IN SEARCH OF LOST IRVING BERLIN THEATER SONGS…

The deeper I got into researching Irving Berlin’s life and music, the more intrigued I became by the many songs this musical genius wrote for shows that wound up getting cut, forgotten, or lost. Finding, hearing, and recording these long-lost rarities became a mission for me….

By CHIP DEFFAA

Chip Deffaa with some of his Irving Berlin sheet music and memorabilia

Over the years, I’ve produced more recordings of Irving Berlin songs than anyone living. I’ve released 15 albums dealing with Berlin’s music, with more to come. I’ve enjoyed getting great musical-theater artists, like Betty Buckley, Anita Gillette, and Stephen Bogardus to perform Berlin’s best-known songs. (And fans keep requesting those beloved, oft-recorded songs.) But I’ve gotten an even bigger kick out of bringing to light some of the songwriter’s “unknown” works. Songs that, for one reason or another, may have been forgotten or lost. For me, searching for such lost songs is fun.

Theater-music aficionados will ask me: “Where in the world do you find these lost Berlin show tunes? And how could any music by a master songwriter like Berlin ever get lost in the first place?” I’d like to answer those good questions. My latest album, “Chip Deffaa’s Rare and Unrecorded Irving Berlin Songs” (available from Amazon, Ebay, Apple Music, etc.), includes—as do almost all of the Berlin albums I’ve produced—some vintage rarities that will be brand new to listeners.

One sheet-music collector, justifiably proud of his large Berlin collection, wrote me: “I’m fascinated by two never-before-recorded Berlin songs on your album that were totally unknown to me—’Angelo’ and ‘It Can’t be Did’–which I understand were written for a Broadway show called ‘Jumping Jupiter.’ Where did you find these songs? I’ve never come across any published sheet music for them.”

Well, the reason that collector has never seen any published sheet music for those two songs is that Berlin—quite deliberately–never made such sheet music available to the public. He wrote those songs for the exclusive use of one star–a vaudeville and Broadway performer, active professionally from the 1890s into the 1930s, named Lillian Shaw (1876-1978). According to her New York Times obituary, she appeared in the Ziegfeld Follies and Ziegfeld Midnight Frolic, among other shows. In her later years, she was a member of the Ziegfeld Club (for Ziegfeld alumni), and enjoyed reminiscing about her years in show business.

She saved, all of her life, her typed pages of the lyrics for “Angelo” and “It Can’t be Did,” which she apparently performed both on Broadway in “Jumping Jupiter” and in vaudeville, and she also saved her signed contract with Berlin (from 1909) indicating that Berlin created the songs exclusively for her. Because the material was hers alone—you could only hear those songs if you went to see her performing in person—no sheet music was ever published or made available to anyone else. She did not want any would-be competitors stealing her stuff! Berlin loved writing for specific performers and took such contractual agreements quite seriously. (He got angry with Fanny Brice, for example, when Brice generously let Lillian Shaw use material Berlin had written exclusively for Brice!)

Lillian Shaw rose to fame by singing songs “in character”—portraying, at different times, Jewish, German, Italian, and French women. She claimed to be the first such character-performer. “Angelo,” for example, was written to be performed with an Italian accent.

That the songs “Angelo” and “It Can’t Be Did” have survived at all is something of a miracle. Whatever musical orchestrations once existed for those songs (for use on Broadway or in vaudeville) appear to have been lost over the years. But fortunately, Shaw, who lived to be 102 years old, carefully saved the typed pages of lyrics for those songs. After her death, some of those pages wound up in the possession of one private collector; others wound up in the possession of another collector. Berlin himself saved only the skimpiest of partial vocal lead sheets for those songs—no piano parts–indicating which notes went with which words.

I gathered together the various lyrics that had survived, and the partial lead sheets that Berlin had kept. I turned this material over to pianist/arranger Richard Danley, who’s worked as my primary music director for nearly 20 years. Combining material from all three sources, Richard was able to write out the arrangements of the songs that we recorded. Veteran Broadway and cabaret pro Joan Jaffe–an expert in such matters, with terrific comic timing–handled with aplomb the Italian dialect song “Angelo.” And thus, the song could be heard for the first time in well over a hundred years!

I asked Samantha Cunha to record a rendition of “It Couldn’t be Did,” explaining that I was sorry I couldn’t offer any kind of context-setting information on that particular song. All who’d known this song have passed on. We puzzled over one line in the lyrics that was typed out as follows: “You’re a dumb kop.” Was the character in the song calling her fellow a dumb “cop” (a policeman)? Or did Berlin mean “dummkopf” (a German word suggesting stupidity). I’m guessing the latter—especially since Shaw sometimes did German characterizations. But we’ll never know for certain.

