On The Town … With Chip Deffaa … April 4, 2014

Boy! This past week or so has given me some extraordinary memories. I’d like to share a bit of what I’ve witnessed of late on stage in various places, from performers both young and old.

First. I sure felt the spirit of the late Jonathan Larson strongly at the Trumbull (Connecticut) High School’s production of his musical Rent. This was the school, you may recall, where the principal tried to cancel the students’ production of Rent, and the students protested successfully for weeks until they won the right to do the show. Perhaps the fact that they had to fight so hard to do the show gave them an extra investment in it. But they pulled it off well.

Jonathan Larson |

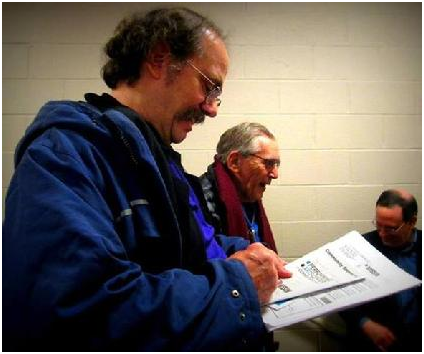

Al Larson, father of Jonathan, greets cast of Rent |

As I begin typing this column, I’ve just gotten back from attending their opening night. And it was about as emotion-rich an opening night as any I’ve attended, anywhere, in many years. Astonishing, in various ways! Jonathan Larson’s parents, Al and Nan, were there. (And it was wonderful to see them again!) And his sister, Julie, was there. (Such good vibes in the room.) And his best friend from childhood, Matt O’Grady, and his friend and former roommate, Jonathan Burkhardt (a successful filmmaker today). And singer/songwriter/actress Julia Santana, who for three years co-starred as “Mimi” in the national tour of Rent, and other special guests. It was an extraordinary meeting of older people who’d loved Jonathan Larson… and younger performer who were not even born yet, back when Jonathan Larson first began writing Rent. And the young actors got well into his spirit in this production. Rent is not an easy show to perform, but they presented it with love and understanding. Their huge cast included 39 singing actors. Rent is ordinarily performed with a cast of 15. I loved hearing all of those extra voices soaring on Larson’s extraordinary, hope-filled ensemble numbers. For me, the best moments of that show have always touched me deeply; to me, there’s something profound and meaningful there; spiritual.

Julia Santana, Chip Deffaa, Larissa Mark backstage at Rent Julia Santana, Chip Deffaa, Larissa Mark backstage at Rent |

Chip Deffaa, Al Larson at Rent. Photo by Julia Santana |

It was rewarding watching the show–and then exhilarating meeting afterwards with the cast and crew–everyone really was on cloud nine. I’m sure that Matt Buckwald–who did an exceptional job playing “Angel”; what a fine actor!–spoke for many of his castmates when he noted afterwards: “This was definitely one of the best days of my life. There are no words right now for how grateful I am to be in this production. Such important people came to share their love with us, and it was so overwhelming. Today will stick with me for the rest of my life.” I felt the same way, being backstage after the show, sharing in the celebration with cast members, and friends and family of Jonathan Larson. As one of my nieces would say: So many feelings.

I was not expecting the event to be nearly so emotional. I’ve seen Rent many times, many places, going back to the very beginning; I know the show inside-out. I saw it at the New York Theater Workshop in the East Village, where it was first developed; I saw it repeatedly on Broadway (introducing my nieces to it–one of whom, Alexandrah, has now seen it more than 30 times!); I was delighted to attend the recording session for the original Broadway cast album; I caught the national tour when the show played the New Jersey Performing Arts Center; the Off-Broadway production at New World Stages; I caught miscellaneous productions at the Triarts Sharon Playhouse in Sharon, Connecticut, the Westchester Broadway dinner theater in Elmsford, New York; the Rosen Theater in Wayne, New Jersey; and I’ve also attended special events (like the fifth anniversary celebration) in connection with the show. Friends of mine were in the show on Broadway, and helped Jonathan Larson make his demo recordings. Other friends of mine were in the first staged reading of the show, several years before the first production. (I sat with one of them, Karen Oberlin–who played “Maureen” in the original reading–when Rent opened at New York Theater Workshop. She later helped me, hosting a little tribute to Jonathan Larson that I organized after he died.)

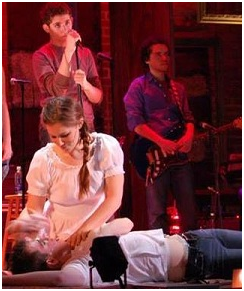

A scene from Rent at Trumbull High School, Trumbull, CT

When the Trumbull High School principal, last November, cancelled the proposed production of Rent as the school’s spring musical, I was disheartened. I’d seen this sort of thing happen before, elsewhere. And, as a theater professional, I’d written letters of support for kids before. I do that as a matter of course. I wrote letters, for example, when there were controversies at Connecticut’s Amity High School over doing Sweeney Todd and at Waterbury Arts Magnet High School, over doing August Wilson’s Joe Turner’s Come and Gone, and at Corona Del Mars (CA) High School over doing Rent. (And there are always more schools cancelling plays out of fear of controversy.) Such letters often fell on deaf ears. Administrators who’ve decided to cancel shows do not usually back down. Often they are scared of offending anybody. (But great theater often will offend somebody. While we were driving up to Trumbull in my car, Julia Santana recalled doing Rent all across the US, from 1997-2000; the show was embraced wholeheartedly in big cities like Los Angeles, but it was not always accepted by everyone in less sophisticated places, and Santana heard it–and how!–from some audience members who did not approve of the show. There were blue-haired ladies who shouted their disapproval.)

The Trumbull High School principal said the same sorts of things, in cancelling the show, that I’d heard elsewhere–saying that he believed Rent was too “controversial” and included themes inappropriate for high-school students to deal with; he felt this was not “the time or place” to do Rent.

