Irving Berlin and Me (And a Brush with Death Along the Way)

If anyone had told me, when I was a kid, that someday I’d have one of the major collections of Irving Berlin sheet music and would produce more recordings of his music than anyone else on earth, I’d have thought he was crazy…

IRVING BERLIN]

[avatar user=”Chip DeFFaa” size=”96″ align=”left”] Chip DeFFaa, Editor-at-Large[/avatar]

It almost astonishes me. But somehow—putting to good use my sizable collection of rare Irving Berlin sheet music–I’ve produced more recordings of Berlin songs than anyone else living. I sure hope–if the fates allow–to produce still more, because I really love this work and the people I get to work with. I’m grateful for each day that I get to do this. As for the future, though, I guess we’ll see.

In the past 20 years, I’ve produced a total of 34 different albums; 16 of them have dealt with Irving Berlin (1888-1989). The newest album in this ongoing Berlin series, Chip Deffaa’s Irving Berlin: Love Songs and Such–featuring such gifted artists as Betty Buckley, Karen Mason, Steve Ross, Anita Gillette, Jon Peterson, Natalie Douglas, Jeff Harnar, Sarah Rice, Bobby Belfry, Keith Anderson, Molly Ryan, and Seth Sikes–was the hardest of all the albums to produce. And, for reasons I’ll address in a bit, it took by far the longest time to produce; life is not always easy. But for me, this is the most satisfying album of the bunch. (And as I type these words, I’m happy to note it’s just been nominated for a MAC Award, which is extra gratifying!) I know I’ve made a worthwhile contribution to Berlin’s recorded legacy.

I often get asked: “Why are you doing this—recording so many albums of Irving Berlin’s music?,” “What’s it been like?,” and “What’s the hardest part?”

I’ll try to provide some answers today. I know that this will bring up plenty of good memories for me–as well as some not-so-good ones. Because, while making this album, I’ve faced the greatest health challenges of my life. And that’s part of the story, too—coming so close to dying. I’m still dealing with that reality and its implications. And in this detailed autobiographical piece, I’d like to talk about that, too.

But first, let me note: If anyone had told me, when I was a kid, that someday I’d have one of the major collections of Irving Berlin sheet music and would produce more recordings of his music than anyone else on earth, I’d have thought he was crazy. It pretty much seemed to just happen, in its own natural way. It not only felt easy—for such a long time, anyway–it felt like something that I was simply meant to do. Let me tell you about it….

* * *

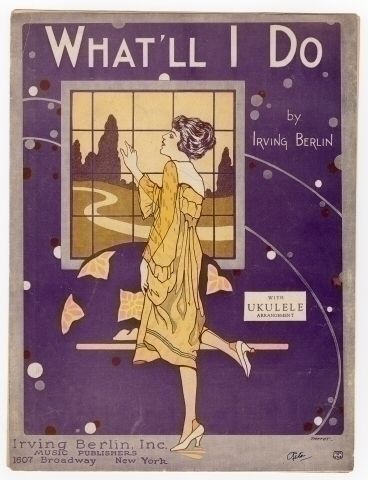

Berlin’s songs—like George M. Cohan’s–have always spoken to me. For my ears, no one’s written a more perfect love song than Berlin’s “Always.” (I’ll play the first seven notes of that song on the piano, sing the words that go with them—“I’ll be loving you… always”–and just marvel at the beauty and economy.) And no one’s written a more haunting love song than “What’ll I Do?” Those are two of my all-time favorite songs right there.

Berlin’s high-spirited numbers, from “When the Midnight Choo-Choo Leave for Alabam,” to “Steppin’ Out with My Baby,” are—for me—no less irresistible. The words, the music, the infectious rhythms all get to me. Berlin—and this is rare–was equally strong as a composer and a lyricist. He wrote succinctly and from the heart. He said he sought to create songs that expressed what the average person was feeling, in phrases that the average person could easily sing. He said his goal was simplicity–adding that achieving that goal required far more hard work than most people could imagine.

Berlin wrote more hits—and made more money—than any of his colleagues in the Golden Age of American Popular Song. When you look at the creators of the Great American Songbook, Berlin—along with the Gershwins, Cole Porter, Jerome Kern, and a few others—is in the very top tier. Gershwin, incidentally, called Berlin the greatest of all American songwriters. And when Jerome Kern was asked what Berlin’s place in American music was, Kern famously proclaimed: “Irving Berlin has no place in America music; he is American music.” Berlin, in turn, was never shy about expressing his admiration for Cole Porter, the Gershwins, Jerome Kern, Harold Arlen, and his earliest major source of inspiration, George M. Cohan. (He kept a portrait of Cohan in his office all of his life.)

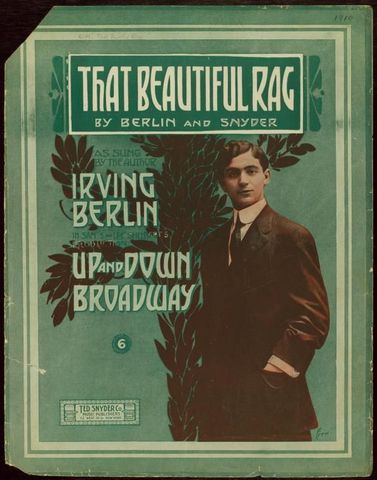

SOME IRVING BERLIN SHEET MUSIC

Berlin wrote more than 1200 songs. He created the scores for 18 Broadway shows and 19 Hollywood musicals. And, remarkably, he did all of this with almost no formal education. As a young artist he was turning out the best-selling songs in the world even though he could neither read nor write music. He had musical secretaries set down on paper numbers that he played by ear, and sang, and hummed, and whistled. And he also negotiated his business deals by himself, trusting his New York City street-smarts to get from Hollywood the most lucrative contracts any songwriter had ever gotten; he did not have an agent. The more I learned about Berlin, the more intrigued I became by the man, as well as his music.

* * *

In my youth, I heard Berlin’s songs the same way that many people have—I watched on television such classic Berlin musicals as White Christmas, Blue Skies, Top Hat, Holiday Inn, and Easter Parade. They’re part of America. I loved those musicals so much, I’d set our family’s Wollensak tape recorder in front of the TV, so that I could make audio recordings of the songs, which I listened to over and over again in my youth.

Growing up, I also had an unusual added advantage in that I was befriended, mentored, and directed by an aged ex-vaudevillian named Todd Fisher. He’d show me old photos from his career, and tell me about playing the Palace Theater—the Mecca of vaudeville—way back in 1913. And what it was like working with Gypsy Rose Lee, her sister, June, and Momma Rose, when they were all young. In the years that I knew him, he was up in his 70’s and 80’s , but he was still vital and still occasionally mounting musical shows locally. And he taught me early Berlin songs to perform onstage, from vintage original sheet music that he’d owned since the songs were brand new. He even gave me some of his sheet music to keep. (I loved the beauty of the oldtime covers.) He was teaching me numbers like Berlin’s suggestive “You’d be Surprised” before I was old enough to even fully understand them. I was the youngest performer he worked with, the only boy. He usually worked with older people–some as old as he was.

He’d promote his shows as having “all-star casts.” I told him I was sort of embarrassed by that “all-star” billing; I was just a kid having some fun. Oh, I’d done a little bit of professional acting work but I was hardly any “star.” He’d say in response, “To me, Chipper, you are a star; I can see it in you. But phrases like ‘all-star’ aren’t meant to be taken literally. Every place I worked in the old days—whether it was a top theater in New York or some rinky dink hall in Altoona—said they were presenting ‘All-Star Vaudeville.’ That’s part of the tradition. You wouldn’t want me to turn my back on a hundred years of tradition now, would you?”

VINTAGE POSTER ADVERTISING “ALL-STAR VAUDEVILLE”

And when I protested that I wasn’t any great singer; I didn’t have a trained voice or a big range, or anything like that, he’d say: “You’ve got something much better; you’ve got the show business in you, Chipper. They would have loved you in vaudeville. So you’ll talk/sing your songs—just like I did, and George M. Cohan did, and Ted Lewis did.

“Didn’t you ever see Irving Berlin sing his own songs in vaudeville, Chipper? Irving had such a tiny voice, but he could still put a song across. And don’t you remember the way Sophie Tucker introduced Berlin’s ‘The International Rag’? She announced it, she talked it and she shouted it, as much as she sang it. And Sophie was a sensation. Everyone loved Sophie, every acre of her. Don’t you remember?”

