Remembering and Honoring Charles Dodsley Walker (1920-2015)

The memory of a remarkable organist and sacred music choral conductor continues to inspire.

[avatar user=”Jean Ballard Terepka” size=”thumbnail” align=”left” link=”file” target=”_blank”][/avatar]In the two months since Charles Dodsley Walker died peacefully in his ninety-fifth year, his remarkable life has been extolled in informal gatherings, in conversations and private ceremonies, in letters and emails and written tributes all over New York City, in the northeast and even far beyond. Walker lived so very long and so very productively that three full generations, perhaps even four, of musicians and music-lovers remember him. What’s particularly noteworthy is that the tone of affectionate respect and passionate admiration for Walker is equally happy among teenagers and young adults, men and women in busy middle age, and Walker’s friends, colleagues and contemporaries now themselves in their late seventies, eighties and early nineties.

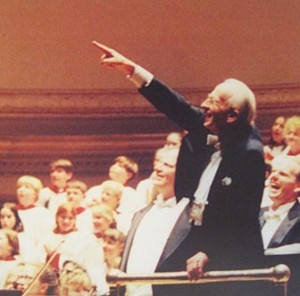

Walker remained professionally active until just a week before his death, still discussing particular pieces of music and conducting approaches with Jonathan De Vries, his chosen successor as conductor of the Canterbury Choral Society. In his final years, he concentrated on his work as a sacred music director and church musician. In addition to his position as Artist-in-Residence at St. Luke’s Parish in Darien, Connecticut, Walker remained music director and conductor of the Canterbury Choral Society, which he founded in 1952. In the last four seasons, Walker conducted performances – with full orchestra, children’s choirs and the Canterbury adult chorus of over 100 singers – of six centuries of works by Dufay, Schutz, Gabrieli, Purcell, Bach, Charpentier, Mozart, Berlioz, Verdi, Vaughan-Williams and Langlais – in addition to a dramatic and magnificent production of Gustav Mahler’s Eighth “Symphony for a Thousand” at Carnegie Hall, in January, 2013.

Walker’s superb musicianship as a choral conductor made him a prominent figure in the world of classical music. In 1982, Walker co-founded what was first called the Berkshire Choral Festival and was associated with it for eighteen years, including a full decade as its dean and music director. Upon his retirement, Berkshire Choral International established the Charles Dodsley Walker Award for excellence in choral conducting.

In addition, Walker led the Blue Hill Troupe, “New York City’s Musical Charity,” for thirty-five years, conducting all thirteen Gilbert and Sullivan operettas several times each. Walker captured perfectly the deft mixture of seriousness and wit, rigor and light-heartedness that this large repertoire demands.

As an educator, Walker was indefatigable. For twenty-four years, he chaired the Music Department at the Chapin School; during the summertime, he served as Organist at the Lake Delaware Boys’ Camp almost continuously from 1940 to 1990. In the weeks since his death, scores and scores of reminiscences, condolences and testimonials have poured in from former students to the institutions where he taught, to the public guest book of his New York Times-Legacy obituary (http://www.legacy.com/obituaries/nytimes/obituary.aspx?pid=173934942), and to his widow, describing Walker’s contributions to their lives. He taught them to love music. He also taught them moral integrity, personal decency and civic responsibility.

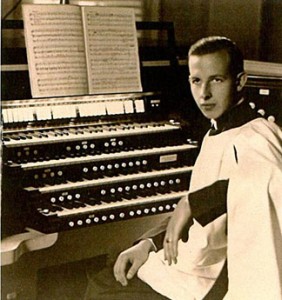

From 1951 to just seven years ago, Walker was one of the busiest full-time church musicians in the tri-state area, working first at the Church of the Heavenly Rest in Manhattan – for thirty-eight years – and then at Trinity Church in Southport, Connecticut, from 1988 to 2007. Under the auspices of New York University, C.U.N.Y. – Queens, Manhattan College of Music and Union Theological Seminary, he also taught organ for over forty years; organists all around the country now at the height of their careers still count Walker as a foundational teacher and major inspiration.

In the complex world of organ playing and organists, Walker was an influential leader for more than half of a century. He held virtually every major office in the American Guild of Organists from the 1950s on and helped to oversee the reorganization of its governance structure in the 1970s.

Hundreds and hundreds of colleagues and professional musicians over more than seventy-five years, thousands of students, and still other thousands of church choir and Canterbury Choral Society singers were influenced by Charles Dodsley Walker.

As a little boy, Charlie Walker was brainy and earnest. He liked math and science and working with his hands, and was very good at all of them. He enjoyed the outdoors and was energetic. From early adolescence on, he was gregarious and considerate, and he never ever forgot a friendship.

As a little boy, Charlie Walker was brainy and earnest. He liked math and science and working with his hands, and was very good at all of them. He enjoyed the outdoors and was energetic. From early adolescence on, he was gregarious and considerate, and he never ever forgot a friendship.

