On the Town with Chip Deffaa at Anthony Rapp’s “Without You”

In "Without You," Anthony Rapp performs Jonathan Larson songs with a sense of complete authority and ownership. He gives an utterly satisfying performance. This is Rapp’s best showcase since Rent. And the best one-man show I’ve seen in years.

Anthony Rapp in “Rent”

[avatar user=”Chip DeFFaa” size=”96″ align=”left”] Chip DeFFaa, Editor-at-Large[/avatar]

Carol Channing used to tell me: “An actor is lucky if he or she gets one great role in his career, one that really lets the audience see what the actor is capable of. I was one of the unusually lucky ones. I got two such roles in my career.”

Anthony Rapp now joins that small group of what Carol Channing would have termed “unusually lucky” actors–he has now gotten two great roles. The first, of course, is that of “Mark Cohen” in Rent. He originated that leading role, played it on stage in New York, in London, and on tour, and reprised it in the motion-picture adaptation of Rent.

I’ve seen Rent–in all sorts of productions in all sorts of places–countless times. I’ve never seen anyone play the role of “Mark Cohen” with more conviction than Rapp; he owns that role. And when I see regional productions of Rent, it’s often obvious that the actor playing “Mark Cohen” has listened many times to Rapp’s performance on the original cast album of Rent, because he’s copied Rapp’s choices as to phrasing, inflection, emphasis, tone.

I’ve always appreciated Rapp’s skills. Over the years, I’ve enjoyed seeing Rapp play assorted different characters on stage (in such shows as You’re a Good Man, Charlie Brown and If/Then), on screen (including A Beautiful Mind, Twister, Six Degrees of Separation), and on TV (Law and Order: Psych, SVU, Star Trek: Discovery). But none of those various other productions, as agreeable as they may have been to watch, have showcased his particular strengths nearly as well or as completely as Rent did.

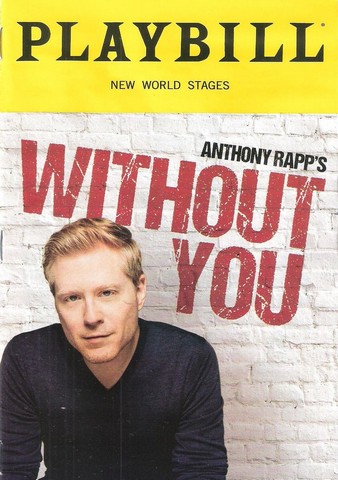

“Without You” Playbill from New York Stages

But now Rapp is starring Off-Broadway at New World Stages (340 W. 50th Street, NYC) in an autobiographical one-man show that he has written, Without You. And he has created the best showcase for himself since Rent. The show is well-written and well-directed. And it is brilliantly performed. Without You is the best one-man show that I have seen anywhere in years. And that is saying plenty.

Based on his acclaimed memoir of the same name, Rapp’s show tells of how, beginning in 1995 (when he was an out-of-work actor working at a Starbucks to survive), he auditioned for the rock opera that would forever change his life: Jonathan Larson’s trailblazing Rent. And while Rapp is getting the biggest break of his career, starring in a landmark musical—the most impactful musical in many years, a once-in-a-generation kind pf phenomenon—he is simultaneously dealing with the losses of both his mother and of Larson. And Without You—like Rent itself –becomes an affirmation of life in the midst of tragedy, and a poignant reminder to make the very most of whatever time we may have.

Rapp’s show—directed by Steve Maler, with musical direction/orchestrations by Daniel A. Weiss (who was the associate conductor/second keyboards player of the original Broadway production of Rent)—is quite moving. I was held by it throughout. And it is extraordinarily rich with Jonathan Larson songs, including “No Day but Today,” “We’re Dying in America,” “Rent,” “La Vie Boheme,” “One Song Glory,” “Seasons of Love,” “Without You.” Hearing these familiar songs—which I’ve heard so many times in Rent, performed by multiple singers—in new contexts, now sung solo—gives me an even greater admiration for them. They are such well-crafted songs, and they have enormous impact here, just as they did in their original contexts.

Anthony Rapp in “Without You” at New World Stages (Photo credit: Russ Rowland)

Rapp has an especial affinity for Larson’s work; no one performs Larson’s songs more compellingly. He has long been the foremost interpreter of Larson’s music. He “gets” the music completely. It resonates for him. No one interprets Larson’s work better.