I’d ask him: “When was that, that Sophie Tucker introduced Irving Berlin’s ‘The International Rag’?” He’d say, “Oh, I guess that must have been around 1915, 1916.” I’d have to remind him that I wasn’t even born then, that my parents weren’t even born then. And then he’d demonstrate for me the way Sophie Tucker used to sing the number, giving me his best impression of her. “She knew just how to hold back a bit at the start so she’d have room to build, and make the song even bigger at the end. No one could sell a song better than Sophie.

SOPHIE TUCKER

“Do you think Irving Berlin wanted opera singers singing his numbers? No, he wanted people with personality who could sell ‘em. I’ll teach you how to do it! Today we’ll work on a cute number, ‘Some Sunny Day,’ that’ll be perfect for you. This song really is a gift that I’m giving you. A gift for life. You’ll thank me.”

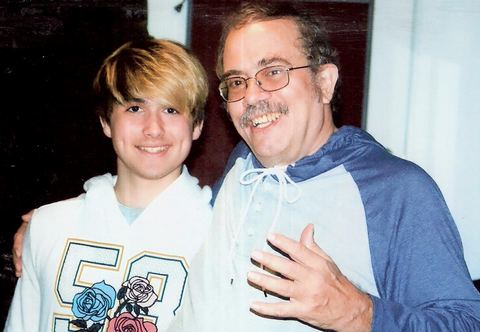

I still enjoy talk/singing Berlin songs that Todd Fisher taught me way back when I was a kid. And I also enjoy passing on to young performers today some of the valuable lessons that he and others taught me. On the latest Berlin album, I get to sing “Some Sunny Day” with one of the very best young singers around, Jack Corbin, who’s 18, and you can hear what a good time we’re having—so much sunshine in both of our voices! (I sure love singing with Jack.) And as we recorded that song, I was remembering Todd Fisher teaching it to me, and singing it with me, when I was young; and now I’ve passed it on to Jack, who’s really quite wonderful. I like being part of that whole big cycle of life.

Being a collector by nature, in my youth I also gradually began collecting some Berlin sheet music, just as I’d already begun collecting sheet music of my original favorite composer, George M. Cohan. Back then, vintage sheet music was plentiful, inexpensive and easy to find. I had no idea, as I occasionally picked up some eye-catching old sheet music (and old 78 RPM records) from second-hand shops, that I was on my way to amassing a major collection. I was just following my interests, the way another boy might collect baseball cards.

Todd Fisher and I would read the showbiz newspaper, Variety, together, and I felt like I was part of this great, important world of show business. “Let’s see what’s in the Variety this week,” he’d say. (He always called it “the Variety.”) I was so fascinated, I actually went into the office of Variety (which back then was in the heart of New York’s theater district) and tried to talk them into hiring me—even though I was just a kid. They told me to come back in 10 or 20 years….

JACK CORBIN AND CHIP DEFFAA

* * *

OK, let’s move ahead to when I’m a little older…. For 18 years, I wrote for The New York Post. It was great fun, most of the time, writing about jazz, cabaret, and theater. And I was out constantly, seeing the talent in clubs, concert halls, theaters. I had free access to all of the live entertainment New York had to offer. I relished seeing it all, and writing reviews, interviews, listings, and features. Through my work, I got to meet seemingly everybody.

There was one person I wanted to meet but no one seemed able to see him anymore: the legendary Irving Berlin, who was then nearly 100 years old. For about the last 20 years of his life, Berlin was famously reclusive, rarely leaving his home at 17 Beekman Place, NYC. I happened to know some people–like writer James T. Maher–who’d once been able to visit Berlin, but could now only have contact with him through occasional late-night phone calls, if/when Berlin decided to call. Maher assured me that Berlin was still “all there” and was still as feisty (or cantankerous) as ever; he mostly just wanted to be left alone.

When I wrote an article in The New York Post, announcing that Michael’s Pub—one of the city’s top supper clubs—was going to present a salute to Berlin, telling his story through his songs, Berlin read my piece. He angrily telephoned Gil Wiest, the owner of Michael’s Pub, threatening legal action unless the show was cancelled. Berlin said he did not want any unauthorized salutes, tributes, or attempts to tell his life story in any way—not while he was alive. After he was gone, he told Wiest, people could do whatever the hell they wanted. But not now! Wiest was one tough cookie, but he wasn’t about to get into a legal battle with a man as famously rich, stubborn, and tenacious as Berlin.

Wiest then phoned me, saying he was being forced by Berlin to cancel the show, costing him a lot of money—and he blamed all of that on me. Wiest told me: “Berlin was furious when he read your story in the Post.” But what caught my attention was Berlin’s offhand comment, as relayed to me by Wiest, that people could do shows about him after he was gone. That gave me a little something to think about.

That winter, my friend singer/songwriter John Wallowitch, who shared my passion for Berlin’s music, invited me to join him and some other friends, to go caroling outside Berlin’s house. John’s idea was that, at 6 pm on Christmas Eve, we’d stand outside of Berlin’s home and then—instead of singing traditional Christmas carols—we’d sing Berlin’s “White Christmas,” “Always,” and “God Bless America.”

JOHN WALLWITCH

I thought John had a sweet idea, but it was freezing cold that December 24th—just nine degrees outside. I told John I was going to pass on his invitation and spend Christmas Eve with my folks instead, casually adding, “Let me know how it goes, John, OK?” I didn’t expect much.

But the next day, John called, excitedly, and told me what I’d missed. And boy, was I sorry that I hadn’t gone! John had gathered 18 friends. After singing their three songs outside of Berlin’s home, John knocked on the door. To everyone’s surprise, John told me—making the most of every detail he shared–the aged Berlin answered the door himself. He was wearing a brown, monogrammed bathrobe. He invited everyone in; he served them hot chocolate, gave them hugs, kissed the women on their cheeks, and told them all they’d given him the best Christmas of his life. Extraordinary!

(Incidentally, the tradition that the late John Wallowitch started that night continues to this day. Each year, a group of us–now led by the tireless Jacqueline Parker, who was part of the original group back in the 1980’s–gathers at 6 pm on Christmas Eve outside of Berlin’s former home, to sing the same three Berlin songs. I’m glad to help keep that tradition going nowadays, when I can.)

I told John Wallowitch that this was one of the few real regrets of my life—that I’d missed out on that chance to meet, however briefly, my favorite living songwriter. John suggested I write something about Berlin someday, maybe a book or a play, and put to good use all of my knowledge about Berlin (and collection of rare sheet music). I promised John that if I ever did write a play about Berlin—I kinda liked that notion–John would be a character in it!

* * *

Eventually, I created the first published show about the life of Irving Berlin. Then another one. And then another one. When I get into something, I really do tend to get into it! And when I’m writing a book or script, I can get happily lost in the process; I mean I lose all sense of time and place, and can spend a whole day writing, forgetting about eating or sleeping, or even stretching my legs. (That’s the way it was for most of my life, anyway.)

I’ve now written a total of six different shows about Berlin, each featuring some different songs and stories, each for a different-sized cast. And my late friend John Wallowitch, I’m happy to note, is a character in several of the scripts.

I like writing different scripts on the same subject. I like to look at a subject from different angles. I might note, for example, that I’ve also written six different published scripts about George M. Cohan, three different published scripts about Fanny Brice, and three different published scripts about Eddie Foy and the Seven Little Foys. (My agent, Peter Sawyer, says he’s never met anyone else who likes writing multiple scripts about the same subject, but that’s just the way I am.)

All of my Irving Berlin shows are now published and available for licensing: Irving Berlin’s America, Irving Berlin: In Person, Irving Berlin & Co., The Irving Berlin Ragtime Revue, The Irving Berlin Story, and Say it With Music. If a school or college, or a community theater or regional theater, or any producer anywhere wants to mount a show about Berlin, from a one-man show to a full-scale production, I’ve got a good script and score for them. (One theater company recently combined two of the shows for its production!) The scripts could also easily be adapted into a film or TV special, or a limited TV series.

THE SCRIPT FOR “IRVING BERLIN’S AMERICA”

Having written so much about Berlin, I was getting ready to move on. But publishers of my scripts suggested I produce cast albums for the shows. I liked the idea of preserving the work of the talented actors who’d helped develop and perform my various shows in productions at New York’s 13th Street Theater and elsewhere. And thus far we’ve made cast albums for five of the six different Berlin shows that I’ve written.

When we were finishing up the cast album for The Irving Berlin Ragtime Revue, one of the dozen singers in the cast said, “It’s a pity we couldn’t include some of the numbers that you had to cut from the show to get it to the right length.” And for me, at that moment, a light seemed to go on!