And for weeks the students–led by Larissa Mark, president of school’s drama club (“The Thespians”)–protested what they perceived as unfair censorship. Larissa Mark and her fellow students noted, correctly, that there were no subjects in Rent that students of today were not aware of. The idea that teens needed to be “protected” from knowing about supposedly controversial subjects in Rent (such as drugs and sex)

struck her and other students as absurd. Topics that had been highly controversial when Rent first opened in 1996 are part of the mainstream today, Mark argued.

Emily Ruchalski, Michael Lepore, Matt Buckwald in Rent Emily Ruchalski, Michael Lepore, Matt Buckwald in Rent |

Rent cast |

I was very sympathetic to the students’ cause from Day One. And not just due to my respect and admiration for the late Jonathan Larson–who was a genius. I hate censorship generally. (One of my own favorite high school teachers was pilloried by some parents when I was a teen, because she dared teach Mark Twain; some parents wanted to censor him because he used the “N-word” in his book.) I felt students could only benefit from exposure to Larson’s uplifting, Pulitzer Prize-winning show. Larson had a very big soul, and Rent is, ultimately, a very positive, life-affirming show. It’s about community and love, and acceptance of diversity, and making the most of life even when facing tough challenges (such as AIDS). Larson was a keen observer of life; characters in his shows make mistakes (as we all do in life); some are taking drugs (and paying a price for that decision); all are struggling to make the most of life.

Writing in this column and elsewhere, I believe I was the first writer outside of the Trumbull students’ local area to call attention to their struggles; I thought the cancelling of Rent was bigger than just some local dispute. I told Victoria Leacock Hoffman–who’d been Jonathan Larson’s girlfriend and original producer, and still remains his biggest champion today–about the cancellation of Rent. She is one of my favorite people in the whole world–idealistic and passionate and honest–and she quickly helped spread the word to the Larson family, and everyone else.

And as people who’d been close to Jonathan Larson made their voices heard, urging the high school administration to allow the students to do Rent, the students’ protests began gaining more and more attention. Writer Howard Sherman, former Executive Director of the American Theater Wing, did everything he could to spread the word, as well, and deserves a great deal of credit. My hat’s off to him. The dispute went on for weeks–with The New York Times, the Washington Post, and NPR all following the story. (I found it fascinating, incidentally, that during the same time that these protests over Rent were going on in real life up in Trumbull, Connecticut, I got to see and hear in NYC–at a New York Theatre Barn event coordinated by Producing Director Jason Najjoum–a sample of a musical that Sammy Buck is developing about people in a fictitious small town protesting a proposed production of Rent. I very much enjoyed what I saw and heard of that show, titled Small Town Story, and hope it will have a life. Buck and Najjoum, incidentally, also made it up from New York City to Trumbull to see Rent, and congratulate the kids.)

Goodspeed Opera House offered the Trumbull kids the use of their famed venue, if the kids were not permitted to do the show at their high school. I thought that was an extraordinarily generous–and appropriate–offer. The Dramatists Guild, representing the playwrights of America, wrote to the school, urging that Rent not be censored.

And by Christmastime, the Trumbull High School principal relented, finally agreeing that the students could perform Rent at the school….

Now might be a good time to introduce you, via video, to some of the kids involved. Here’s a link to one video clip prepared by students at Trumbull High School–and it is a handsomely-produced student video–documenting their production of Rent:

Among the many jobs our students took charge of, we had a team who wanted to document our production of RENT: School Edition.

Posted by THS Musicals on Saturday, March 29, 2014

The Trumbull High School principal, Marc Guarino, worked with the students, artistic director Jessica Spillane, producer Shannon Bolan, musical director Jerold Goldstein, choreographer Frank Root, technical director Matthew Bracksieck, and company to make the process of producing Rent as positive an event–and as much of a learning experience–as possible. And they succeeded. Besides doing the show itself, they had kids manning informational tables dealing with topics discussed in the show, and creating a kind of living-theater installation in the lobby, representing the Lower East Side in the time of Rent.

My compliments to Rent cast members Michael Ell, Zac Gottschall, Ava Gallo, Michael Lepore, Emily Ruchalski, Casey Walsh, Daniel Sutter, et. al. The school put 39 actors on stage (which director Jessica Spillane told me is actually a small cast for that school), with perhaps an additional 20 kids working backstage in one capacity or another. I wish I had room to print every name here. .

Victoria Leacock Hoffman–who always speaks her mind clearly–told the cast afterwards: “You were fu*king awesome!” The students roared their approval. They’ll never get a better review for work they do, anywhere, than that four-word line she uttered. And she added an AIDS-prevention message, just as Jonathan Larson might have: “Don’t do drugs! Use condoms every time!” (Rent was inspired, in part, because Jonathan Larson had lost a couple of valued friends to AIDS. The musical was, in part, a remembrance of them. And photos of them remained backstage when the show played on Broadway.) The kids, by the way, should know that if they’ve met the approval of Victoria Leacock Hoffman, they’ve done a good job. She was not only as close to Jonathan Larson as anyone, she helped produce shows of his, including the Off-Broadway production of his musical tick tick…BOOM! She wrote the introduction to the published libretto of Rent, and has directed productions of Rent. She’s seen the show hundreds of times, and if it is not done well, she is not shy about speaking up. One time, we went to a production of Rent that was not done well. At all. I don’t need to embarrass anybody by saying exactly where and when that particular production was. But afterwards, we went backstage and she spoke to everyone for perhaps an hour, telling them very clearly all the things they’d done wrong. In that painfully sterile production, no one so much as hugged or made physical contact; the director seemed to be terrified of letting a gal affectionately touch a gal or a guy affectionately touch a guy; Victoria Leacock Hoffman went through point after point in the script where some sort of physical contact, from a slight touch, to an embrace, to a kiss was called for dramatically. The whole show was about love, she stressed to that cast, several years ago; and by eliminating physical contact, the whole message of the play was undermined. She was tough–and appropriately so–on the professionals who did a bad job of mounting that particular production that we went to together, a few years ago.

