolly!” and “Mame.” Among his other Broadway shows: “Milk and Honey,” “Mack and Mabel,” “The Grand Tour,” “Dear World,” “Jerry’s Girls,” “An Evening with Jerry Herman.” He also contributed material to both “Ben Franklin in Paris” and “A Day in Hollywood/A Night in the Ukraine.”

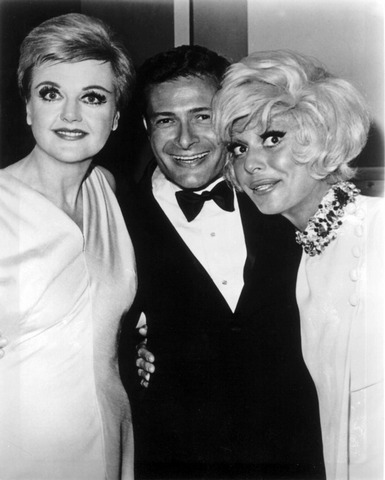

Jerry Herman with Angela Lansbury and Carol Channing

Offstage, Jerry Herman was a gentle, quiet, tremendously warm, self-effacing man–down-to-earth, and very easy to like. And when we talked, he was generous in his praise of others, and happy to talk about other songwriters he liked such as Kander & Ebb, and Cy Coleman.

Herman was, by nature, sensitive and somewhat of a loner. His work came first, and he spent much of his time by himself, crafting music and lyrics for songs. (A personal assistant/secretary, Sheila, long helped him as needed with matters like correspondence and scheduling.)

He was not really looking for–and did not find, until rather late in his life–a man to share his life with. Like his dear friend Carol Channing (who thought the world of him), he had a network of friends with whom he stayed in touch through the years largely by phone calls and letters. (He even “inherited” his late mother’s friends and for years stayed in touch with them as well.) He added a lot of happiness to the world. And it made me happy to hear from him.

I also always enjoyed hearing him perform his music himself; he had a lot of heart. I remember going to a backers’ audition–to raise money for the production of one of the shows–where he demonstrated all the songs, himself–and I enjoyed that backers’ audition as much as I did the eventual show itself. Of course, over the years, he had the pleasure of hearing his songs put across by the best in the business. (The photos I’m sharing show Herman with such notable interpreters of his music as Carol Channing, Angela Lansbury, and Lee Roy Reams)

* * *

Jerry Herman grew up in Jersey City–a middle-class kid who went to the theater all of the time. Theater was affordable to middle-class families back then in a way that it is not nowadays–as he once noted to me sadly, adding that had he been born at a later time it would have been impossible for him to immerse himself in theater the way he did as a boy.

New York City was Jerry Herman’s home in the years when his name sold tickets at the box-office. And for a while, in the 1960s and ‘70s, and early ‘80s, he seemed to have the golden touch. (He took pride in the fact that Louis Armstrong’s recording of his song “Hello, Dolly!,” rose to the very top of the charts, knocking the Beatles out of the number-one spot. )

Then tastes changed; attention focused more on newer, younger theater writers with rock-inflected scores; and some of the critics began referring to Herman as old-fashioned or old-school; he felt rejected. It pained him that some younger musical-theater writers, as well as reviewers, spoke of him as if he were passé. I loved his work. I felt he still had a lot to contribute. And I would encourage him to write another show. He’d say, with a certain degree of sadness and wistfulness, it was too late for that. He told me: “At my age, I don’t think I could bear to have a flop.”

He remembered–with painful clarity–projects of his that had not been commercial successes. His first Broadway show, “Milk and Honey” (1961), was a success, running over a year; it put him on the map. However, the next Jerry Herman musical, “Madame Aphrodite,” which opened later in 1961 Off-Broadway (not on Broadway), was a real flop, running for only 13 performances. The New York Times panned the show overall, but added: “the score as a whole has a nice quality, and is further evidence that Mr. Herman will be heard from again.” “Madame Aphrodite” has never been revived anywhere since its first production. (Herman did not feel the show was worthy of being revived, and did not want it published or presented anywhere, even on an amateur level.) No cast album was ever recorded.