When I was writing the various Berlin shows, I’d carefully reviewed every song that Berlin had ever written or co-written—more than 1200 different songs in all. I doubt there’s anyone living who’s more familiar than I am with Berlin’s total body of work. My early drafts of each of the shows always included some intriguing, rare songs that eventually wound up being cut. (My scripts almost always start out extra long and then I begin pruning.) And now I thought: We could make a whole album of rare Irving Berlin songs!

Over the years, I’d gradually built up a terrific repertory company of performers who were good at interpreting vintage songs—loyal, talented singing actors who’d done shows of mine celebrating not just Irving Berlin, but also George M. Cohan, Fanny Brice, Johnny Mercer, Eddie Foy, and more. I had a core group of gifted, reliable artists who could carry off with zest Berlin’s music.

I also knew the larger pool of talent out there—seasoned singers in the Broadway and cabaret communities who could handle this music well. I had a lot of friends in the business. And so I really felt uniquely qualified to do a Berlin album; I knew well the songs that he’d written and I knew well suitable performers to interpret the songs. I began making a few phone calls, to ask artists if they might like to learn and record some rare–and, in some cases, never-before-recorded–Irving Berlin songs. To my surprise, everyone I reached out to said yes, they wanted to be part of my Berlin project.

* * *

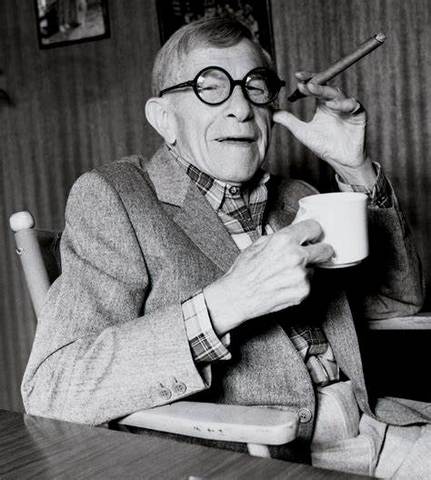

Years ago, one of my favorite people in the business, George Burns, taught me (among many other valuable lessons) that in putting together an act or a concert or an album, the first thing you needed to work out was how you wanted it to open and how you wanted it to close; it was essential to have the strongest possible start and finish. In planning the first Berlin compilation album, I knew I wanted Natalie Douglas to open it and Beth Bartley, another great favorite of mine, to close it.

GEORGE BURNS

And when Natalie Douglas, a highly respected, MAC Award-winning cabaret star I’d long appreciated, came into the studio and sang a never-before-recorded Berlin rarity that I’d found, the wonderful “Bring Back My Loving Man,” I knew we were on to something. She put a lot of work into learning and mastering that long-lost song. And sure did it justice. (She asked me: “Do you want me to sing this slowly or with more of a music-hall feel? It’ll work either way.” I left that choice up to her.) At day’s end, I left the studio beaming. I didn’t care if anyone else liked the album we were making or if it sold only two copies, I already knew that I would love it.

The album wound up getting good reviews and it sold surprisingly well for an independent album of songs written so long ago. When one fan, Jhon Marshall, wrote me, asking when the next album in my “Berlin series” would be coming out, I decided to do a follow-up album. I actually hadn’t been thinking in terms of any “Berlin series” until Jhon Marshall suggested it. But I liked his idea and thought: Wouldn’t it be cool if we could eventually record all of the unrecorded Berlin songs? I like having goals, even if they’re not always practical.

And then Berlin experts, like the extraordinarily generous Michael Deatz, offered to provide me with any Berlin songs I might not have. He sent me scans, on computer discs, of tons of sheet music—every song in his collection. I had many of these songs already, but that extraordinary generosity of his felt to me almost like an omen that I should move forward.

And a couple of other Berlin experts whom I thought the world of, Benjamin Sears and Bradford Conner, and sheet-music collector/pianist Michael Lavine were equally kind and supportive, and got me some really rare stuff no one else had. And Stephanie Rinaldo’s wonderful Hollywood Sheet Music was, time and again, an invaluable resource. (I can’t tell you how many times she came through on short-notice with replacement copies of Berlin sheet music I’d misplaced; I’m really good at misplacing things!)

So we made another Berlin album, and then another, and still another, recording hundreds of songs in the process: Irving Berlin Revisited, Irving Berlin Rediscovered, An Irving Berlin Travelogue, Irving Berlin Ragtime Rarities, The Irving Berlin Duets Album, Irving Berlin: Sweet and Hot, and more. Slau Halatyn’s BeSharp Studios, in Astoria, became like a second home for me. My big old Lincoln Town Car could practically drive there and back by itself; I spent so much time there.

In making these albums, the rewards for me were–and are–plentiful. I’m glad to record some of my favorite seasoned pros singing these songs that I love. I’m glad to shine a spotlight on some of the promising rising younger artists I’ve found, as well. And of course I have fun making occasional cameo appearances myself on the albums, cheerfully talk/singing numbers that I’ve cherished since boyhood. (That’s pure joy.) Todd Fisher taught me well!

* * *

The newest album, Chip Deffaa’s Irving Berlin: Love Songs and Such, has the strongest mix of songs and the strongest lineup of talent of any of the albums I’ve produced. It’s also taken–for reasons I’ll discuss in a bit—far longer than any of the other albums to complete. (Life sure has ways of surprising you.) But completing this album, despite some formidable challenges, has meant so much to me.

“IRVING BERLIN: LOVE SONGS AND SUCH” CD

I began working on the list of the songs and singers that I wanted to include about five years ago. (That’s a long time ago; albums usually move along much quicker.) On my previous Berlin albums, I’d focused primarily on rare and previously unrecorded songs. I’d deliberately avoided many of Berlin’s most popular songs because they’d been recorded many times before.

But I kept getting requests from listeners to include on future albums such Berlin evergreens as “Always,” “Let’s Face the Music and Dance,” “Stepping Out with My Baby,” “How Deep is the Ocean, “What’ll I Do?” “Say It Isn’t So,” “Love, You Didn’t Do Right By Me,” and “Blue Skies.” And so I decided that all of those famed standards, and more, would be included on Irving Berlin: Love Songs and Such.

I also discovered, in my talks with younger singers and actors I knew, that plenty of younger people had never heard the classic versions of Berlin standards by Bing Crosby, Al Jolson, Rudy Vallee, Fred Astaire, Ella Fitzgerald, Nat King Cole, and Rosemary Clooney that once were widely known. Many of Berlin’s best songs—and the great singers who’d sung them–were unknown to a lot of younger people today. All the more reason, I felt, to make some fresh recordings now.

* * *

I knew I wanted the album to open with Karen Mason singing “Always” and close with Betty Buckley singing “Blue Skies.” Those are two of my favorite living singers and two of my favorite Berlin songs. And I knew that those singers already had those songs in their repertoires and sang them superbly; they connected with those songs, found their own rewards in them, sang them their own way.

KAREN MASON

And when Karen Mason—whose work I’d admired for some 30-odd years—came into our studio and began running through her own version of “Always,” with my longtime music director, pianist Richard Danley (who has such a great feel for this music), I knew we were off to a strong start. And I had Grammy-winner Andy Stein—my absolute favorite living violinist; no player is more lyrical—adding exquisite, lacey violin lines.

There were other artists I just had to include because I knew they interpreted Berlin so well.

No one has more Berlin songs in his repertoire—or interprets the lyrics more thoughtfully–than singer/pianist/vocalist Steve Ross—“the Crown Prince of cabaret,” as the New York Times has called him–whom I’ve been enjoying in “live” performances since the 1970’s. I told Steve: “Come to our studio any day it’s convenient for you, and record any song of your choice. I’ll make sure the grand piano is freshly tuned for you.” He recorded one of the reflective Berlin medleys–aching with loss and longing—that only he could come up with: the forgotten-but-moving “Maybe it’s Because I Love You Too Much” segueing into the plaintive, famed ”What’ll I Do?”

And I can’t tell you how much it meant to me to have Anita Gillette come to our studio to record. She was a star of Berlin’s last Broadway musical, Mr. President, in 1962—a direct link to the master!–and has presented cabaret shows devoted to his music. I’ve long enjoyed her work on stage, screen, and television. And she was a great delight, romping joyously in counterpoint with pianist/vocalist Paul Greenwood through “Pack Up Your Sins and Go to the Devil in Hades” –which Berlin said was the hardest of his songs to sing. She just lit up BeSharp Studios with her energy! Our recording engineer, Slau Halatyn, who’d caught her by chance on TV just the night before (on a rerun of 30 Rock), was beaming as much as I was.