Here’s one more student-produced video, hosted by Matt Buckwald (“Angel”), giving a backstage look at the production:

But everyone was smiling at the end of Trumbull’s production. The audience gave the kids a standing ovation. The “controversy” the principal had been so very much afraid of… was gone. Everyone in the audience–young and old–seemed to be accepting the show for what it was. Jonathan Larson would have loved that–seeing his show embraced not just by some hip New York theater crowd, but by ordinary people of all ages, in a suburban community not all that terribly different from the one in which he’d grown up.

I was very glad to see this sort of “happy ending” for the Trumbull, Connecticut kids who’d fought long and well–signing petitions, writing letters, talking to the press–for the right to mount the show. They did it well. They had a “wall” in the lobby on which we could leave our comments–just the way many people (myself included) left comments years ago on a wall at Broadway’s Nederlander Theater, when it was home to Rent. Julia Santana wrote an open-hearted message for the kids on the wall (“You are love…”) that seemed very Rent-ish.

I’d been in the theater at Trumbull High School once before, to see a show. And I’d actually seen some of these same Trumbull kids years before in a nearby production of Oliver that featured an actor friend of mine, Peter Charney (who also drove up with us to see Rent in Trumbull). I was glad, for many reasons, to be there. And I was proud and happy that the Dramatists Guild, to which I belong, gave Larissa Mark a special award, for her fight to present Rent.

I suspect that the theater program at Trumbull High School will be moving forward with a new energy now–this has really been an incredible experience–and the kids will do some very good things going forward. I’d love to see more of their work. (I’d love to see them do some of my work someday, for that matter.) I like seeing kids perform with belief in what they’re doing. And with passion.

Jonathan Larson was a brilliant and unusually dedicated artist. He spent seven long years developing Rent. He started the project with a collaborator, Billy Aronson, who gave up on the project pretty quickly. He doubted there was much likelihood that two young unknowns like themselves could get a musical for 15 or more actors professionally produced; why keep tilting at windmills? But Jonathan Larson–who had great belief in the project–continued on his own, writing book, music, and lyrics. And adding songs and scenes, and tossing them out, and revising and rewriting. He never really earned anything for his labors on the show. He had to work as a waiter at the Moondance Diner to pay the bills. The script evolved slowly.

He died just before it opened–just before it went on to become a huge, international phenomenon. He died, due to an aneurism, way too young. But I love the way he continues to touch lives, all of these years later. For me, it was a privilege to share this opening night with those wonderful kids, and with Jonathan Larson’s parents, his sister Julie, Victoria Leacock Hoffman, Julia Santana, Jonathan Burkhardt, Matt O’Grady…. And after I’ve finished writing this column, I’ll put on the original Broadway cast album of Rent. And revel one more time in… “La Vie Boheme”!

* * *

While we’re on the subject of good music, I’m very happy that the cast album of Jason Robert Brown’s new musical, Bridges of Madison County, has just been recorded. It’s in the process of being mixed and mastered as I type this, and I’m looking forward to it. I know that’s an album I’ll enjoy playing. Here’s a taste of what you’ll get in the show–and on that cast album: Kelli O’Hara and Steven Pasquale singing “One Second and a Million Miles.”

Have you’ve seen the show yet? I’ve seen it twice and look forward to seeing this serious, sweet/sad musical again–preferably on a night when Brown himself will conduct the show. Not that there’s anything wrong with the regular conductor. But ever since I first saw (in my youth) Leonard Bernstein conducting some of his own music, I’ve always loved seeing composers conduct their own music. And I like that Brown will from time to time surprise the audience whose come to see his new show, by conducting it. (George Gershwin, incidentally, did the same thing, with his musical Girl Crazy. He had nothing against the way Red Nichols regularly led the orchestra–he’d personally selected trumpeter/bandleader Nichols for the show; Gershwin just liked to conduct the show himself once in a while. Nichols was happy to accommodate him. And audiences no doubt felt it was a special occasion if Gershwin himself conducted.)

I recommend Bridges of Madison County (directed by Bartlett Sher)

for a couple of reasons. First, the score contains some gorgeous music, wonderfully arranged by Brown himself. The cast is impeccable. And Kelli O’Hara, in the best performance of her career–which is saying plenty– does a magnificent job. The first time I went to see the show, I ran into a distinguished Broadway actor at intermission. (Don’t ask me to drop his name; he was just a happy audience member that night.) He said to me: “As far as I’m concerned, they can stop everything and give Kelli O’Hara the Tony Award right now.” I felt essentially like that, too. She’s delivering a sublime performance.