I’d like to add, as a kind of sidebar, that I saw Rent repeatedly over the years throughout its long run in New York. I took practically every friend and relative and colleague I knew—even my agent—to see it. Many loved it; some hated it. I found Rent to be a unique and powerful show, with a spiritual quality that just got to me.

It distressed me to see the long-running New York production of Rent gradually get weaker over time, with performances by various replacement-cast members and understudies eventually taking on a “we’re just-going-through-the-motions-now” kind of quality. I hated seeing such a great show being performed with such indifference—but that can sometimes happen to any show that’s been running for years and years.

Then Rapp rejoined the New York production of Rent. He once again took over the role of “Mark Cohen” that he’d originated years before, and his impact upon the whole production was galvanic. His performance was so sincere and true that everyone else in the cast was forced to give their best as well, to rise to the occasion. It was as if he’d given some kind of a blood transfusion to the whole cast. The production, to my very happy surprise, suddenly felt almost like Rent had felt when it was brand new. Rapp cared so much about the show. And now everyone else seemed to care more, as well. I never saw a situation quite like that, before or since then, in the theater, where one cast member could make such a difference. But I watched Rapp give 100%, night after night in Rent, and others on stage were forced to step up their game.

Anthony Rapp in “Without You” at New World Stages (Photo credit; Russ Rowland)

In Without You, Rapp performs Jonathan Larson songs with a sense of complete authority that is rare to encounter anywhere, and is utterly satisfying. The score to Without You, I might add, does not consist only of Larson songs. (To give just one example, it is interesting to hear Rapp zestfully perform “Losing My Religion”—a big hit for R.E.M. in 1991–as his audition song for Rent; Rapp makes us feel like we’re right there with young Rapp at that hope-filled audition.) But it is the Larson songs that provide the backbone for the show. They are all strong, well-chosen, well-positioned, and impactful. Wisely, Rapp did not include some Larson songs, like “Tango Maureen,” that only work meaningfully within the context of Rent.

Rapp is now 51. He was 24 when he first sang some of these Larson songs. He’s singing them even better now. And the arrangements are terrific. (The reflective contributions of Clerida Eltime on cello add considerable beauty.) I hope Rapp gets to record a cast album. I hope the producers of this Off-Broadway show will get offers from record companies. Heck! I’d produce such an album myself if no one else wanted to. It’d be the strongest representation yet on disc of Rapp’s work, and a most welcome addition to the Larson canon. I’m actually surprised there is not a cast recording for sale now; people attending the show would be buying it. And potential sales are being lost with each day’s delay.

When I wrote and directed George M. Cohan Tonight! at the Irish Repertory Theater, Ghostlight Records/Sh-K-Boom—which produced the original cast album of my show–made sure that some copies of the cast album were available for sale in the lobby from the very first performance; they understood that there are no more motivated buyers of cast albums than people who’ve just seen the show itself. And Ghostlight/Sh-K-Boom rushed the production process to make sure that at least a bare-bones album was available for sale by Day One, even if the copies offered for sale in the first week or two lacked the liner-notes I’d written, since the liner-notes booklet was still being printed. But at least we had an album for sale, for impulse-buyers who’d just enjoyed seeing the show. Getting a Without You cast album out should be a high priority.

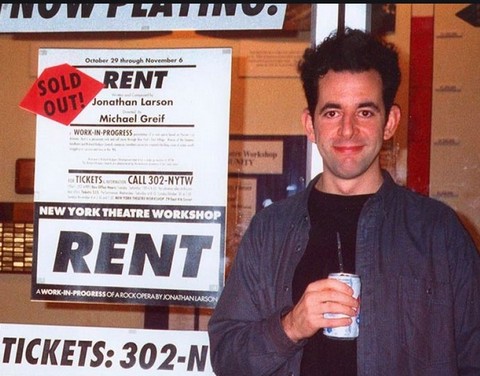

Jonathan Larson in front of “Rent” poster at New York Theatre Workshop

Without You showcases Rapp well as an actor, not just a singer. In Without You, as Rapp recalls people he encountered, he really brings them to life for us. He evokes them vividly. He makes us feel his mother’s presence, as she shares her awareness of how seriously ill she is. And he makes us feel Jonathan Larson’s quirky but confident presence—the starving artist who hoped he represented the future of musical theater. He gives us Jonathan’s self-effacing father, Allan Larson, to a tee. Rapp conjures up the sweet/sad sound of Allan Larson’s voice, and his soft-spoken but determined manner of speaking. (I met Allan Larson at various occasions, including recording sessions and performances of Rent; and he came to a little concert I presented in tribute to Jonathan Larson, after Jonathan’s passing. And we spoke on the phone.) I liked hearing each of the different characters we meet “speak” through Rapp in this one-man show.