Over the years, I’ve heard singer/pianist Eric Comstock—whom I’ve known since he was 16 (he’s now in his 50’s)–interpret with zest assorted Berlin songs–particularly songs that Berlin wrote for Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers. Comstock just connects really well with the dapper, jazz-tinged songs Berlin created for Astaire in the 1930’s. So I was very happy when he agreed to record “I’m Putting All My Eggs in One Basket.”

I invited Jon Peterson to both sing and tap-dance (as only he can) on “Steppin’ Out with My Baby.” For my money, there’s no greater song-and-dance man working in the theater today. I relished hearing what he could do with that song. Fred Astaire, for whom Berlin originally wrote that song in 1947, is one of Jon’s heroes. But I knew that Jon has a sure enough sense of his own strengths to do the song his own way, not try to copy Astaire. He delivered a first-rate performance.

I asked Stephen Bogardus, a veteran of more than a dozen Broadway shows, to record “Let’s Face the Music and Dance”—and I’ve never heard that superb song sung better. One of my younger singers, who’d seen Bogardus star on Broadway in Irving Berlin’s White Christmas and loved Bogardus’ work on the Broadway cast album of Falsettos, told me he didn’t feel worthy of being on the same album as Bogardus. “I’m not in his league,” the younger singer told me.

STEPHEN BOGARDUS AND CHIP DEFFAA

I told that younger singer, “I’ve known Stephen Bogardus for almost 50 years. Of course you’re not yet at the level he is now; he’s bringing a lifetime of experience to his work. But I see the potential in you; your singing reminds me of his when he was your age.” Incidentally, I brought sheet music to every session for the convenience of the recording artists. But when I offered the sheet music to Bogardus, he said that he’d rather not be looking at sheet music when he sang; he wanted to sing the song, not read notes. (He knew the listener would hear the difference.) That’s one very wise artist! And that’s part of why he’s such a favorite of mine, on album after album. His interpretations of the songs that I give him resonate deeply with me.

I loved being in the recording studio. Sometimes I’d spend the whole day there, getting home 12 hours after I’d left in the morning, and then repeat the process the next day. (I’ve always thrived on working hard.) And for each song, we took as long as was needed; some went quickly, some took hours to record. Sometimes, we’d need to try again with the same singer on different days. Or try again with different singers, if I wasn’t quite satisfied with a particular recording. There was no rush; I wanted to get things just right.

I enjoyed every part of this process.

So why did this album take far longer than the others to complete?

Well, I don’t much like writing about this–or even remembering it. But I do need to remember it. And I believe that writing it all out now, even if it’s difficult for me, will be helpful to me. For life’s not always as easy as one might wish it was, or imagine it should be.

When I was about halfway through making this album, I nearly died. I don’t like recalling that period at all. And I’m still trying to make sense of it all. I get asked a lot about it by acquaintances.

Here’s what happened, and here’s where things stand now.

* * *

All my life, I’d enjoyed such ridiculously good health, I took good health for granted. I’d never in my adult life had to spend a night in a hospital. I didn’t need to take prescription medicines. I didn’t need to see specialists—just a family physician whom I might call once every few years to ask for some cough medicine if I caught a pesky cold.

Oh, I occasionally mentioned to my doctor some seemingly minor complaint or another—a persistent dry cough I’d had in recent years, for example, or some sharp muscle cramps in my legs, or a tightness in my chest, or me getting winded, feeling short-of-breath on hikes that used to be easy. And I’d just felt tired a lot for the past year or so. But he assured me that these various issues were insignificant, the sorts of random things that were just part of being alive (and growing a bit older). The persistent light cough might simply be my reaction to air pollution, he suggested. Or maybe the air in my home was too dry; to my doctor, that non-productive little cough of mine really didn’t seem to be a big deal. Nor did occasional sharp muscle cramps that I mentioned seem worrisome to him. And if I was getting winded on hikes these days, well, he said, I wasn’t quite as young as I once was. And maybe I was just pushing myself too hard. If I felt tired sometimes, he suggested I get a bit more rest. It all seemed like good, common-sense advice.

He stressed that my EKG looked fine, as did my bloodwork; he saw nothing to worry about. (Later, looking back, my doctor would say that these various occasional symptoms that I’d mentioned to him, considered collectively, were all reflections of developing heart and lung problems but they seemed too subtle to demand attention at the time.)

As my doctor often told me, my vital signs were always excellent when he saw me. I always appeared to be in good shape. I generally looked so happy and healthy, I had such few complaints, and I came from such hardy stock, he felt good about my overall health. My mom, I might add, made it to the age of 89, my Dad to 95—and my Dad was still swimming laps in the lake with good cheer in his 90’s. I hoped to follow in their footsteps.

I loved my life, and worked hard with zest. I never took vacations, except for an occasional day or two to go hiking; I never wanted to take a real vacation (and repeatedly turned down offers to do so); my work was rewarding. And from time to time I did get to do some traveling overseas, which was always work-related (like directing a play of mine in Korea, or being invited by the government of Denmark to participate in a Duke Ellington symposium, or being invited by the U.S. State Department to give lectures on theater). I was fine with all that. I enjoyed my life—the work and the people close to me. No complaints!

For relaxation, I’d take a little walk in the woods, by myself or with friends, up here on Garret Mountain where I live.

Most days I’d feed the deer on the grass outside and sing to them; they knew me, and would come up to me as soon as they saw or heard me. I’d call each deer by name. (Some have known me since they were born and they know me well.) I loved those little breaks.

CHIP FEEDING THE DEER FROM HIS HAND (Photo credit: Jonathan M. Smith)

By choice, I wrote virtually every day (including holidays), seven days a week, putting the same hours in every day whether I was working on a book or a play or a song or an article. Since I was 19, I’ve logged every hour that I’ve spent writing. (I do like to keep lists and records.) My work habits have remained consistent for nearly five decades. Writing gives me joy. (I have some writer friends who tell me they don’t enjoy writing at all; I just don’t “get” that. I don’t understand why they even write if they feel that way—for I really love losing myself in the process of writing and it’s fun for me–but I guess we’re all different.)

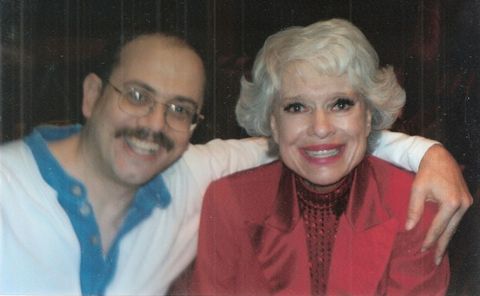

As a writer, I never missed deadlines. If I caught some little winter bug or occasionally—more often in the past year or so—felt tired to the bone, I just powered myself through it. “Mind over matter!,” as the indefatigable Carol Channing taught me years ago. (She taught me well.) And the show would go on.

Somehow I always got the work done. I didn’t drink or do drugs; my work gave me all of the natural “highs” I could ever ask for. I lived a go-go-go kind of pace, and loved my life. I imagined my life would always be like that.

* * *

And then on the morning of August 2nd, 2019, while walking across the room in my home here in New Jersey, I suddenly, unexpectedly collapsed and passed out. I knocked over–and broke–a large, standing floor fan as I toppled down over it, bruising my ribs. When I came to and tried to get up, I once again collapsed and passed out. And then that happened still again. Three times. I simply could not stand up and maintain consciousness. I could not make it to the phone.

I lay on the floor in my living room, dazed. I could not understand what was happening to me. And then by sheer chance, two friends stopped by for a random, surprise pop-in visit. (Normally I hated such visits and always tried to discourage them.) By that point, though, I was clearly having difficulty breathing; my friends, alarmed, called 911 (and also called my brother and sister) and got me to St. Joseph’s Hospital. I was given oxygen to help me breathe. At the hospital, after performing various tests and scans on me, a doctor told me that if my friends hadn’t stopped by for that random visit, I’d have quietly died right there in my home. I heard those words but found that hard to believe.

The doctor said he wanted my consent so that he could begin a critical medical procedure right away. But I quickly cut him off! I said that for the last few days I’d felt exceptionally weary; there was no denying that–but my health, overall, had always been excellent. I told him that I’d been feeling over-tired of late—we all get over-tired sometimes, don’t we?–but I was sure I was fundamentally all right. I really didn’t need to be in any hospital, I argued; I said that my friends, although well-meaning, had over-reacted. I’d sent them on their way, insisting there was nothing to worry about.