But Herman believed some of the songs in that score were first-rate, and he successfully reworked them for subsequent shows. For example, his song “Only Love,” outfitted with new lyrics, became the unforgettable “It’s Today” in Herman’s hit 1966 musical, “Mame.” (He said he got the idea for the new lyrics from his mother, who had once thrown a party with no excuse other than “It’s today!”) Another number from “Madame Aphrodite,” “Gotta Be a Dream”–with new lyrics–became “Love is only Love,” which Barbra Streisand eventually introduced in the film version of “Hello, Dolly!” (1969). Herman reused the melody from still another number in his “Madame Aphrodite” score, “Beautiful,” to create “A Little More Mascara” in his Broadway hit “La Cage aux Folles” (1983).

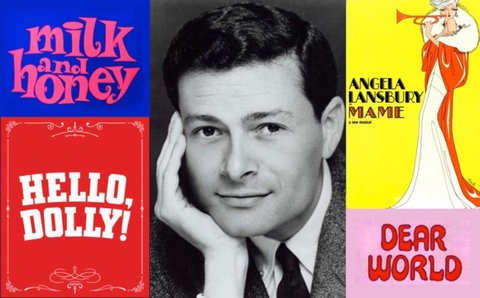

Jerry Herman with his show logos

Herman’s three biggest hits–“Hello, Dolly!,” “Mame,” and “La Cage Aux Folles”–were such great successes, running for so long, and then revived–that at one point he had all three of his musicals running at once on Broadway. But some of his other shows lost money. And in 1985, he was diagnosed as HIV-positive; he wondered how long he might live. For a while, he withdrew from show business. It was almost as if he’d retired, without announcing it. He concentrated on things like decorating his own home (and homes of some friends), and writing his memoirs.

* * *

He moved to California and then Florida. From time to time–even in recent years–he considered moving back to New York City, but concluded with a bit of sadness “My New York–the New York I fell in love with–is gone.” He sometimes spoke with me as if his time had passed.

But his music–written from the heart–continues to reach people. Seeing Betty Buckley brilliantly shining in Herman’s “Hello, Dolly!” was, for me, a huge high point of this year.

And I think we’re long overdue for a major Broadway revival of Herman’s equally spirit-lifting “Mame.”

Herman’s music–buoyant and big-hearted–was easy to love. And it reflected his own personality. And, oh! No one loved musicals more than he did. He could speak with me—with boundless enthusiasm–of, say, Alice Faye film musicals he loved as a young kid. And he could wax eloquent about songwriters of earlier eras whom he appreciated, like Irving Berlin, Cole Porter, the Gershwins. Rock music wasn’t his thing. It did not interest him. He did not want to try writing in that vein. He knew where his strengths were.

Jerry Herman with Carol Channing and Lee Roy Reams

The scores of all of his musicals–even shows that were not box-office hits, like “Mack and Mabel” and “Dear World’–offer an abundance of riches. He told me that “Mack and Mabel” was his own favorite score, out of all the scores he had written. (The show flopped due to book problems.)

He told me that one big regret in his life is that Judy Garland was never able to star in “Mame” on stage. She wanted to do it, and he’d always hoped she could do it. (He’d conceived “If He Walked into My life” as “a Garland song,” he told me. And if you listen to it, you can hear it.)

In 1968, Garland even auditioned for it, hoping to take over the role when Angela Lansbury left the show. (The audition took place at her townhouse on East 63rd Street in New York.) But the producers felt Garland was too risky, too unreliable. They doubted she’d have the discipline to do a Broadway show eight times a week. She’d given many dazzling concerts in her career. But she’d also failed to go on, on enough occasions, for the money men to be worried . The producers also felt she was so strong a personality, audiences would only be seeing Garland–not “Mame Dennis”–on that stage, and would probably be shouting “We love you, Judy,” and “Sing ‘Over the Rainbow.’” Jerry Herman told me, “Had Judy done the show for even a single performance and then quit, I would have been thrilled.” He was certain she would have been a terrific “Mame.” And he just wished she could have played the role somewhere–on Broadway or on screen, anywhere. But it was not to be. And she died the following year.