Rapp gives an engrossing performance in Without You. It brought back lots of personal memories for me, too, because I recall so well the emergence of Rent. Friends of mine were working with Jonathan Larson while he was developing Rent; they helped him do readings and make emo recordings. Larson devoted seven long years to the creation of Rent. I was hearing of its promise and its power from friends who were working with Jonathan—then a largely unknown artist–well before the show took final form. I got to meet various cast members when the original Off-Broadway production was cast. When performances began at the New York Theatre Workshop, I sat with a friend of mine who had been in an earlier reading of Rent, and was as eager as any of us to see how the work had evolved.

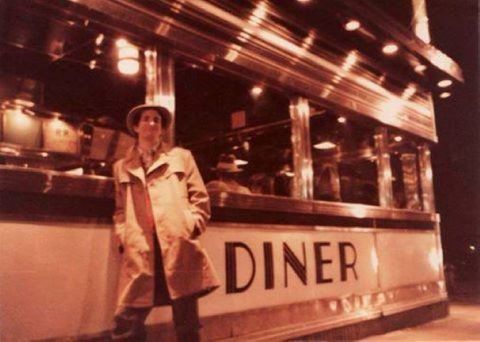

Jonathan Larson at the Moondance Diner, New York City

Jonathan Larson was a struggling artist when he was writing Rent. For most of that period, he was working as a waiter at the Moondance diner; that was his survival job. (He even helped write the diner’s “Employee Manual.”) Few people outside of really hardcore members of the theater community knew Jonathan Larson’s name then. But he had some fierce believers in him. People who saw and heard something special in his work. Like the friends who volunteered to make demo recordings of his songs for free. Or championed him to those who listened.

In this time period, I was writing about music and theater for The New York Post and for Entertainment Weekly, and I was blessed to work with some unusually enlightened and generous editors, who let me cover pretty much anything I thought was worth covering. Their philosophy was: “You’re the expert here; you know more about music and theater than we do; if there’s anything you really want to write about, write about it! Just follow your instincts.” I got to spill ink on up-and-coming artists, from Norah Jones to Harry Connick, to Peter Cincotti, before they’d released their first albums or had gotten any real press, simply because I believed in them.

At the start of the 1995-96 theatrical season, the prevailing opinion in the theater world was that the most highly anticipated, most important, and most-likely-to-succeed theatrical production was going to be the Broadway musical Big. This new stage adaptation of the smash hit movie Big had the biggest budget of any Broadway show up until that point. The best publicists in New York were working full-blast to make sure that every editor, publisher, reviewer, columnist, features-writer, and potential influencer of any kind knew that Big was coming, and that it required maximum coverage. The advance publicity for Rent, by contrast, was exceedingly modest, polite, gentle, low-key. The publicist reminded us that Larson was a young writer whose work had previously been presented courtesy of the Naked Angels Theatre Company, the American Musical Theatre Festival, and Broadway Arts, among others; and that Larson’s next project, following this limited-engagement presentation of Rent, would be a new musical he was working on for the “Adirondack Theatre Festival.” (I remember wondering: What in the world is the Adirondack Theatre Festival, and what is he working on to present there?)

The average person has no idea of how much media coverage any show or individual might get is determined by publicists. A big-budgeted show like Big, hiring a top PR firm, could aggressively blitz the media with multiple press releases and phone calls and faxes and messages, and generate lots of advance hype. A small Off-Broadway production by a non-commercial theater company like the New York Theatre Workshop, operating on a very modest budget, can’t afford to spend nearly as much on PR and marketing. And at the start of the 1995-96 season, there were not too many writers, editors, or publishers who even knew who Jonathan Larson was, or thought the Off-Broadway offerings of the New York Theatre Workshop were particularly newsworthy. The accepted wisdom was that Big—which was set to open at one of Broadway’s most prestigious and desirable houses, the Shubert Theatre (where A Chorus Line had played for a record-settting 15 years), following a costly, extended out-of-town tryout in Detroit—was to be the most important theater-opening of the season. A lot of editors simply take their cues from what publicists convince them is worth covering,

My editor at Entertainment Weekly said he was going to send me to Detroit so I could see the out-of-town tryout of Big right from the start, meet cast members, do interviews, and begin coverage of this blockbuster musical as it started its trek to Broadway. I thought that could be fun—I always welcomed out-of-town trips–but I wanted to discuss options more with my editor. Because, despite all of the drum-beating by top publicists for Big, I knew some people working on the production who’d suggested to me off-the record that there were problems with it. And I also knew some people working on Jonathan Larson’s Rent—people I trusted—who were convinced that Jonathan had something important to say, and was bringing something new to the stage. Something that caught the present moment better than any show in town did. And they hoped that their little Off-Broadway production would get some coverage, too.