The doctor then said to me quietly and evenly that the health challenges I was now facing were “grave.” (That unforgettable word “grave” caught me up short; “grave” is simply not a word you’re used to hearing.) He said that I was suffering from pulmonary embolisms and congestive heart failure, and he needed to act now. But I still didn’t want to hear him.

I asked the doctor: “If I consent to this procedure that you’re recommending we try, will I be as-good-as-new afterwards?” He answered, matter-of-factly—he wanted me to give informed consent–that he could not make any guarantees as to the procedure’s long-term effectiveness; there were no guarantees at all at this point. But if he did not try to do something right away, he told me, I would die. He said: “You have two killer clots. And a number of smaller ones.”

Those stark words “killer clots” hit hard. I’d known people younger than me who’d died from pulmonary embolisms (which are blood clots lodged in the arteries in the lung). And others who had died from congestive heart failure. I didn’t like those words.

I told the doctor, almost grudgingly, to go ahead then, and he soon had a team of eight people working on me. They put a catheter up through my groin into my heart, so they could apply TPA (“tissue plasminogen activator”) to try to dissolve the two worst clots. I was conscious through all of this. I quietly watched everything, though, almost as if it were happening to somebody else. I just had trouble accepting the danger I was in. (Denial can be a very powerful thing.) Doctors, I told myself, often did make mistakes.

The doctor told me that one of the two big clots was fresh, the other was so hard and well-organized it had probably been in place for a year or more, reducing the oxygen that I’d been getting. He asked if, in the past year, I’d had any symptoms such as a dry cough, or getting short of breath, or feeling tightness in my chest. I told him I’d had all of those symptoms, but they hadn’t really seemed important; he said those symptoms were all caused by clots in my chest. And the sharp muscle cramps in my legs that had periodically bothered me in the past year or so were caused by clots in my legs: deep vein thrombosis. He said I was very lucky to have escaped death; most people with clots like these were not so lucky.

As the medical team was finishing up, one young nurse, smiling broadly, paused to take a selfie with me; I supposed I’d become an object for a social-media posting by her (“Here I am at the hospital with some guy whose life I helped save today.”) It all just seemed surreal.

The next day, I was resting in a Critical Care room and on oxygen, with doctors telling me that I had additional issues they needed to address. Today they were hooking me up to some equipment to hit me with heparin and ultrasound (“EKOS treatment,” they called it) to continue trying to help break up clots. I muttered that I’d really hoped that by now we’d be all done with everything and my life would go on just like before. I told them: “I’d really like to go home now, if that’s all right. Could we skip this EKOS stuff? If I get a little rest at home—just take things easy for a day or two–I’m sure I’ll be fine.”

The doctor told me, “You’re not going anywhere. And for the next 24 hours I don’t want you to move at all. You mustn’t even try to sit up! We’re not out of the woods. You have a lot of clots, and fragments of clots, in you–in your legs and in your chest. Some of the clots that formed in your legs moved up into your chest. We’re not sure why you have so many clots; it’s possible there’s even a genetic factor at play here—but they pose real risks.” And there were other complications he mentioned but I just turned my head to look away; this was all hard to accept.

My brother, Art, and my sister, Deb (who’d flown in from California), asked me if there was anything they could do for me. I was lying flat on my back. I complained to them: “The doctors here won’t even let me sit up right now! I just have to lay still on my back like this. But if you two could hold Deb’s laptop over my head and I can reach up and type, overhead, I’d like to write a ‘Happy Birthday’ greeting for one of my singers, Jack Corbin. I wouldn’t want him to think I was forgetting him on his birthday today, August 3rd.” And my brother and sister helped me do just that.

* * *

Over the next week or two, I gradually came to realize that my overall health had changed radically. I now started each day with a handful of prescribed pills. I was told I’d need to be on blood thinners for the rest of my life, and also on diuretics, and on blood-pressure medicine, and so on. The doctors hoped that the blood thinners would stop new clots from forming, and my body would, in coming months, dissolve the many clots that were still in me.

ST. JOSEPH’S HOSPITAL

I did not feel well at all. If I exerted myself even a little bit, I’d experience breathing difficulties and would start moaning uncontrollably. (I’d never in my life moaned before.) My heart would pound very hard and race out of control, in a way that it had never done before, alarming me. None of this made sense to me.

And I’d acquired a whole array of attentive specialists. I was told I’d need to be seeing specialists like this for the rest of my life: a cardiologist, a hematologist, an endocrinologist, a vascular surgeon, a pulmonologist, and so on. Each doctor seemed to have a different view of my likely outcome.

* * *

One doctor told me flatly that I was dying. When I asked the next doctor if I was dying, he replied diplomatically: “We are all dying… But we’re trying to stabilize your condition.” Seeking reassurance, I asked a third doctor if he believed I might make a full recovery. He thought a bit before responding: “God-willing… But none of us knows how much time we have. Some people will recover from a pulmonary embolism in six months, or a year, or two years; some do not recover. Each individual is different. You came very close to dying. Part of your lungs has died; clots were shutting off the blood supply. And the build-up of pressure caused by the clots put a strain on your heart. That causes problems.” I tried to cling to his words that some people recovered in six months; that’s all I wanted to hear.

The vascular surgeon wanted to put an IVC filter (an inferior vena cava filter) in me, to prevent any other clots in my legs from reaching my heart or lungs with what he termed “possibly catastrophic results”; and my cardiologist seconded that recommendation.

But I just did not want any more procedures. What bothered me most, I told the doctors after about a week, was that I felt so thoroughly fatigued—I’d never been so fatigued in my life. But the vascular surgeon said that when I breathed, I was now getting less oxygen than I used to get; that was part of the problem. And my circulation was impaired. And in addition, he said…

But I simply couldn’t absorb all that he was trying to tell me. I tuned him out. I just desperately wanted everything to be back to “normal.”

The vascular surgeon cautioned me that my overall condition was not going to get better and might very well get worse, and said I might need a wheelchair in the future. (By this point I was using a walker, and needed to stop every few steps to try and catch my breath.) He told me: “Surely you must agree—if it should come to this—that being confined to a wheelchair would be better than dying.” I told him I was not at all sure that I agreed.

I appreciated every kind note, card or gift that friends sent, from a care-package of treats sent by Broadway veteran Ray DeMattis to a stuffed plush deer (my favorite animal) sent by improv comic Carl Kissin. The doctors said I shouldn’t have visitors, outside of family; I needed complete rest. But I said that Keith Anderson and Mark Pugliese (who drove 250 miles to see me as soon as he heard I was ill) were like family. I told my friends I was confident I’d be fully recovered within six months or less. And worked hard to show them how quickly I could walk a short distance in my walker—trying to convince them (and convince me) that I was actually recovering quite well, thank you. But by a brief visit’s end, I’d be just beat. When my energy was gone, it was gone. And I’d reach that point suddenly, without warning. When a visit or a call from a friend ended, I’d often simply just crash, fall deeply asleep.

* * *

From the hospital I went to the Actors Home in Englewood, New Jersey. I was supposedly there for physical rehabilitation. But they had me spending every day lying in bed, resting, except for 40 minutes of physical rehab, which didn’t seem to be doing much good. They didn’t want me leaving the bed at all unless a nurse or aide was by my side to assist. And the nurses and aides always seemed to be so busy.

I felt like I was losing ground each day that I was there. I felt I was atrophying, decompensating from all of the bed-rest. My legs felt weaker. I felt more unsteady on my feet. And was getting light-headed. I had several falls, which alarmed me. They put a wrist-band on me, to alert the staff that I was in “at high risk of falling.” I feared that if I stayed there a few more weeks, resting in bed almost round-the-clock, I might become a total invalid and never get out of that place.

THE ACTORS HOME

I kept thinking of a friend of mine, singer Baby Jane Dexter, who had died in the Actors Home just a few months before. I had the same people caring for me who’d cared for her; they told me they recalled her as “very nice.” It unsettled me that the same people who were caring for me now had cared for my friend until she’d passed away.

The Actors Home, I must stress, has a good reputation among assisted-living facilities. If I ever have to return there someday, it’s better than most such places for the old and infirm. And I realize that a day may come when I’ll need to stay in a place like that.

I thought of George Burns’ character in The Sunshine Boys, winding up spending his final days in the Actors Home in New Jersey. But I can’t say I met anyone nearly as charming as George Burns while I was staying there. I was basically confined to my bed. I felt isolated, warehoused. I was cut off from the activities of the world. And my elderly roommate watched TV loudly all day and well into the night. (I craved ear plugs.) I didn’t want to stay in that facility a minute more than was absolutely necessary at this time.