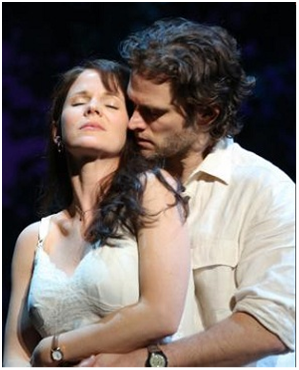

Kelli O’Hara and Steven Pasquale

The show, alas, has book problems. I hate saying that, because Marsha Norman, who wrote the libretto (and also wrote the play ‘Night, Mother, which I liked very much) has done some terrific work in the past. But this show, at times, feels a bit too slow and stately; and it feels a little long. That is not a deal-breaker for me; few musicals are perfect, and this show’s strengths far outweigh its weaknesses. I find the story–about a woman trapped in an unfulfilling marriage who finds joy in a brief affair with a stranger passing through town–intrinsically interesting, and the score and the stars are excellent. I hope the show makes it through the awards season; I’d love to see it win some important awards and hopefully gain enough momentum to keep going from there. Right now, though, it is not doing so great at the box-office. As I type this, its box-office receipts are considerably below maximum potential. Shows need to do better at the box-office to survive. (Incidentally, when I told friends, after seeing it the first time, that it contains some glorious music, but it feels a bit “long” to me, they asked me just how long it is. I want to be clear–when I say it “feels a bit long,” I’m not saying that the running time is literally longer than most shows; I’m describing a perception. My Fair Lady has a longer actual running time than many shows, but it does not “feel” long; every song, every scene, feels necessary and advances the story; the show moves well from start to finish. It’s as perfect a musical as I’ve seen. The same holds true for Fiddler on the Roof, Mame, The Music Man, Company, Chicago and any number of well-written musicals. There is no fat on these perfectly constructed shows. And you get caught up in them. Camelot has a glorious score, but its book is not quite as well constructed as that of My Fair Lady; and there are times, when I watch productions of that show, when my interest sags a bit. But the show offers plenty of rewards, despite imperfections. I felt a bit like that at this show.

Bridges is a flawed show, but it contains quality work. I might also add that the orchestra is a real pleasure to hear from beginning to end. Those fine strings! I’d love to see this show make it. And see Jason Robert Brown’s charming Honeymoon in Las Vegas (which I loved in its Paper Mill Playhouse tryout) join it on Broadway. They’re two very different shows–I think Honeymoon is perfect in its own cute, sweet way– and it’d be fun to have them both on Broadway. I’d like to see Bridges enjoy a good long run, if possible.

Incidentally, if Kelli O’Hara ever tired of the role, I think it might also be very good role for Celia Keenan-Bolger; I’d love to see her take a crack at that role some place, someday.

But right now, ticket sales are soft. The producers are borrowing funds to keep the show afloat. I hope Bridges of Madison County can hang in there. In the mean time, if you’re curious to see the show, the good news is that you can find tickets at a discount. I’m looking forward to seeing it again. And as I type this, I am hearing in my head one song from the show, “When I Cross Over.”

If I had extra cash to invest in Broadway shows, I’d be investing in a show like this. Not a show like Mamma Mia. (Even though I’d realize a Mamma Mia is going to do much better commercially.) This show has much higher ambitions. And makes you think. It is trying–and sometimes succeeding–through both script and score, to tell us something meaningful about the human condition. It enriched me. Shows like Mama Mia are, for me, forgettable.

I hope the show can make it. It’s real musical theater, with a star, Kelli O’Hara, as strong as any singing actor we have in the theater today. And an important theater composer of today.

My fingers are crossed…..

* * *

Cast of Ragtime

Ragtime, with book by Terrence McNally, music by Stephen Flaherty, and lyrics by Lynn Ahrens, is one of the best musicals of the last 30 years. The production of Ragtime, directed by John Fanelli, that is now running (through May 4th) at the Westchester Broadway dinner theater, is one of the biggest and most satisfying productions I’ve seen there in years. There is an epic grandeur to this musical. And I like this production a lot. I’d go see it again, if I could.

Coalhouse & Sarah

The star–and he ought to be billed as such, because he is the heart and soul of this production and does an excellent job, although the theater for some reason is simply listing cast members alphabetically–is the single named actor known as Fatye, playing Coalhouse Walker Jr. I’ve enjoyed his work in such past productions at the theater as Big River and In the Heights, but I gained a new–and much greater–appreciation for him here. Fatye sings well, and acts the role with an endearing mix of vulnerability and strength. He makes the character very sympathetic. He gives a memorable performance. And there is a nice chemistry between him and his leading lady, Brittney Johnson. Most cast members in this production do a good job. Todd Ritch, whom I thought was miscast as the Artful Dodger when this theater presented Oliver a while back, is right on the money as Younger Brother in this production; he’s excellent. Nadine Zahr is a very likeable Emma Goldman. Jimmy Tate, who moves so well, gets a chance to make the most of his time onstage; it’s always a treat to see him, and I wish there were more for him to do. (There will be other shows.) The big ensemble numbers in this complex musical are staged well, and sung well. Ragtime boasts one of the greatest of opening musical numbers, and the large ensemble carries it off very well.

Baseball Baseball |

Mother & Tateh |

The only actor who really disappointed me, at the opening-night performance, was the young actor playing the role of the Little Boy, who recited lines too mechanically, and seemed awkward on stage. I wish more care had been taken in casting that small but vital role; the Little Boy is the very first character we hear from in this play–and in any production, first impressions count for a lot. The first actor we hear speaking in any show sets a tone. The original Broadway production of Ragtime featured an excellent young actor in the role–whom I remember the producer berating so harshly at the recording session for the cast album, I was alarmed; no young actor should ever be treated so badly; the boy soon quit the business and is today a bartender. (Incidentally, the role of the Little Girl in the original Broadway production was played by young Lea Michelle, who is well-known today for her work on television’s “Glee” and hopes to star in a proposed Broadway revival of Funny Girl.)

This production of Ragtime at Westchester Broadway is warmly recommended, and prices are reasonable–extremely so, considering what you get for the money. Go, if you can! (I didn’t much care for the previous show at Westchester Broadway–but this production is a winner.) Here’s a promotional trailer for the show:

* * *

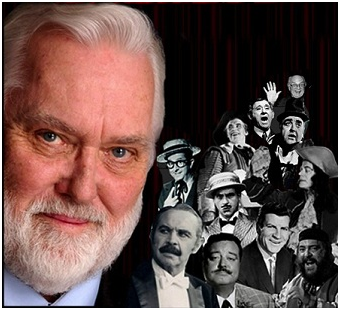

Jim Brochu

I’m glad I saw Jim Brochu’s one-man show, Character Man, at Urban Stages. It’s a very well crafted homage to an array of great Broadway characters: Zero Mostel, Jack Gilford, David Burns, Lou Jacobi, Barney Martin, and many more. I enjoyed the backstage stories and the songs very much. And Brochu’s self-deprecating wit is easy to take.