I told my editor I’d be more interested in covering Rent rather than Big. And even though Rent was being mounted on a budget that was but a teeny fraction of the budget for Big, I had a hunch it might be the more significant work. And my editor, who trusted my judgement—and was hip enough to be familiar with Jonathan Larson’s work, which very few people even knew about back then—said we’d scrap my planned trip to Detroit to cover Big from its start, so that I could stay in NYC instead and document the emergence of Jonathan Larson’s Rent. A well-informed colleague at the New York Times was similarly given a green light to cover Larson, whose work he appreciated, and Rent. We had a jump on most other publications because we happened to know some of Jonathan Larson’s work and were convinced—even if Larson had not yet achieved any commercial success or fame—that the show he’d spent seven years creating deserved some attention. Even if it was just a limited run at a nice little theater that didn’t tend to present commercially successful works.

Maybe we were rooting for the underdog a little bit. But I knew that Larson had devoted years of his life—with little reason to expect any real financial reward—to developing a show that he was passionate about. I tend to like true believers in the work they’re doing. And I suspected the producers of the Broadway musical version of Big may have put up their millions of dollars simply because the original movie had made so many millions that they were confident any halfway decent stage version of it would likely bring in many more millions. And I’m generally more curious to see what a real artist, willing to sacrifice all to develop art for its own sake, can come up with, than to see stage adaptations of commercially popular films–which all too often turn out to feel uninspired.

One thing that none of us could have foreseen, of course, was that, just before the first public performance of Rent, Jonathan Larson would die of an aortic dissection; he was only 35. He’d been suffering from chest pains, dizziness, and shortness of breath for several days before his death. Doctors at two hospitals had told him it was probably just stress or the flu, nothing to worry about. He died at home in the early morning of January 25, 1996, the day of the first Off-Broadway preview performance of Rent. His body was found on the kitchen floor by his roommate at 3AM. (His parents would later successfully sue the two hospitals that he’d gone to, for malpractice.)

I remember these startling, unexpected events as if they happened yesterday. And I also remember the extraordinary energy that the cast gave off, presenting Rent at the New York Theatre Workshop. That little theater seemed like it was about to explode. That was one of the most exciting nights in my theater-going career. Everyone in the cast was giving everything they possibly could, honoring Jonathan’s memory. The audience did not want to let the cast go at night’s end. I felt I’d witnessed as strong an ensemble performance of a show as I’d ever seen, anywhere, any time. (The original cast of A Chorus Line—a very different show but also presented with great conviction–also had a remarkable ensemble energy.) And the cast members of Rent were, by and large, “unknowns,” working for peanuts in a small, non-commercial theater. The audience’s applause was thunderous. And Anthony Rapp lifted his hands and clapped three times for the spirit of Jonathan Larson–a respectful, appreciative gesture that he was to repeat in the curtain calls night after night throughout his years of association with Rent.

The 15 actors on stage at the New York Theatre Workshop were launching what turned out to be the most important theatrical production of the season—and much more than just that season, as it turned out. The ponderous, poorly paced, overproduced Broadway musical adaptation of Big–which retained the plot of the film Big but somehow failed to capture any of the film’s beauty, grace, whimsy, or magic–came and went quickly, soon to be forgotten. Rent transferred from Off-Broadway to Broadway, and went on to win multiple Tony Awards, plus the Pulitzer Prize. It became the 11th longest-running show in Broadway history. It’s had numerous international productions, a film adaptation, a “live” television presentation, and much more. Since his passing, Jonathan Larson’s sister, Julie Larson, and his former girlfriend/best friend/original champion, Victoria Leacock Hoffman, have worked tirelessly to keep his legacy alive.