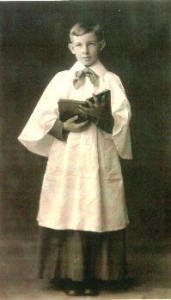

He also, early on, dearly and deeply loved music and felt a profound affinity for it. His parents – and his brothers, too – recognized his musical talent when he was a youngster, although the depth and breadth of his gifts would not become clear to them for many years. The Walkers had a piano at home – singing of all different sorts had always been part of the Walkers’ convivial family life – and after Charlie taught himself to play all the hymns in the Episcopal hymn book, when his feet could barely reach the piano pedals, his parents enrolled him in the Cathedral School of the Cathedral of St. John the Divine. He began singing in the Cathedral choir as a soprano, and studying voice and organ.

Walker decided to be a church musician when he was ten; he never deviated from that decision.

Though other spheres of musical activity additionally claimed his prodigious energies, sacred music was always at the central core of things. And he was superb at it.

But in all the recent accolades for Walker’s musical achievements and professional successes, two additional interconnected features of his life have been under-reported and deserve recognition.

Walker’s story is a quintessentially New York City story. Connecticut figures in periodically: Walker went to Trinity College, graduating in 1940, and had his first and last church jobs there. Massachusetts does, too: he studied at both the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Harvard, from which he received his Master of Arts degree in 1947, and he spent many summers in the Berkshires. And Paris … and Europe. Immediately at the end of his World War II military service – his final rank was Lieutenant Commander in the United States Navy – he was called to be organist at the American Cathedral in Paris, where he met and married his first wife, soprano Janet Hayes Walker, with whom he toured and concertized all over the continent; later, after his first wife’s death, he traveled annually all over Europe with his second wife, Lise Phillips Walker, enjoying fine cuisine and beautiful sights, and contentedly, energetically visiting as many important composers’ homes and habitats as possible.

But New York City was his personal and musical home, from his boyhood experience of singing – Bach, whom he particularly loved, and the full Anglican sacred and liturgical repertoire – at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine starting in 1930 to the last Canterbury concerts he conducted – Bach, Haydn and Mozart – at the Church of the Heavenly Rest in 2014. New York City was the center from which Walker’s musical life radiated and to which it returned.

But New York City was his personal and musical home, from his boyhood experience of singing – Bach, whom he particularly loved, and the full Anglican sacred and liturgical repertoire – at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine starting in 1930 to the last Canterbury concerts he conducted – Bach, Haydn and Mozart – at the Church of the Heavenly Rest in 2014. New York City was the center from which Walker’s musical life radiated and to which it returned.

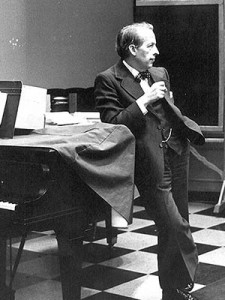

And New York City provided the geography for Walker’s most unheralded and, in some ways, most important accomplishment: he was a living exemplar of a successful career in music. His life itself was testament to the ways in which a productive career in music supports other musicians and creative artists. It provided a model for students and adults: a life in music can be as productive, engaged, intelligent and intelligible as all sorts of other lives … in law or medicine, accounting or architecture, civil service, sales, diplomacy, social work, or all the various other fields of his secondary school students’ parents, and of volunteer adult choristers, and their friends and spouses. Above all, Walker’s professional life of music-making contributed to the health, sanity and vitality of thousands of people’s lives.

Walker was a musician whom other musicians were grateful for: it mattered to them that his support of others’ endeavors, projects, plans and goals was unwavering and that he praised colleagues’ successes. Working with professional singers and instrumentalists, he was always solicitous of their needs. In full orchestra rehearsals, he started on time and ended on time, adhering with reliable common sense to union rules. Walker was constantly alert to the demands of musicians’ frequently shape-shifting careers: he knew that any single professional musician he worked with might be juggling two or three jobs, so he’d adjust rehearsal schedules to accommodate people’s needs to get to their next gigs – in Broadway or ballet or opera orchestra pits, in dinner theaters, classrooms, recording studios or choir lofts – in good time.

Walker recognized that talented singers come from all kinds of places: soloists who sang with Canterbury over the years came from opera, Broadway, off-Broadway, churches and synagogues, colleges, universities and conservatories, and musical theater. One singer who has performed with Canterbury for many years as a section leader and a soloist had, until relatively recently, a thriving career on cruise ships all over the world. Walker was as eager to work with young musicians – singers and instrumentalists – as a mentor and teacher as with established, mature professionals. He treated rehearsal accompanists as partners, featuring them in concerts he conducted and encouraging them in the development of their independent careers.