After eight days, I phoned one of my friends, actor Michael Townsend Wright, and asked if he could come and get me, and take me home. I told him: “Please, Michael! Help bust me out of this place!’” Against doctors’ advice, I checked myself out of the Actors Home early. They insisted it was too soon for me to leave, that I was dealing with ongoing health issues more serious than I seemed to realize, and I needed their round-the-clock care. I told them that once I was back in my own home, I’d surely feel more like my old self. They tried to impress upon me that my condition was serious.

Maybe so; I guess I was starting to understand that. But I also felt that if my time on Earth was limited, I wanted to spend it in my own home.

* * *

Normally, I’m a voracious reader, often reading two books at once. And a couple of friends thoughtfully gave me books as get-well presents. But now, for the first time in my life, I found I was so fatigued that I simply didn’t have the energy to read, or to listen to music, or to watch TV.

I did not turn on the TV once for four months after returning home. I could simply rest for hours on the couch—as if hypnotized–doing absolutely nothing. I’d just be looking at the twinkling lights on the little Christmas tree that I keep in my home year ‘round. I’d never in my life simply “done nothing” like that before—I usually needed to be doing a couple of things at once (maybe watching a TV show while also reading a book or working on taxes or making notes for something I wanted to write). But now my body demanded total peace and quiet. I would lie on the couch, gazing for hours at that little Christmas tree of mine, not thinking of anything.

If I tried to read, I found I had to put down the book or magazine after only a few sentences; it was simply too much for me. In frustration, I actually threw out one of the books that I’d been given—threw it in the trash. And I’d never before in my life thrown out a book; I treasure books. But I was worried that maybe I’d never be able to enjoy reading again, which scared me. Just walking across the room exhausted me and left me panting.

Friends and family brought me food, and took care of household chores I could not handle. (My brother told me later that–just looking at me–he didn’t think I had long to live. To him, I just looked like someone getting nearer to death.) My friend Keith Anderson was a saint, helping me any way he could, even if I was hardly good company. He and my brother helped make my home as safe as possible, installing smoke detectors, extra night lights, grab bars for me to use in the shower and tub, and so on.

I found I needed—for the first time in my life–to nap several times a day, every day. Doctors told me to listen to my body, which had suffered damage. And to simply sleep when I needed to, using a newly prescribed bi-pap machine to efficiently force air into my lungs when I slept. I dozed a lot.

Doctors still could not figure out what caused me to have so many clots—although they were sure that spending so much of my life sitting at a desk hadn’t helped–nor could they figure out why I was also so anemic. My cardiologist commented: “Being on blood thinners and also being anemic is not a good combination.” But the reason for the anemia baffled the doctors. (It still baffles them.)

They weighed the pros and cons of possibly trying to remove some of the clots in my chest surgically—a high-risk procedure. (Just opening up my chest could jostle some clots to start moving, perhaps causing a heart attack or stroke.) I did not want surgery.

As for my future, all doctors could really say came down to something like this: We’ll just have to see, we have to take things one day at a time. They acknowledged that people who’ve had pulmonary embolisms with syncope (losing consciousness), as I’d had, tended to have a shorter life expectancy than the average person. And people with congestive heart failure, as I’d also been told I had, also had a shortened life expectancy. But each individual, the doctors liked to stress, is different.

The clots, doctors told me, had caused part of my lungs to die. Damaged lungs, I was told, often tended to get worse over time. And blood clots impeding circulation had forced my heart to work harder. Such situations tended to make the heart weaker, and if the weakened heart then had to work even harder to keep up, it could get weaker yet, and so on. (And I was told that pushing myself too hard, forcing my heart to work too hard, was risky.) The weakened heart would cause fluids to build up in my body (including my lungs, causing more breathing problems). The edema in my legs was a reflection of heart issues. All told, I was looking at some rather difficult challenges. Different doctors offered different opinions as to what my best course of action might be.

I learned to accept that there are limits to what doctors know or can do. I sought to navigate, as best I could, my own path towards recovery.

In my opinion, the best single piece of advice any doctor gave me, though, was to see if I could simply walk five steps more each day than I’d walked the day before. (They had a little device on me that monitored my heart-rate and breathing, and recorded how many steps I took.) The doctor said: “If you can walk a total of 50 steps today, try for 55 steps tomorrow.” I liked that challenge. I liked keeping track of how many steps I could take each day, and how long it took me to make them. And I liked seeing if, over time, I could gradually improve my quality of life that way.

* * *

I felt I’d accomplished something the first time I walked, using a cane, from my home to my car and back. But that little walk, which normally should have taken just a few minutes, took a full half hour now because I had to stop so frequently and rest so long to catch my breath before I could continue.

I felt proud, too, the first time I managed to make it to the market myself; but going there and buying food took more out of me than I realized. When I reached the checkout counter with my little bag of groceries, the gal asked me, “Do you want me to call 911 for you?” Startled, I asked her, “What do you mean?” She said, “You’re having such difficulty breathing. And you don’t look right.” I insisted I’d be fine; I just needed some time to catch my breath, I said. She made me sit down and rest, and gave me water to sip.

All my life, I’d loved to swim. I’d grown up on a little lake, and always felt at home in the water. But I just didn’t have the strength for it now. If I swam even a little bit—for, say, ten or15 minutes—I’d feel so exhausted and oxygen depleted, I’d fall asleep. Or be too dazed and light-headed to do anything.

* * *

As the months passed, though, little by little I gradually noticed some signs of improvement to my health. I had the energy to do some reading once again, and listen to music. On a good day, I could write for about an hour. I couldn’t write for a full day—after about an hour’s work I need to lie down and nap or I’d fall asleep at my desk. But I was grateful for that hour.

The late Broadway star Carol Channing (1921-2019)—who was such a wonderful friend and mentor to me for so many years–used to tell me, “You and I are meant to work, Chip. Create something every day. Creating helps us to become whole and well.” She instilled in me a terrific work ethic. As I rested, I could still hear her words echoing in my mind: “Create something every day….” I remembered her quietly battling cancer, and not letting it stop her from doing the work she loved. I took inspiration from her. I thought: If Carol could do a national tour while fighting cancer, I’m not going to let my health problems get the best of me now.

CHIP DEFFAA AND CAROL CHANNING

And for me, writing even for an hour now, when I was able to do that, felt good.

I read a biography of L. Frank Baum, author of The Wizard of Oz. It said that late in his life, due to terminal heart troubles, he was only able to write for an hour a day. The remainder of the day, he needed to rest. (And boy, when I read that passage, I sure “got” that!) But he managed to complete his final book—the darkest of all of his books–even under such conditions.

And I began writing a new script, even if at first I could write for no more than one hour a day. (Completing the first draft of that script, which ordinarily might have taken a couple of months, wound up taking a full year; but I was glad to be able to create. That drive to create is very strong in me.) And I tried, over time, to gradually increase my work hours.

I found I could only do one significant thing per day, though. I could, say, go to the market or I could write for an hour or so, but I couldn’t do both in one day. Because my energy was so limited, I had to choose carefully my main activity for each day. A visit to a nearby doctor might be the one thing I could do that particular day. Or going with my sister or a friend for a good walk (which ended whenever I reached the point where I started moaning uncontrollably and knew I was done for the day). My body needed a lot of “down” time to recover from any activity.

And in some way I can’t quite explain, I was now aware of my heart in an unsettling way I’d never been before; it somehow felt different and seemed to call attention to itself. I was now all-too-aware of it working. I felt it beating away as if it was working harder and a little more insistently than before, and sometimes it didn’t want to calm down, even when I was resting. Couldn’t always get it to relax. (It reminded me of the way my old car’s engine had begun to run rougher and louder before it finally died; it still ran but was clearly having a harder time.) I knew—although I still didn’t want to accept it–that I’d changed significantly this year.

* * *

Before all of these health problems, I could go into New York City any time I wanted, stay as long as I wanted. If I were rehearsing or presenting a play, I’d be in the city day after day, week after week, relishing the work. But now, I found that a trip into the city, for any purpose, used up my energy for the whole week.

If I scheduled even the shortest possible recording session—just recording one singer for an hour or two—I could manage to get through the session OK (using a rescue-inhaler to help me breathe). But I’d really struggle to stay awake driving back from the recording studio in Astoria to my home in New Jersey; by then my body was deeply craving sleep. Once I got home, I was spent. I’d lie down on top of my bed and would fall asleep before I even had time to take off my eyeglasses or turn off the lights.