I liked Jerry Herman. I liked the man; he was endearing. And I liked his music. And he was one of the Broadway greats. Some of his songs–like some of Irving Berlin’s–are so simple, direct, and accessible–that sophisticates sometimes failed to appreciate them. But he spoke to the heart. And reached audiences well. He made Broadway a brighter place. Audiences left theaters humming his songs.

I will miss him. I am glad there are people like Michael Feinstein keeping his music alive. I was glad I got to hear Feinstein sing Herman’s words: “As long as you love one another, you’ll have the best Christmas of all.” That made Christmas-time a little nicer for me this year.

Broadway will dim its lights for Jerry Herman on January 7th, 2020.

* * *

I enjoyed Michael Feinstein’s show a lot. Oh, he probably had me on the first number. Maybe even before the first number; I was beaming just in anticipation, when his musicians took the stage.

It’s hard for me to be objective about Michael Feinstein. When I see him on stage, it’s almost like seeing an old friend from high school. To me, he never changes. He’s still that good-looking, enthusiastic young man who loves the old songs. And he has a rare gift for making everyone share his love. I “got” him when he first emerged on the scene. And I still “get” him the same way.

I won’t look up how old he is now or exactly when he broke through as a performer. To me, it feels like a moment ago when he arrived on the scene. I’m a bit older than him and remember the delight I felt when this fresh young singer appeared, singing timeless old songs that were well-known, along with fascinating vintage rarities and rediscoveries that almost no one else knew–and somehow making them all appeal to most anyone who heard him in the clubs. And he’s still doing it.

But I do know this. When I first started writing for the New York Post, Michael Feinstein had not yet released his first album. His breakout engagement at the Algonquin Oak Room in New York won him loyal fans. He began releasing albums, singing songs written well before he was born. And the albums did well. He recorded salutes to master songwriters–often including “unknown” songs, as well as standards. He didn’t compromise or make concessions to try to win over younger listeners. He stayed true to himself, and he drew listeners to him.

I marveled at all of that. I would scarcely have thought it possible; I admired what he did; I would never have guessed it would be commercially viable. But he succeeded in a big way, artistically and commercially. He contributed to a resurgence of interest in the Great American Standard. He helped revive and revitalize the cabaret scene as a performer. And for the past two decades or so, he’s also made an important contribution, running clubs bearing his name. And his albums have sold exceptionally well.

I’d encourage any aspiring cabaret performer to study his shows. For he knows about as well as anyone working today how to structure an act, how to pace it well, how to mix slow songs and fast songs, and how to set up songs–saying just the right things to help the audience to fully appreciate the songs. And how to make the whole thing gradually build. He does it so deftly, it all seems natural. But it’s harder than it looks. (The cabaret world, alas, includes a goodly number of performers with good pipes who don’t know how to offer good shows.)

Michael Feinstein in performance at 54 Below

He opened with a bright medley of Alberta Hunter’s “My Castle’s Rockin’” and Fats Waller’s “The Joint is Jumping.” A lively opener, to let the audience know they’re in for a good time.

Then he slowed things down with three sentimental 1940s ballads composed by Harry Warren: “I Know Why”/”The More I See You”/”There Will Never be Another You.” Nostalgia for the oldest members of the audience. But Feinstein draws a diverse audience. And he spoke enough about Harry Warren (and his own personal connection to Warren) so that audience members too young to know these songs or know the name “Harry Warren” would care, too. I looked around. It was clear that the young couple to the right of me were enjoying it, no less than the older folk sitting behind me.

He romped through “There’ll be Some Changes Made” (a big hit of 1921), and I enjoyed every moment of it. Then offered us more contemporary ballads, like Burt Bacharach & Hal David’s “(They Long to Be) Close to You” (from 1970) and Carole King & Gerry Goffin’s “Will You Still Love Me Tomorrow?” (from 1961). And sang them with such sincerity and conviction, he put them over as effectively as the classic older pop songs he’s best known for.