Anthony Rapp in “Without You” at the New World Stages (Photo credit: Russ Rowland)

Rapp’s one-man show takes us through the essence of Jonathan Larson’s story in taut, economically written language. And it also lets us share in Rapp’s experiences with his mother, and with others important to him. We feel like we’re there as it all happens. And we share in the emotions. Rapp knows when understatement rather than sensationalism packs the strongest punch. And when he mentions to us that Larson has unexpectedly fainted during one rehearsal of Rent, the incident is casually related in a very matter-of-fact way; no one, at the time, wanted to imagine that Jonathan’s fainting might actually be a foreshadowing of a grave problem. (As it was.) And yet Larson’s music is informed by a certain haunting urgency—that’s part of what gives it its power—as if he knew, on some subconscious level, his time was limited.

Rapp’s show is powerful. As Rent was–and is. I remember the excitement I felt, writing about Rent for Entertainment Weekly; I wanted so badly to help spread the word that this show in a small Off-Broadway theater, created by a poor–and still basically unknown–writer, who’d lived for years in a New York City apartment without any heat, was a must-see. And the show was so different from anything else playing in New York at the time, it felt revolutionary.

My editor at Entertainment Weekly ran almost everything that I quickly wrote about Rent unchanged; he was fine with me praising the book, the music, the performances. But he cut a couple of lines I wrote praising the trailblazing way Larson treated same-sex love as exactly the same as heterosexual love, showing us natural displays of affection—like kisses between members of the same sex—with a welcome and long overdue casualness. The editor worried that my praise for Larson’s depiction of same-sex love might be going too far for some readers, and cut my reference to same-sex kissing. Out of all of the zillions of pieces that I’ve written over the years relating to theater, that was the only significant editorial cut I ever experienced; the only cut that ever really bothered me. But I mention that as a reminder of where public attitudes still were back in 1996; that even a liberal publication like Entertainment Weekly might worry that praising a natural depiction of same-sex affection might offend some readers, so that sort of praise, my editor felt, had to be tempered or cut.

But Larson was ahead of his time. And he strongly believed that love is love, whether it’s straight or gay; and he helped get that message out into popular culture. That idea was radical in 1996; it’s part of the mainstream today, and Larson helped put it there. All of that I found admirable. I loved the tremendous heart and spirit that came through in everything Larson created. Rapp brings much of that spirit to New World Stages. And I was glad to experience it again. It was important for me to be there.

Watching Rapp in Without You stirred up many memories for me. Sitting in the New World Stages theater watching Without You, I found myself remembering dashing off my thoughts on Rent for Entertainment Weekly, early in 1996, and passionately discussing those thoughts with my editor. And then, as I was sitting in the New World Stages theater, watching Without You, I was surprised to notice—among the many evocative projections on the stage—the Entertainment Weekly Metro cover page for that very write-up of mine from early 1996. (I saved every note I took and every published clipping of mine, relating to Jonathan Larson and Rent. Larson and the show had a tremendous impact upon me.) Seeing that projection on the stage—a page from my own coverage of Rent–put me right back into 1996.

Anthony Rapp and Timothy Britten Parker at the “Rent” cast-album recording session, 1996 (Photo credit: Chip Deffaa)

Larson’s work exerted a strong hold on me. It was meaningful for me to be present at the recording session for the original Broadway cast album of Rent. (I took the black-and-white photo that you’re seeing here–of Rapp and castmate Timothy Britten Parker—while they were recording “Seasons of Love.”) And I was thrilled when Victoria Leacock Hoffman—Jonathan’s intimate friend and indefatigable champion—and her co-producer Robyn Goodman brought Larson’s tick, tick… BOOM! to the stage next. I liked seeing Larson’s work brought to the public so well. It meant a lot to me to attend the recording session for that production, and so on. And so on. Larson’s work speaks to me.

And watching Rapp hold an audience in the palm of his hand for 90 minutes, at the performance I caught at New World Stages, it is clear that Larson’s work continues to speak to many others today. The guest I brought with me to the theater—a respected singing actor who did not move to New York to start his own career until after the Rent phenomenon had occurred—was enthralled. And the whole story was new to him. As it will be to many. But it’s powerful theater. And it’s inspiring.