The show also made me feel sad in a way, because I’d admired all of the men he spoke about, I remembered vividly their work, and some of them I’d known personally. And the show made me feel a great sense of loss; it heightened my awareness that so many engaging performers, who’d given me so much pleasure via their work on stage, were all gone. The friend I took (who’s in his mid 20s) did not know the performers referenced in the show, but the show worked for him, no less than it did for me. And that speaks well for how effectively Brochu has put this show together.

Brochu conjured up the various “character men’s” personalities, and he sang songs associated with them, with affection and verve. Projections added to the show. While I don’t, at present, have a video clip from this particular production at Urban Stages, here’s a video sampler from an earlier production elsewhere, as Brochu was developing the piece, it gives a nice feel for his work:

Incidentally, producer Peter Napolitano has been adding to the fun at Urban Stage by bringing in special guests to join Brochu for talkbacks after the performance. The night I was there, Lee Roy Reams and Sondra Lee added saucy personal reminiscences of David Burns, for example, that made us see him even more vividly. I think some of what they shared would be well worth adding to the show.

* * *

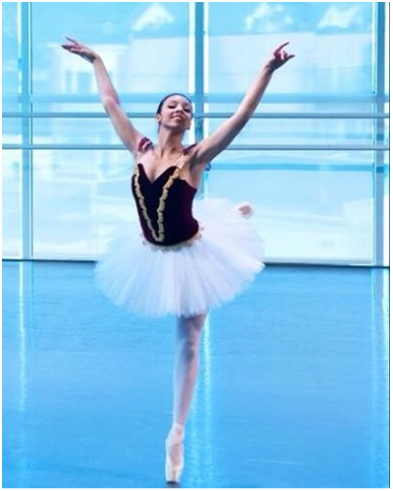

Ben Youngstone receiving gold medal in the CT Classic Ballet Competition

Congrats to dancer Ben Youngstone for taking home a well deserved gold medal at this year’s Connecticut Classic Ballet Competition. I am not surprised by this latest success of his. When I saw him playing small roles in a 2012 production of “The Nutcracker,” I singled him out for some praise, noting he was always interesting to watch on stage; there were some other dancers in that production who got much more exposure on stage who were not so interesting; they were technically proficient, but their dancing left me cold. That quality of being “interesting on stage” is hard to define, but any good director knows how vital it is, and how real it is. If I may digress for a moment, I’d like to give you an example.

One time I picked three dancers from a show I was directing–two gals and one guy–to be featured in front of everyone else in the cast for the finale. One dancer whom I’d passed over argued that he deserved to be showcased in the finale more than the ones I’d picked; he felt he was more seasoned and had better technique than they had. He tried to tell me things he could do as a dancer that they could not do. I told him it was simply a subjective judgment call on my part as the director, and I had to go with my gut. He was angry about not being spotlighted in the finale, about having to be just one of the background dancers. But in assessing talent, I’m not looking at individual moves a dancer makes; I’m looking at the overall effect a dancer produces. This fellow never even appeared happy when he danced; his expressions ranged from grim determination to bitterness. I’d already decided I could never use him again in a show; he danced with precision, but the vibe he gave off was unpleasant. I did not explain any of that to him. I simply told him I was making a subjective judgment call, which was true (if not quite the whole truth). Having technical skills is one thing. Creating art that touches people, however, requires more than just having good technique.

I love dancers who look like they love what they are doing. The best dancers are capable, at least sometimes, of projecting that quality. Brian LeTendre, whose dancing I’ve enjoyed a good deal in Broadway musicals and regional productions, radiated that same kind of joy even back in his student days at Juilliard, where he first impressed me; Tiler Peck, a great favorite of mine among ballerinas in the New York City Ballet today, had it even as a child, when I first took notice in print of her work; she projects a love of life, it is part of her artistry.

* * *

I got to delight in the dancing of Ben Youngstone, Katherine Lamagdeleine, Thel Moore, Nicholas Gray, Riley McGreggor, Alexandra Lopez, Julian Morgan, and others at the Nutmeg Ballet Company’s “Impact” Spring Show the other day… and I’m still beaming. I wasn’t there as a reviewer, just for fun, but I’d be remiss if I didn’t acknowledge a few high points. I’m not going through the whole show–which mixed classic ballet with contemporary work–piece by piece. I’m not analyzing everyone’s strengths and weaknesses. But I want to express my gratitude for the joy some standout dancers transmitted to me, and offer encouragement. There’s always some very good work to be found at the Nutmeg shows. And I’m grateful I was there.

Katherine Lamagdeleine – dancer to watch

Katherine Lamagdeleine participated on a couple of pieces as a guest artist. And oh! I relished seeing her again. With 18 dancers participating in the strikingly modern “Pulse 2” (choreography by Brian Reeder, music by Deadmau5), she drew my attention, and I can replay in my mind her work.. I loved the mix of spontaneity and sensuality she projected. A wonderful dancer. It was also fun seeing her, along with Cat Ward, Cydney Bronstein, Hope Friedman, Deanna Dewitt, Leticia Bitelli, Meagan Selinsky, in the imaginative MOMIX piece “Marigolds” (choreographed by Moses Pendleton).

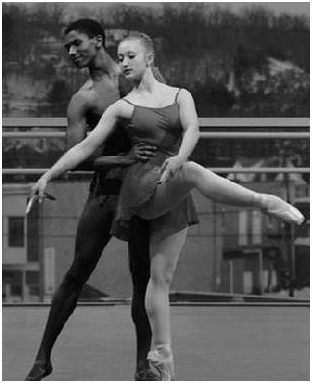

Thel Moore and Riley McGregor

Thel Moore and Riley McGregor made my heart soar as they danced the famed “Diana and Acteon” pas de deux. Moore’s mix of grace and strength is always attractive, and well suited for that number. McGregor, poised and restrained, was effective whether dancing on her own on in synch with him.