I’d need to rest in bed for a week before I’d recover my strength fully so that I could make another trip into New York. If I had to be in New York for something that took more than a few hours—like, say, to have a needed procedure done at New York Presbyterian/Columbia Medical Center—I’d have to have someone drive me there and back. It just took too much out of me. And when my energy was gone, it was gone. I’d suddenly just have nothing left and be in this sort of negative state.

I’d never been through anything like this in my life. And my various doctors offered varying advice. Some doctors were cautioning me not to push things too much, but to generally do less and rest more, accept the changes that I was experiencing as permanent, and start thinking of myself as “retired.”

But others were saying that I could only discover what I was capable of doing by trying. One said it was good for me to test my limits. I liked his advice more. I’m simply not the “retirement” type. I never want to “retire,” if I can avoid it, If I can possibly keep working, even part-time, that makes me feel well.

* * *

The first trip I made into New York City, after the pulmonary embolisms, was not for work, though; it was to see Betty Buckley and Jason Robert Brown give a concert together at the club SubCulture. I knew it would be good medicine for me. I’ve always enjoyed both of them. Betty Buckley had been the last performer I saw “live” before my health problems. My friend Victoria Leacock Hoffman and I had gone to see her in the national tour of Hello, Dolly! We sat way down in the front of the theater—my favorite place to watch a show. And Buckley’s life-affirming rendition of “Before the Parade Passes By” had been galvanic. I never heard that song sung better. And I drew strength, as I began my recovery, from remembering her performance.

It was important to me now that the first performer I saw “live,” after coming so close to dying, would be Betty Buckley. She and Brown had me laughing and crying, and clapping and cheering as I sat in the front row at SubCulture to enjoy them. They performed a song of his called “Hope,” and I needed to hear that message at that time. And I needed to experience what she could do with songs from West Side Story and from Brown’s own The Last Five Years.

But it was really too soon after the pulmonary embolisms for me to go out for a night. Just driving into the city, finding a place to park, and walking to the club on Bleecker Street was almost more than I could handle. I was very glad to be there and to see their show. I was very grateful to them for the joy they gave me. But my heart was beating so rapidly by night’s end and pounding so hard within my chest, it scared me, and I hurried home as quickly as possible after the last song was sung. I was glad I’d gone into the city, but I realized there were limits to what I could do.

* * *

In the months that followed, I went into the city when I could, for work. I cherished every recording session that I was able to run, as never before. Whether I drove in or tried taking a train or bus instead, it was difficult for me to go into NYC and back. But to me, when I was able to run little recording sessions it was like attending private concerts by performers I loved. And I looked forward to each session. I felt most alive there—even if I’d get winded just making the brief walk from the control room into the “live” room, where the artists recorded.

It lifted my spirits to be in the recording studio, getting to watch an artist like Natalie Douglas record “Yiddisha Nightingale” one day (with her finding more in the song than I’d realized was there); Jed Peterson record (in both Russian and English) “Russian Lullaby,” another day; Brian Letendre record “Someone Else May be there While I’m Gone”; Bobby Belfry record “How Deep is the Ocean”; and Jeff Harnar, “Say It Isn’t So.”

Little by little, I’d get singers to record numbers. I could do, at most, one short session in a week, and then need a week of recovery time. And if, as often happened, I had other obligations–if doctors said there was testing I needed to do (and they always seemed to want more tests: X-rays and MRI’s, V-Q scans, Doppler scans, stress tests, chest scans with contrast, chest scans without contrast, right-heart and left-heart catheterizations, sleep studies, lung-function tests, etc.)—weeks might pass between recording sessions. But I was really driven; I needed to do these sessions.

I believed I might not have much time left in my life, and completing the Berlin “Love Songs” album was a high priority. Some sessions were a pure joy. Seth Sikes has a wonderfully sunlit voice. So does Jack Corbin. It warmed me, just being in the studio with them as they recorded.

Jack told me, as we grabbed burgers at “Mom’s Restaurant” across the street from the recording studio in Astoria after a short session, that he was happy to see I appeared fully recovered. He did not realize he was watching me, in one afternoon, pretty much use up my energy for the whole week. Or that I was able to breathe OK for a couple of hours due to the help of a strong bronchodilator drug that could only be used sparingly or it would cause more harm than good. He was seeing me at my very best two hours of the week! I needed to rest and sleep so much just to be able to work well in New York for a couple of hours. But it did sure my heart good to see Jack. (And he has a very bright future.) I treasured days like that.

* * *

By contrast, I had to finally fire a couple of chronically difficult young singers, who I realized were just sapping my all-too-limited energy. They were talented but too often caused problems and seemed unable to ever say “I’m sorry.” They’d show up late, unprepared, argumentative, giving me endless excuses for their irresponsibility. In the past, I might have kept forgiving them, simply because they were young. But I realized now that I’d given them too many chances. I wasn’t helping them by ignoring their irresponsible behavior. And I no longer wanted to waste even a minute of my time.

Now, when one of these singers showed up still again over an hour late for his recording session, told me that he hadn’t had time to look at the song yet but declared he could start learning it in the studio now, and began rambling about why none of this was in any way his fault because he was “just so busy; you really have no idea how busy I am, Chip”… I walked him outside and told him gently that I simply couldn’t record him anymore. He was clearly “too busy” to work with me. I like people who put me high on their list of priorities. And now, I explained, we were done working together.

He flew into a rage, like a little kid throwing a tantrum. He cursed me out, saying it wasn’t fair, that he’d spent a whole hour of his time on public transportation just getting to the studio. He insisted he could still learn the song and record it today; I just needed to give him a little extra time in the studio now. He’d cleared the whole afternoon to record.

But he’d had six weeks to prepare the song and hadn’t found time to even look at it (or let me know that he wasn’t yet ready to record so we could reschedule). Studio time is expensive. And I don’t want people sight-singing in the studio; I want them to really understand the songs they’re singing; I want them to live with the songs for a while, to get a good feel for them—to care about the songs and get inside them–before we record. He went on and on about how so many people in his life were unfair to him, firing him from gigs for no reason, criticizing his attitude, telling him he was a horrible person….

By this point, though, this talented young singer had used up every ounce of good-will I once had for him. It wasn’t just that he’d kept me waiting for far too long, or that he hadn’t bothered learning the song. By now my very-limited supply of energy for the whole day was gone. And it would take me a whole week to rest up and be able to do another trip into the city.

He whined that the students and the teachers and even the principal at his school were all mean to him, and now I was being mean to him, as well. I told him: “I sorry; I just don’t have time for this.” I didn’t want to spend whatever time I had left on Earth with people who caused me such aggravation.

He was about 18—old enough to know the importance of arriving promptly, prepared, ready to work. I’d discussed all of these things with him before. He ranted until he finally sputtered out. Then he asked me quietly, almost endearingly, if I could give him a ride home in my car, so that he wouldn’t have to take the subway by himself. No, said; I couldn’t do that.

When I finally got home and lay down for some much-needed sleep, the phone rang and it was his mother—shrilly demanding that I give her “gifted son” another chance. She started telling me that everyone was unfair to her son for no reason, that he’d been fired from one show, and that the students and teachers and principal at his high school all bullied him. She said, “I could sue them all for harassment, intimidation, and bullying, and I’d win; they all treat him so badly.” She acknowledged that her son had a habit of blowing up at people if he didn’t get his way, but then added softly: “You mustn’t take it personally, Chip. Yes, he loses his temper; yes, he lashes out if he feels corned… but he’s always been like that. You just have to accept it. He’s just testing you. He does the exact same thing to his father and me. Give him another chance…..He really loves you, you know.”

I was at a loss for words. “I’m sorry, I can’t,” I said. I had too much on my mind already.

* * *

For one thing, the clots weren’t going away. Doctors told me that normally in cases like mine, blood-thinners prevent more clots from forming, and the old clots dissolve. But for unknown reasons my remaining clots weren’t going away. After six months, a year, a year-and-a-half… the number of clots hadn’t diminished. One doctor told me he believed that the doctors who’d initially treated me in the hospital had essentially “blown it—if they’d given you better care at the start, you’d be in a much better position right now.” But other doctors felt that those original doctors had done all they could; maybe genetic factors were contributing to my health situation; or maybe these remaining clots had been building up in me gradually for years and were now so old and thoroughly embedded that it was really too late to do much about them.

Some weeks I thought I might be getting a little better; some weeks, a little worse. My doctors would say things like: “You survived the period when your life was in the most acute danger—August of 2019. You were very lucky you survived. But now your condition is chronic. There’s no cure for heart failure, or for a lung that’s been seriously damaged. We manage the symptoms as best we can.” We’d periodically try different medications and such, to see what got the best results. Most of the time, though, I felt so utterly fatigued.