Berlin, incidentally, could not write music. He could play piano—not too well, and in only one key. He would play, sing, and hum songs that he created, which a musical secretary would then take down and put into written form for him. The typed lyrics that Shaw saved (with the words “you’re a dumb kop”) may have been typed by Berlin himself or may have been dictated by Berlin to a musical secretary.

In any event, the songs “Angelo” and “It Can’t Be Did” have survived only because Lillian Shaw happened to be a “saver.” By contrast, Shaw’s good friend, Fanny Brice, for whom Berlin also wrote special material, was not a “saver.” And some warmly received material that Berlin wrote especially for Brice—for which I’ve long searched in vain—appears to be lost for good. (But then again, you never know what might eventually turn up some place; sometimes it takes years to find things. And things get mis-filed. I found one very valuable Brice item, by accident, in the Comden & Green files at Lincoln Center.)

In 1909, when Berlin wrote “Angelo” and “It Can’t be Did,” he was just 21. Those two songs—quite rough around the edges—capture a songwriter near the very start of his career, still in a formative stage, still finding himself. They’re certainly not masterpieces. But I like seeing artists’ early work. I like seeing the way an artist’s skills may improve over time. And Berlin’s abilities improved with astonishing rapidity.

* * *

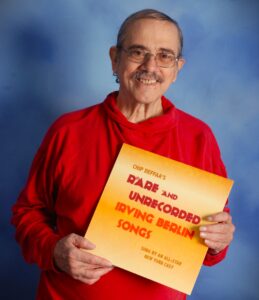

Chip Deffaa with his latest Irving Berlin CD

Very good songs may wind up getting lost, in whole or in part, for all kinds of reasons. Berlin was extraordinarily prolific. He wrote some 1200 songs that we know of–and thousands of other songs, he said, that he simply discarded altogether because he didn’t think they were good enough.

Berlin was the most successful songwriter of his time—he wrote more hits and made more money than any of his contemporaries—and he certainly gave us an abundance of riches. Berlin created full scores for 18 Broadway musicals and contributed individual songs to assorted other shows.

Sometimes excellent songs wound up getting cut from shows during out-of-town tryouts or previews simply because the show was running too long. Or the songs didn’t quite seem to fit the tone of the show as it evolved.

A case in point. When Berlin was writing his great musical “Call Me Madam” (1950), he wrote a serious anthem for its star, Ethel Merman, to sing called “Free.” It was a song to remind us how lucky we Americans are to enjoy freedoms that people in many parts of the world do not have. It reflected Berlin’s deeply felt patriotism, and was written when Cold War tensions were high.

Merman introduced “Free” during out-of-town tryouts. It was a well-crafted song, but too solemn and preachy for an essentially light-hearted musical comedy like “Call Me Madam.” It seemed out of place, and slowed down the show. Berlin reluctantly but wisely cut the song from the show. (The cheery new song that he quickly created as a replacement for “Free”–the irresistible “You’re Just in Love”—turned out to be a tremendous success for both Berlin and Merman, becoming the high point of the show.)

Berlin liked “Free.” It was a good song. But didn’t know quite what to do with it. Four years later, when he was creating the score for his film musical “White Christmas” (1954), he took the melody that he’d written for “Free,” wrote totally new lyrics, and turned the song “Free” into the song “Snow.” I think the long-forgotten “lost” song, “Free”—written with greater conviction– is superior to the rather innocuous “Snow” (which basically tells us that snow is pretty). But on my album “Chip Deffaa’s Rare and Unrecorded Irving Berlin Songs,” you can hear cabaret star Ann Kittredge, accompanied by Alex Rybeck, masterfully sing both songs that share the same melody—the “lost” one (“Free”) and the well-known one (“Snow”)–and you can decide for yourself which one you prefer. Kittredge does a wonderful job. My jaw dropped, just listening to her in the recording studio as she and Alex Rybeck brought “Free” back to life.

Here’s another intriguing “lost” song. In 1920, Berlin wrote a lovely number for the Ziegfeld Follies called “The Girl of Your Dreams.” Ziegfeld liked the song. But he also felt there’d be greater opportunities for staging the song in typical Ziegfeld fashion if Berlin revised it so that it no longer was about a man thinking of his one ideal girl, but a man thinking of all different girls. Ziegfeld got Berlin to revamp the song. The song originally called “The Girl of Your Dreams” became “The Girls of My Dreams.”

And now Ziegfeld could have a bevy of his statuesque showgirls parade across the stage while tenor John Steel sang their praises, repeating the formula Ziegfeld had so successfully employed the previous season with Berlin’s “A Pretty Girl is Like a Melody.” John Steel’s recording of “The Girls of My Dreams” became a hit. The original version of the song, “The Girl of Your Dreams,” was forgotten.