Walker embraced radio and television with zest and glee for performances and discussions of music; he was interested in the actual process of making LP records and then CDs, looked on recording engineers as colleagues, and eagerly kept up with developments in music-related computer software, technology and electroacoustics. He understood not just instrumentalists but their instruments; his orchestra rehearsals were models of attentiveness to the needs – and particular strengths – of each section and individual section leaders.

His expectation of the highest possible musical standards in everyone with whom he worked was a matter of patient and explicit discipline, cheerful, clear and useful direction, and sturdy, unsentimental optimism.

As an administrator, Walker made every project, production, liturgy and church service, concert and concert season operate like the proverbial well-oiled machine. As director and conductor of the Canterbury Choral Society from 1952 on, Walker negotiated contracts for orchestras and soloists, rehearsal spaces and concert halls; he worked collaboratively with a busy board of trustees on practical 501(c)(3) logistical and even legal procedures, fund-raising, and skilled, realistic budget management. He oversaw thirty to forty Canterbury rehearsals a year, and planned and mounted three major concerts a season. Every year. For sixty-three years.

As an administrator, Walker made every project, production, liturgy and church service, concert and concert season operate like the proverbial well-oiled machine. As director and conductor of the Canterbury Choral Society from 1952 on, Walker negotiated contracts for orchestras and soloists, rehearsal spaces and concert halls; he worked collaboratively with a busy board of trustees on practical 501(c)(3) logistical and even legal procedures, fund-raising, and skilled, realistic budget management. He oversaw thirty to forty Canterbury rehearsals a year, and planned and mounted three major concerts a season. Every year. For sixty-three years.

Stationers and printers, post office employees, concert site managers and maintenance staff, secretaries and executives’ assistants, sextons and vergers all found Walker reliably easy to work with. His promptness, politeness and low-keyed straight-forwardness mysteriously embodied a certain kind of old-fashioned, gentlemanly, no-nonsense professionalism that many people sensed was fading away.

Walker never pretended that a career in music was an easy career, but he was always delighted to discuss it with anyone who asked. And he was always encouraging. “A career as a musician?” he would say in conversation with friends … or friends’ children. “Well, of course” – looking a person straight in the eye – “If you’re very talented and you work very hard, it can be a wonderful career.”

Walker was a successful professional musician for three quarters of a century. He was a church musician and a sacred choral music conductor primarily, but his career connected with careers of musicians from all fields. He respected and valued competent musicians in absolutely any field and did everything he could in his own career to support theirs. Church music is a small, discrete and awfully idiosyncratic pocket of the musical world. Walker was among the best of the best in this world. But, in fact, he moved in a wide variety of divergent musical circles while always revealing and facilitating their human and artistic interconnectedness.

The little boy who at ten knew he wanted to be a church musician grew up to be, more than eighty years later, a spry, wise man whose endlessly productive, generous and multifaceted musical career inspired thousands and thousands of people in the big city he lived in and loved.

This is indeed a man to be remembered and honored.

A memorial service and celebration of Walker’s life open to the public will take place at the Church of the Heavenly Rest, 2 East 90th Street in Manhattan on Saturday, March 21, 2015 at 3:00 p.m. For more information, call 212-222-9458 or visit http://www.canterburychoral.org or http://www.heavenlyrest.org.

Hi. Just learned about my mentors passing! Little Kathy Griffin always showed up for choir rehearsal. It was a “ thing” to allow me to join choir. Back in the day, it was all about if I could READ. Yes, I could in 1st grade and Mr Walker encouraged me, taught me,, made us all feel So Special! Crosses with special colored ribbons!

He was pretty tolerant back in the ‘ 6O’s with we choir girl! We slipped candy between the pages of our hymnals, bu were forgiven as we sang beautifully

I was in the boys choir at the Church of the Heavenly Rest for several years, from 1954 to 1958. Open your mouth like an Edsel, he used to say. Even now, 70 years later, I think about him often. He was funny and so very talented. His life and career was full of elegant energy.

You did not mention that for many years he was the music teacher and organist at the Kew Forest School in Queens where he had a tremendous influence on my life!

Mr Walker was an amazing human being and an amazing Choir Conductor, and Great Musician/ Organist.

I sang with him as an Alto section Leader in the Trinity Episcopal Church in Southport, CT, where we has the Music Director/ Organist and Choir Conductor. We had wonderful years singing great pieces of great composers in concerts , oratorios at the church in Connecticut and New York with Canterbury Choir Society . We did sing twice at the Carnegie Hall which was an amazing experience. We did Bruckner’s Noye’s Fludde Opera at the Trinity Episcopal Episcopal Church which was an amazing and grandiose event. I really miss those times. Mr Walker will be always in everyone’s memory as the nicest person, amazing musician and wonderful friend. He will never be forgotten.

I just saw Mr. Walker as a contestant on an old To Tell The Truth episode from the 60’s . When he said his real name and occupation I had to look him up. God rest his soul and thanks to his service to Our Lord