Now I must confess, there is something about that famous piece, choreographed many years ago by Agrippina Vaganova, that has always puzzled me. It is based on the classic Greek myth of Diana (also known as Artemis) and Acteon. And I loved Greek mythology in my youth. (Still do!) In the myth, Acteon was a hunter who chanced upon Diana, the Goddess of the Hunt, bathing naked in a pool in the forest. Startled, embarrassed and angered, Diana splashed water on Acteon, and turned him into a stag. (Never antagonize a goddess!) Acteon bounded away, unable to speak–and his fellow hunters, unaware of who he was, killed him. The myth has inspired assorted works of art (including a famous painting by Titian).

But I must admit, I don’t see how the dance correlates at all to that famed myth. If someone told me the dance was supposed to depict two gods falling in love (and Moore certainly seemed godlike, bounding about that stage the other day), I could see it. But how does the close partnering in that dance possibly suggest a chaste goddess, embarrassed at being seen nude by a mortal hunter, and then getting angry enough at him to turn him into a stag? They look more like a contented couple as they dance together.

With a stretch of the imagination, I could see those great, strong leaps of Moore’s as being “stag-like.” And McGregor’s carriage and bearing attractively suggested the pride of a Greek goddess….. But I honestly don’t see how this wonderful dance piece–which I’ve always loved, and which Moore and McGregor interpreted with flair–has anything to do with the story of Diana and Acteon. Madame Vaganova, of course, went to her reward many years ago… or I’d ask her what in the world she was thinking when she choreographed this piece. (If any of my readers wishes to comment on this subject–or anything in my column–I’m always glad to hear from you; you can write me at Footloose518@aol.com, anytime.)

I’m not seriously complaining, of course; I’ll take beauty for what it is, and Moore and McGregor were a joy to watch… Even if I never really saw an angered goddess taking her revenge on a doomed hunter up there on that stage….. Maybe Madame Vaganova read a different version of the myth than I did….

Ben Youngstone is always a delight, and I was happy to see him in the “Impact” show. I especially enjoyed his work in the dreamlike, contemporary “Untitled” (choreography by Victoria Mazzarelli, music: Maneesh de Moor). He feels the dancing, and it shows. He dances as if he’s making it up himself on the spot, and it is wonderful when a dancer is able to connect so thoroughly with the work, to inhabit it like that. I’m very grateful I saw him. When I watch him on stage, he seems larger than life.

I enjoyed the overall characterization projected by Deanna Dewitt as “Raymonda” (with choreography based on the original by Marius Petipa). I’m not assessing technical finesse, but the spirit conveyed, the capturing of the essence of the piece. The illusion of lightness appealingly projected.

And what a treat it was to see newcomer Nicholas Gray take on the challenge of the “Variation Gustave Ricaux” in Kirk Peterson’s “Lombardi Variations” (with music by Verdi). Here is a dancer to watch–a natural, clearly comfortable on stage, and radiant. The dancing will become more refined in years to come, I am sure; but already he has a terrific mix of precision, grace, and joie devivre. A pleasure to watch. And no one has to remind him to smile–his whole performance was incandescent.

Good male dancers are all-too-rare. When I hold auditions for shows, good singers are plentiful by comparison. So are good actors. (Hundreds graduate from schools like AMDA each year.) Good dancers–and especially dancers who can also act and sing well–are the most difficult to find. A major Broadway revival on On the Town–one of my all-time favorite musicals–is now being planned. And I pity the poor producers. Because every member of that show’s big cast–from the three sailors (who are the stars) on down–should be able to dance well. That was the way Jerome Robbins initially conceived the show, back in the 1940s. (That Broadway musical grew out of his ballet Fancy Free.) But it was easier then than it will be now, to find guys and gals who can dance that show the way Robbins intended. Leading men and leading ladies who are dance stars? Broadway just isn’t producing them anymore, the way Broadway once did. And that’s a pity. We could use a few more Gene Kelly’s and Gwen Verdon’s.

But it’s a funny thing about that quality of being interesting on stage. Gwen Verdon sure had it. I can look up from my desk here and see photos I took of her, on stage and off. And even just walking–even in the photos–she’s got personality. You’re drawn to her. Ann Reinking captured my attention back when she was a chorus girl, before she was famous; you couldn’t help notice she had something special.

I’ve gone back repeatedly to see Newsies–which for my money has the best dancing on Broadway right now. And it’s fascinating to see how cast changes affect the show, since different dancers have different strengths. When one left, his replacement simply had less “presence” and the character he played seemed to fade into the scenery; by contrast, when Giuseppe Bausilio took over another part in the show, the part seemed to gain in prominence; he simply commanded the attention. The Broadway production of Newsies is, generally speaking, very well-maintained, and it’s a terrific show, brilliantly executed. But finding dancers of that caliber is not easy. I will be curious to see how close the national tour (which will go out later this year) can come to the quality level of the Broadway show. Audience members may sometimes mistakenly assume that there’s a huge supply of top-level dancers. But there’s not.

There was excellent dancing in the Broadway production of Footloose, which I saw repeatedly. (The script for that show might not have been a masterpiece, but the dancing was terrific; my quote praising the dancing hung under the marquee of Footloose throughout its Broadway run.) But when the show’s top dancers, like the superb Mark Myars, were out, the quality of the production was noticeably diminished; they had swings who could cover all roles, if need be–but they weren’t on the level of Mark Myars; they couldn’t do turns-and-seconds with the precision or panache he had. And I sure didn’t envy the producers of the road-show company of Footloose, with a very young, green cast, and various members leaving and being added on the tour.