I asked Eric William Morris, costar of the Broadway musical “King Kong” and of the world-premiere production of “Be More Chill,” to sing both songs—the “lost” one and its replacement, both sharing the same melody. And his superb performance opens the “Rare and Unrecorded Irving Berlin” album. (Morris, I might add, really has a flair for songs of this era. I just love his singing. And I also had him record a never-before-recorded Cohan song, “I’m a One-Girl Man,” and the better-known song it was eventually turned into, “My Town,” for my album “The George M. Cohan Songbook.” And I’ve found more forgotten rarities for him to present on future albums. I can’t wait to get him back in the studio again.)

Some Berlin songs became “lost”—or almost became lost—due to his own insecurity. He wrote songs constantly, but was not always the best judge of their quality. If he tried out a new song before other people who didn’t seem too enthusiastic, he’d sometimes give up on the song right away.

When Berlin wrote “There’s No Business Like Show Business” for “Annie Get Your Gun,” he sang it for his colleagues working on the show. He felt the song hadn’t really gone over too well with them. When he got back to his office, he threw out his only copy of “There’s No Business Like Show Business.” The song only survived because his secretary—who sensed its worth much better than Berlin did–retrieved the crumpled pages from the waste basket. The song, of course, eventually became one of the biggest successes of Berlin’s career.

And when “Annie Get Your Gun” went into rehearsals, everyone in the cast loved “There’s No Business Like Show Business” so much, even Berlin began to suspect he might have a hit. He thus dropped from the show one song, “Take it in Your Stride” that he’d written especially for Merman, to make room for a reprise of “There’s No Business Like Show Business.” “Take it in Your Stride” went back into Berlin’s trunk, and was forgotten. (I’ve recently found a copy of this unpublished song, along with additional “cut” material from “Annie Get Your Gun,” that I plan to include on a future album of Berlin rarities.)

Cole Porter—one of the greatest of all songwriters—always insisted that one of the best songs Berlin ever wrote, a lifelong favorite of Porter’s, was one that Porter was unable to persuade Berlin to publish. Berlin played it and sang it for Porter, who was so taken with it, he memorized it and often played and sang it for others. It’s a wonderful song, and I’m going to have one of the finest singers I know sing it on a forthcoming album. But Berlin, for whatever reason, never felt it was good enough to publish. And it remains an “unknown” song as far as the general public is concerned. Berlin just didn’t have confidence in it. Maybe that seems strange. But don’t forget that “God Bless America”—one of Berlin’s most enduringly popular songs—was actually first written by Berlin back in 1917. But he worried it was too blatant in its sentiments. And the song remained in his trunk—unpublished and unheard—for 21 years , until Berlin dusted it off, touched it up a bit, and let Kate Smith introduce it on radio. No one was more surprised than Berlin at how extraordinarily popular this song—which could easily have remained forever in the “lost” category—became.

* * *

I’m a collector by nature—vintage recordings, sheet music, showbiz memorabilia. I’ve got one of the two largest privately-held collections of George M. Cohan sheet music in the world. And I have a pretty good collection of Berlin music. When I was growing up, it was easy to find inexpensive vintage sheet music in second-hand shops and thrift stores.

If I’m searching for a song today, the two best finders and suppliers of sheet music out there are Stephanie Rinaldo (Hollywood Sheet Music) and Michael Lavine (Michael Lavine Music). Both Rinaldo and Lavine have extraordinary sheet-music collections. (And, equally important, know other important collectors.) And both will go above and beyond the call of duty to search for desired items they may not have. Both have been terrifically helpful to me over the years, finding rare items I’d not been able to find on their own. I’m in their debt. And various friends have also searched on my behalf in places like the Lincoln Center Performing Arts Library and the Museum of the City of New York. Or have been helpful to me in one way or another, more than they may realize, and I’m very grateful. (Thank you, Ian B!)

However, some songs prove almost impossible to find. Irving Berlin was far better than most people when it came to saving copies of his work. But in his exceptionally long career, Berlin created more music, and more variations of that music, than can be imagined. It proved impossible for him to save and store everything.

Sometimes a song would be written in a longer form for use in a Broadway show, but then published in a shorter, simpler form for average Americans who simply wanted to be able to play and sing the song on a piano at home. And over the years, the longer original versions sometimes would get lost. Searching for the longer original versions is not always easy. Let me give you two examples.