I know full well how hard it is for an actor to be able to hold an audience by himself (or herself) for 90 minutes. Very few solo shows work well. (And I’m speaking from experience, as one who’s written and directed several well-received solo shows, all of which have been published.) A solo show is a very tough art form. If you have a chance to see Rapp in Without You, you’ll be seeing a memorable production. Thirteen years ago, I watched Rapp offer the first tryout of this show in a bare-bones festival performance. Even then, I wrote it was the most affecting one-man show I’d seen in years. I’m glad that Rapp, creative producer Chris Henry of Royal Family Productions, and her fellow producers (Lisa Dozier, Joe Trentacosta, Lorna Ventura, Charlotte Cohn, Abigail E. Disney, Steve Maler, et. al.) have stayed the course and are finally giving Without You a proper Off-Broadway production. I hope eventually they can get the script published. (It’d be a tremendous showcase vehicle—and learning experience—for any aspiring college theater student with the guts to try it.) And I hope a version can be released in a film or digital format. Rapp himself can always perform this show “live,” wherever opportunities arise.

I only wish Rent were running in New York right now, because Without You would be a perfect companion piece for it. But this solo show works, even if you’re not a Rent aficionado. Rapp is succeeding as both a writer and a performer here. And Without You hits home hard.

Anthony Rapp in “Without You” at New World Stages (Photo credit: Russ Rowland)

Are there minor imperfections? Yes, as in any show. And these are subjective matters. But I’ll mention a couple of things that to me were imperfections. I don’t think the dramatic transition to the song “That is Not You” is quite there yet. The change of mood—which should have a wholly organic, inevitable feel—seemed a little forced to me. I think that if Rapp and the director and music director experimented a bit, a way might be found to get into the energy of that particular song more naturally.

And, for my own tastes, I would have ended the show with the song “Without You.” Just finish that intense song, have a blackout, and leave the audience wanting more! As it is, the song “Without You” is followed by a reprise of the warmer, gentler, calmer “Seasons of Love,” which I personally found a bit anti-climactic. I understand the desire to end with “Seasons of Love”—it is such a familiar and well-loved song, and sends the audience out smiling. But for me that final reprise weakened the impact of the show. It felt like that reprise of “Seasons of Love” had been tacked on arbitrarily to create more of a sweet, happy, feel-good kind of ending. I didn’t feel that dramatically there was a need or justification for that last reprise. I’d have preferred ending more abruptly on the more astringent tone found in the song “Without You.” But that’s a matter of taste, as much as anything else.

I wish Rapp could have found a way to work into the score his own song, “Just Some Guy.” Simply because I’ve long loved that song of Rapp’s. And I’ve included performances of it on a couple of albums I’ve produced. But that’s just a song I really respond too.

Without You—“as is”–is a terrific reminder of both Larson’s strengths as a composer and Rapp’s strengths as a performer. It’s highly recommended.

One final thought. I’d encourage the producers to require that audience members wear face masks in that intimate theater, to reduce the risk of transmission of Covid-19. Such a requirement would reduce chances of audience members getting infected at the theater, and also reduce chances of the star, Anthony Rapp, getting infected at the theater. And since he is the sole performer and does not have an understudy, it would seem wise to provide him with the safest possible working environment. If he’s unable to perform, the show cannot be presented. He is the show. (Producers, protect your investment!)

Right now, I might add, I’m isolating at home, recovering from my first-ever case of Covid. The anti-viral medicine I was given, Paxlovid, has helped a lot, and I can feel my health improving. So I’m not really worried about myself right now. I’ll be OK.

But my doctor says that sitting in a theater (or even a restaurant) with many unmasked patrons is too risky—especially for people who are older or have health issues. He considers theaters to be “super-spreaders,” and does not understand why face masks, which reduce risks of transmission, are not required. He says we still do not fully understand why some people will have few or no symptoms when infected with Covid, while others may develop long-haul Covid, and still others will die from Covid. His only recommendation—especially for his older patients–is to avoid situations in which you’re indoors with a number of unmasked people near you. I could have caught my case of Covid at a theater, at a restaurant, at a bus, or at the recording studio.

My doctor recommends I spend as little time as possible indoors with groups of unmasked people. I love the theater. It’s always been my favorite form of entertainment. I’ve been a constant theatergoer since I was a kid and got to see My Fair Lady in its original Broadway run. And nothing was going to keep me away from seeing Without You. I’m glad I went.

But I want to preserve my health. Right now I’m still dealing with Covid. It’s a drag.

Some theaters (like the Irish Repertory Theatre) continue to require that all audience-members wear masks. I like that. I feel safer there. Theaters that require masks are looking much more attractive to me right now, I must say, than theaters that don’t require masks.

Leave a comment