Finding enough good dancers for touring productions of Forty-Second Street–dancers who could come close to Broadway standards–was a challenge. Casting the last Broadway revival and national tour of West Side Story–finding dancers who could do the demanding Jerome Robbins choreography was tough. Some modifications to the choreography, to make it a little easier in spots, were quietly made. The producers of the Broadway production of Billy Elliot had to search internationally to find performers who could carry off the title role in that show; the number of young triple-threat performers who could play the role well is very small, and they had to go outside of the US to meet their needs.

So did I when I wrote and directed my Off-Broadway success George M. Cohan Tonight! In 2006. My star, Jon Peterson, was born and raised in England! H; he studied with the Royal Ballet; over time, he mastered tap as well as ballet, and he appeared in many musicals on the West End. He was brought to the US to star in the national tour of Cabaret, which he did brilliantly for a couple of years. I never imagined I’d wind up hiring a British performer to play the most quintessentially American of all song-and-dance men, George M. Cohan–but I held open-call auditions and no one else came close to matching Peterson as a charismatic triple-threat performer. Eight years later, he’s still doing the show for me, in city after city. And I’m grateful, because I still haven’t found anyone who can quite match what he does. Take a look at this video clip, which gives a sample of his work in my show, and you’ll see what I mean.

Over time I have found a few other performers who can play this role satisfactorily. (I found them through recommendations, not auditions.) And if we get bookings for the show that Jon Peterson cannot make, they take them instead and audiences are satisfied. They are talented, hard-working performers whom I respect and appreciate. But are they on his level? Not quite. The talent pool of triple-threat song-and-dance men is small. (In terms of dancing the role, the best performer I’ve seen after Peterson is Korea’s number-one musical comedy star, Im Chun-gil–one of three performers who’ve starred in my show in Seoul. Americans don’t know his name because he does not speak English. But he’s a thrilling dancer.)

Finding a suitably strong young triple-threat performer for one of the roles in a show I’m developing, Irving Berlin’s America, is very tough. The players who can do justice to the role are few. I had to search far afield to find someone to play this part for a tryout production in New Jersey this past year. I was very fortunate that Matt Nardozzi, who has solid Broadway and Hollywood credits, was able to fly up from Florida, where he lives, to do the gig. He’s excellent and totally reliable, and I’m lucky he happened to be free. He’s just been nominated for a Young Artist Award, for his work in my show–one of only four performers chosen nationwide. (For 35 years, the Young Artist Awards in Hollywood have honored outstanding younger actors of film, TV, and stage; he’s a past winner of the award, besides being a current nominee.) He’s up against some top competition (including a talented young actor from The Lion King on Broadway). I’m glad to see him honored with this nomination. He’s always working; he’s just finished a TV pilot, and has booked a nice role in a forthcoming film. But performers on his level–who can dance satisfyingly, in addition to singing and acting well, are hard to find. Ever time I go to see a musical or a dance program, I’m scouting available talent.

* * *

One of my neighbors, whose son wants to pursue a career as a dancer, worries his son is making an “impractical choice,” and should learn a trade instead. The father asked my opinion. I’d encourage anyone–especially someone so talented–to follow their heart, simply because it will make them happier. But the truth is, good male dancers are in short supply. It might not be an “impractical” career choice for the son at all, to try to make a career as a dancer. Some of my dancer friends, like Cody Green, are doing very well. Of course, it helps that Cody Green is so flexible–happy whether he’s doing pure dance for, say,. Twyla Tharp; doing contemporary dance backing a popular singer like Rihanna; or co-starring in a Broadway musical (he played one of the leads in the last revival of West Side Story. (Ben Youngstone, Thel Moore, Nicholas Gray… you’ll find work! Whether it’s in the world of pure dance, or in a Broadway show like Newsies or On the Town. They will need dancers as talented as you!) And of course, today’s good dancers may be tomorrow’s good choreographers. I’ve seen a number of fine dancers make that transition effectively.

* * *

When you enter my home, one of the first thing you see is a painting by Tommy Tune. Oh, he’s won nine Tony Awards for his work as a dancer/singer/actor, choreographer, and director. He also wrote a fine and inspiring autobiography (which I’ve often quoted from in lectures); he’s a sensitive photographer; and he’s an avid painter. I told him once that I admired that he had so many different talents; I like multi-talented people. He responded to the effect that it’s all one talent simply finding different ways of expressing itself. And he suggested it’s not so unusual to find a dancer or choreographer, say, who also likes to paint. And Chase Brock, the choreographer of Spider-Man and

more, also paints, among other gifts. So perhaps I shouldn’t have been surprised when I just heard that Samantha McCoy, who’s impressed me as a dancer and choreographer to watch, has just won a national award for a painting of hers–which I’m looking forward to checking out at Parsons in New York. Someday, maybe I’ll have some artwork of hers up on my wall, alongside of that neat artwork of Tommy Tune’s.

* * *

Jeff Whiting and Susan Stroman Jeff Whiting and Susan Stroman |

Choreographer Jeff Whiting |

And while we’re on the subject of multi-talented people who’ve started out as dancers…. Director/choreographer Jeff Whiting, who’s currently assistant director to Susan Stroman on the Broadway musical Bullets Over to Broadway (and has previously worked on such Broadway productions as Big Fish, The Scottsboro Boys, Hair, and Young Frankenstein) has created “Stage Write” software, which the Stage Directors and Choreographers Society (to which I belong) says sets “the new standard in documentation” for directors, choreographers, and stage managers who want to notate the blocking and choreography of their shows; lots of directors, choreographers, stage-managers, and performers will be in his debt for that. It’s already being used by various Broadway shows.

Whiting also heads the Open Jar Institute for Actor Training (http://www.openjarinstitute.com ) for high-school- and college-age musical-theater students; kids get to study in the summer with respected pro’s like John Kander, John Tartaglia, Joanna Gleason, etc. (I’ve known people who’ve taught there and have studied there; all speak highly of it.)