I’ve long been searching for a complete version of a catchy song called “The Monkey Doodle Doo” that Berlin wrote for the Marx Brothers’ 1925 Broadway hit “The Cocoanuts.” Berlin saved among his papers the lyrics for a “patter section” of this song that was omitted in the published sheet music. (And I liked those lyrics a lot.) But I’ve not been able to find the music for this patter section anywhere. I’ve listened to all available recordings of this song; all omit the patter section. I watched the film adaptation of “The Cocoanuts,” but the patter section is not there, either. Nor was it included the 1996 Off-Broadway revival of “The Cocoanuts.” Nor was it included in a rare 1925 dance-band arrangement that Vince Giordano and his Nighthawks Orchestra still play with great zest today.

The indefatigable Stephanie Rinaldo—bless her!–has searched for this lost “patter section” music everywhere she could, too, from reaching out to people she knows in collector circles to getting the Library of Congress to search its holdings. I was so excited when Stephanie Emailed me the other day that it appeared the Library of Congress just might have the missing music. They’d found something! As soon as I received a copy of the original handwritten lead sheet marked “The Monkey Doodle Doo,” I brought it to my music director, pianist Richard Danley. He tried so hard to see if the lyrics of the patter section might fit this melody. But they did not! Not even close! (How we tried to make the words and music fit together, in the recording studio this week.) And so, for that intriguing song, the mystery of the missing music remains.

Sometimes it takes years to find “lost” music. One of my favorites of all Irving Berlin songs is an infectiously rhythmic number—quite ahead of its time—called “Everybody Step.” It was introduced by the Brox Sisters in “The Music Box Revue of 1921.” And Berlin’s papers included a typed version of the lyrics, preserving the words that were sung in “The Music Box Revue.” And these typed lyrics for “Everybody Step” included a clever “patter section” that was omitted from the shorter, simpler published sheet music, and from the popular recordings of the song.

Try as I might, I could not find any surviving music for the patter section of this song. It seemed exactly like the situation with “The Monkey Doodle Doo.” And yet I was dogged by a faint feeling that I’d once seen or heard the music to this patter section somewhere. (I couldn’t quite remember just where.) But I could not find the music for the patter section. It appeared to be lost forever.

I hated the idea of leaving this wonderful “patter section” out of the song. I wanted to include the song in a show about Berlin that I wrote and directed, “Irving Berlin’s America.” And so, as we developed the show, I told the actors who performed this song to simply chant the lines for which the music had been lost, treating the “patter section” almost like rap. Audiences accepted our approach. And we did it that way—chanting the lines without music–on cast recordings, with Matt Nardozzi and Giuseppe Bausilio.

But still I was haunted by the faint feeling that I’d seen or heard the music to this lost “patter section” at some time. But where? I couldn’t figure that out, and I turned my attention to other projects.

I’m always working on several things at once—writing a play or a book, producing albums. And I try to accommodate any requests or suggestions I get for songs to include on albums. For example, a future Berlin album is going to include a fresh recording of a fine, little-known Berlin song, “This Year’s Kisses,” simply because a playwright/screenwriter I admire, Sherman Yellen, likes that song. And I’m working extra hard to fulfill a request, on the next album, made by Thomas James Hill. (He’s a good guy and deserves a song to let him know he’s been heard; that’s my tale, and I’m sticking to it.)

And then one fellow, Stuart Wade, who likes the historic-reissue albums I’ve produced (with rare recordings from my collection by George M. Cohan, Fanny Brice, and Al Jolson), asked if I could produce a CD of Al Jolson singing Irving Berlin songs. And so, in my spare time, over a period of months, I listened to all sorts of vintage Jolson and Jolson-connected studio recordings and airchecks of live radio performances. I’d actually long thought an album of Jolson singing Berlin songs could be fun, and this fellow’s request gave me an excuse to listen to some rare, half-forgotten material in my collection that I had not listened to in years.

And then I found it—an aircheck I’d owned for years but had pretty much forgotten about! A “live” radio broadcast from the 1930s. And Al Jolson is introducing the Brox Sisters, to have them sing once more a number that they’d sung on Broadway in “The Music Box Revue of 1921” but had never recorded—“Everybody Step.” And they swIng easily into a song they’d sung for more than 400 performances back in 1921-22, just the way they’d done it back then—including the long-lost patter section. I included this charming performance on the CD I put out, “Al Jolson Sings Irving Berlin.”

I still have never found any written music for that great patter section. Things do get lost over time–even sections of first-rate songs like “Everybody Step,” one of Berlin’s masterpieces. But because someone recorded that “live” 1930s radio performance by the Brox Sisters, the melody of the lost patter-section can be heard.

I’m going to have Richard Danley transcribe the music from that “live” performance so we can prepare a proper chart—perhaps the only one existence—of the complete song, “Everybody Step,” so that we can record it in full, just as Berlin conceived it.

A lovely article by a brilliant, deeply committed scholar of the Great American Song Book. He has brought to life so much nearly lost richness—jewels and more jewels. Those who love the music love Chip Deffaa.