And oh! It was such great fun singing along with Michael Feinstein on Tom Lehrer’s “Hanukkah in Santa Monica.” We were all laughing and singing, and clapping. Feinstein pulled us all into the show, 100%. It’s a funny song, and Feinstein always makes it work. And singing with him made the bond between performer and audience even stronger.

I was having such a good time, I could have gone home right after that number and felt satisfied. I mean, it was wonderful being able to sit it in this posh nightclub, and enjoy a gifted entertainer offering numbers celebrating Christmas and Hanukkah. A perfect New York experience.

But the best was yet to come.

Feinstein went into a medley of songs made famous by Fred Astaire. And this was sheer perfection. The songs, the singer, the accompaniment, the stories. Fred Astaire is Feinstein’s favorite singer, the medley included ever-fresh songs by the Gershwins, and Feinstein’s anecdotes made us share in his love for Astaire, the Gershwins, the songs.

And these still-modern-sounding Gershwin songs–like “A Foggy Day,” “Let’s Call the Whole thing Off,” “Oh, Lady Be Good,” and “He Loves and She Loves”–are among the greatest popular songs ever written. And he “gets” them. He gets their rhythm, their sensibility, their humanity.

Some years back, I made the mistake of inviting a young singer, then attending AMDA, to a concert by Feinstein. Afterwards the singer told me: “Why did you take me to see him? I’m a better singer than he is. There’s nothing he can do that I can’t do.” The young singer’s technical skills were indeed excellent; he was blessed with a full, rich voice. But he sang every number in his repertoire the same way–“all out” with a big finish, as if he were trying to thrill the audience on “American Idol.” I had hoped he might learn something from watching Feinstein–that you need to know when to really sell a song and when understatement actually works better instead; when you need to be powerful; and when you need to try a lighter touch; and when you need to just sort of step out of the way and let the song itself–sung with complete respect for the songwriter’s intentions–tell its own story. Feinstein understands those things.

I savored that Astaire medley. And the knowing way that Feinstein wove his way through it. And I thought of my young friend with the full rich voice who would not know what to do with a song as jaunty and graceful and subtle as “He Loves and She Loves.” The Astaire medley was Feinstein at his best. And his commentary was not only informative, it was touching. (Feinstein can, through sheer earnestness, make almost any song work. I could appreciate his 1970’s ballad medley–but I didn’t necessarily believe every song in it was worthy of him. Every song in the Astaire medley, by contrast, was a gem, and it just suited him perfectly.)

I wasn’t sure anything could follow that Astaire medley. But I got a tremendous kick out of the next number Feinstein performed, Irving Berlin’s “Alexander’s Ragtime Band.” He gave it his own treatment, starting in an unexpectedly slow, sensuous manner, and then adding razzmatazz as he went along.

Now that number was written way back in 1911. (Feinstein noted, in an appealingly self-deprecating aside, “That shows you how au courant I am.”) And I’ve heard it performed a million times. But he made it feel brand new. And he engaged us. I don’t want to say exactly what year it was when I first heard Michael Feinstein perform that song–I’m afraid it might date me (even if it feels like just yesterday). But Ronald Reagan was then our President… and he still had a few years left to serve.

But it really was a joy to hear Feinstein’s version, and I’m glad he keeps it in his repertoire. (He should record it again; it’s a classic.) Berlin has always been a great favorite of mine. In fact, just two days before I saw Feinstein, I was singing Berlin songs with my friends outside of Berlin’s former home–a tradition that a friend of mine, John Wallowitch, started back when Berlin still alive. Feinstein also conjured up the ghost of Mr. Berlin (“Sing it! Sing it!”), urging Feinstein to give us “White Christmas” before the night’s end. And he did.

A terrific show.

– CHIP DEFFAA, January 3, 2020

Leave a comment