I’d wake up in the middle of the night and jot notes on the pad I kept next to my bed. The heading I put on the page—which I borrowed from an old Irving Berlin song I’ve long loved—was “What’ll I Do?” And I began making lists. (I always do like making lists.)

“WHAT’LL I DO?” SHEET MUSIC

The basic question I was re-visiting, night after night, was: If my time is limited, what is it I’d most like to accomplish? I eventually put more things on this ultimate to-do list than I could accomplish even if I lived to be 120 years old. But it made me feel better to at least write what my hopes and wishes were, and to see what steps I could take to help realize some of my goals.

Finishing the Berlin “Love Songs” album was on the top of my list of priorities. I still had songs I needed to get recorded for that album, and then there would be editing and mixing and mastering, and writing liner notes. After that album was done? I listed and sequenced the song titles and singers that I hoped to have on the next four albums after that one was completed, if the fates allowed me to do four more.

I also listed (and, on subsequent day, began making notes for) the next three plays that I’d like to write, if possible, and also the next book. (I should live so long!) They’re all named on that long “What’ll I Do?” wish-list. I’m never at a loss for projects to do.

* * *

Some of the other goals that I wrote down were more modest in scale but no less important to me: I knew I wanted to sing more, I wanted to walk more and swim more, and to spend more time with a few people I really liked, who brightened my life. These were goals that I was more confident I could achieve.

I’ve always loved to sing. I’m not claiming to be any great singer. I’m simply saying that singing makes me happier. I’ve kept over my desk since college days a quote from the author/adventurer Richard Halliburton, a terrific early hero of mine: “If a man does not sing while he works… there must be something wrong with the man or with the work.” I like every bit of that sentiment. (And Sondheim’s line “If I cannot fly, let me sing” had some resonance for me, too.)

I knew that singing more—and walking more, and swimming more, if I could do it—would definitely be good for my morale.

I also believed, correctly or incorrectly, that singing more (and walking more, and swimming more) could be helpful for my lungs. If I now had less lung capacity than I used to have, I wanted my lungs to be working their very best. And singing more (and walking and swimming more), I told myself, could only help my lungs.

Keep those lungs working! Strengthen ‘em!

I’m no doctor and I can’t tell you if singing more has actually benefitted my lungs in any measurable, physical ways. But singing more has definitely felt good. And I liked to imagine that all of this singing was opening up my airways, and giving me more air to work with, helping me make the most of the lungs I have.

I came to enjoy more and more the time I’d spend singing to my deer, often in the evening or late at night.

I’d feed ‘em apples and corn, and carrots, and an occasional pomegranate. And I’d sing whatever I felt like singing to them, usually vintage Tin Pan Alley songs that I’ve relished since I was young. I enjoy that very much.

CHIP DEFFAA SINGING TO HIS DEER

And you can usually tell what’s on my mind by the songs I chose on any particular day.

If I’m in an upbeat mood, maybe I’ll sing to the deer “You Gotta Start off Each Day with a Song,” “Young at Heart,” “Keep Smiling at Trouble,” “Lullaby in Ragtime,” “Flamin’ Mamie (the Surefire Vamp),” “The Puppy Song” (which I learned from David Cassidy), “Aggravatin’ Papa” (which I learned from Carol Channing), “Ain’t Misbehavin’” (which I got from George Burns), or “Some Sunny Day.”

When I’m feeling more painfully aware of my own mortality—as often happens–I’ll sing some of the darker songs in my repertoire: “St. James Infirmary,” “I Gotta Right to Sing the Blues,” “Nobody Knows You When You’re Down and Out,” “That Dying Rag,” “A Hundred Years from Today,” and “For All We Know (We May Never Meet Again).” The deer seem happy enough no matter what I sing, so long as I bring them apples.

I’m grateful, too, when I get a chance to sing in public. I was delighted, for example, when jazz sax player/bandleader Carol Sudhalter invited me to sing a jaunty old Eddie Cantor favorite, “Ma! He’s Making Eyes at Me,” in one of her jazz concerts, presented by the Louis Armstrong Foundation. (And it was a treat having her improvise cute responses to my lines on baritone sax.) I had such a good time, I returned in subsequent months to sing (with Keith Anderson) Ted Lewis’ “I Like You Best of All” and Cole Porter’s “Let’s Misbehave,” and join the one-and-only Jon Peterson (the star of my show George M. Cohan Tonight!) in a Cohan medley; I’ve loved Cohan’s music since I was nine. I had great fun, too, singing “Way Down Yonder in New Orleans” (which I learned as a kid from an old Al Jolson record) one night at Birdland Jazz Club with a couple of Jolson’s relatives in the audience, cheering me on.

I added one more thing to my to-do list: I wanted to record an album of the songs I love to sing. I made a few trips into the recording studio cautiously, to see what I could do with my limited energy and limiting breath supply. The first song I recorded was an easy one I always love to sing, “Lullaby in Ragtime.” It brought good memories of my sister and me hearing this as kids for the first time when we saw the movie The Five Pennies (starring Danny Kaye) at the Oritani Theater in Hackensack, New Jersey. The session went well, I thought. And there was one good omen, which I thought augured well for the project. When I told violinist Andy Stein I’d picked a song that I’ve always loved but didn’t expect him to know—almost no one seems to know it—called “Lullaby in Ragtime,” he began so sing it. (That sure surprised me!) He explained that as a boy he’d gone to summer camp with Deena Kaye, the daughter of Danny Kaye, who introduced that song back then, and Sylvia Fine, who wrote it. And both parents not only came to the camp for a visit, Danny had entertained the kids. Small world!

The next time I made it out to the studio—trying to be optimistic—I gave “Keep Your Sunny Side Up” a try. I got home pleasantly exhausted—these trips took so much out of me–but really glad to be doing this. I continue to work on that album, as time permits, hoping to bring it out later this year.

CHIP DEFFAA IN THE RECORDING STUDIO (Photo credit: Jonathan M. Smith)

* * *

By this point, I should note, the pandemic was in full force. My pulmonologist was OK with me doing occasional recording sessions, so long as there were no more than a couple of people present and we were following facial-masking and social-distancing protocols in the studio. But too many of his patients were getting infected with Covid-19, he said; and some were dying from it.

He didn’t want me going anywhere indoors where groups of people were gathered–no clubs, concert halls, restaurants or theaters for me. No parties or family reunions. No big recording sessions with lots of singers. Stay home, stay isolated, as much as possible.

My pulmonologist stressed that my number-one goal now had to be avoiding the Covid-19 virus. He said my heart and lung problems made me much more vulnerable to the virus than the average person would be; if I caught Covid-19, he said flatly, it would kill me.

At first I wasn’t too good about following his guidance; but when friends of mine began dying of Covid-19, I heeded his warnings. Singer/actor Chris Trousdale, whom I thought the world of and had hoped to record for the Berlin project, was one of the first people I knew who succumbed to Covid-19. I can look up from my desk as I type these words and see a framed photo I took of him; he looks so vibrant and joyous and filled with life. (I’m also remembering him sitting next to me, enjoying one of my plays; the show got terrific reviews but it meant far more to me that he liked it than what the critics said.) A beautiful singer and beautiful person, Chris was just 34 when he passed away; I spoke at the virtual memorial service we held for him.

And in 2019-2020, two other younger friends who were important to me, Justin Eisbrenner and Josh Geyer, also died unexpectedly, reminding me further of how fragile life is.

* * *

The pandemic forced the recording studio to shut down for about five months. And even after it re-opened, I sometimes had to postpone or cancel planned sessions for the Irving Berlin project because people were testing positive for Covid-19—singers, my music director, my recording engineers. There were other times when singers were available but I was not. (There were a couple of singers I work with who were so reliable, so dependable—like Matt Nardozzi, Jon Peterson, and Seth Sikes–I could let them record even if I wasn’t able to make it to the studio myself. I knew they’d arrive fully prepared, would do their best, and I’d be happy with the results. I’m grateful to them for recording, a time or two, when I couldn’t make it to the studio myself. No one makes my life easier than those artists! But as a producer I generally much prefer being there–watching, adding input, making sure we’re getting the best possible take.)

Some people I really wanted for the Berlin project had to postpone repeatedly for one reason or another. Sometimes they were just nervous about going out during the pandemic. I was happy to wait for them, however long it held things up.

But rather than let available studio time go to waste, I began also recording some other singers for a projected album of gay love songs, “My Man.” And it made me happy to record such pros as Lee Roy Reams, Sidney Myer, Luis Villabon, Luka Fric, Magnus Tonning Riis and more for that album, which is being released now.