Why did he choose to name his actor-training program the “Open Jar Institute”? I like his explanation: “A group of researchers did a study on fleas and discovered the open jar phenomenon. They took a group of fleas, put them in a jar and closed the lid. The fleas, which have a high capacity to jump, kept hitting the lid of the jar as they jumped.

After a few days, the fleas learned the limitation of where the lid was and began jumping just below the height of the lid. A week later, they took off the lid of the jar. The fleas continued to jump at the adjusted height–and, although the jar was now open, they never jumped out of the jar. Like those fleas in the open jar, so do we, as humans (and artists) often adjust to the limitations others set for us to the point where we stop doing our very best – even when there are no limitations – and we never achieve what we were meant to achieve.” The Open Jar Institute, Whiting suggests, aims to help people realize their potential–which may well be greater than they realize. I like his thinking.

* * *

Music Man

I have very mixed feelings about the all-African-American concert version of Meredith Willson’s The Music Man that I caught at the New Jersey Performing Arts Center. This was a joint production by the New Jersey Performing Arts Center with the Two River Theater of Red Bank, New Jersey, and it was presented at both venues. There was a great deal to enjoy, and the evening certainly started out strong. I was glad I went. The presentation suggested possibilities, I hope further development will occur. I like the concept of an all-Black version of The Music Man. And the potential was clearly there.

But the show I witnessed appeared sadly under-rehearsed. There were several terrific performances–several players who created perfect characterizations–and I’ll get to them in a moment. If everyone was on that level, I’d say, “Move this Broadway now.” But a chain is only as strong as its weakest link. And it was frustrating that some of the singing actors did not seem secure in their vocal parts. Some of the harmonies were marred; the show’s well-known barbershop quartet numbers did not come close to being what they should have been. Sometimes some of the actors in this production seemed tentative–singing vocal lines, as if they simply had not mastered their vocal parts. I find it hard to excuse such lack of professionalism–especially in a classic musical like The Music Man. People need to do their homework. Every member of that cast should have listened to the original cast album until every melody and every harmony was thoroughly inside of them.

I liked the overall concept–the idea of an all-Black version of The Music Man–reflecting the reality that there were Black communities in the midwest in the period depicted. There were enough excellent moments to make me hope that, properly developed, this show could go to Broadway. There were some performers so deft and adroit in their characterizations, it was possible to see how could such a production could be.

In terms of characterizations created, the standouts in the cast were several supporting players: Trent Armand Kendall (superb as Olin Britt and one of the traveling salesmen–his was the first voice we heard in this production and he got the night off to a great start with his richly delivered words), Lawrence Clayton (a magnificently blustery Mayor Shinn), Bernard Dotson (just right as Charlie Cowell), Kevin Free (an engaging Marcellus Washburn), and NaTasha Yvette Williams (as delightful a Eulalie Mackecknie Shinn as I’ve ever seen). All of these players delivered wonderfully oversized performances; they lade the most of every line. Trent Armand Kendall in particular was a real treat–a lesson in old-time showmanship from start to finish. Kevin Boseman–an adult actor–did the best anyone could have done playing the role of the lonely child with the lisp, Winthrop Paroo–Boseman was sympathetic and endearing. But casting a real child to play that role always works better, and evokes more sympathy. These supporting players showed how well a wisely casy all-Black version of The Music Man could work. But the costars of this production–Isaiah Johnson as Professor Harold Hill and Stephanie Umoh as Marian Paroo–were not up to the challenges of those roles. Johnson was pleasant and likeable–he was not the larger-than-life spellbinder the role calls for. He’s got to have more presence than the others in the cast. (So, ideally, should the actress playing Marian Paroo.) He did not. Trent Armand Kendalll–one of the best character actors in theater today–outshone him.

The production was done with a small cast–just 11 players–and an edited, cut-down version of the script. I’d love to see a first-rate, full-scale all-Black version of The Music Man mounted on Broadway. But there should not be compromises in cast size or script. The libretto of The Music Man is as well constructed as any libretto in musical theater. I was painfully aware of every cut, and they did not improve the show. The show started very strong; the opening scene was very well played. But it lost energy towards the end. And the small cast size mean there was not much of a payoff at the end. We should have seen a boys’ band in uniform; instead we saw one adult (Kevin Boseman, playing Winthrop Paroo) in uniform, representing a boys band. The effect–the impact–is not the same. Adaptor/director Evans Haile has shown that there are great possibilities in an all-Black version of The Music Man. And some of the cast members he chosen delivered their lines with aplomb. The potential for a great production is there. I’m grateful I saw this–I adored the performances of Kendall, Clayton, Williams, Dotson; they lit up the stage when they spoke. If only everyone had delivered their lines with equal verve.

* * *

The Other Josh Cohen

The Other Josh Cohen, a cute little musical play, co-written by and co-starring David Rossmer and Steve Rosen, gave me plenty of laughs. Perhaps I should be grateful for that. But the production seemed too small for Paper Mill Playhouse and the production felt a little cheap. I’ve seen countless shows at Paper Mill since the 1970s; “cheap” is not a word I’ve ever before associated with Paper Mill. But the set seemed lost in that huge theater. The limitations of some members of the small cast seemed all too obvious. This is one of those plays were some musicians also double as actors, saying some lines. And some of those musician/actors weren’t very good at delivering lines, and did not have much presence. Ouch!

This show started out in a small theater in New York. But what seems charming and acceptable in a small theater isn’t always equally charming and acceptable in a big venue. Our expectations are lower if we see a show in a festival or in a small theater Off-Broadway (or Off-Off Broadway). If they are cutting costs by having musicians double as actors, we can accept it in good fun. But in a bigger theater, with higher ticket prices, expectations are somewhat higher.

The acting in this production was not always up to the standards I expect from Paper Mill. And an actor who has little presence stands out more–is even more exposed–in a big theater than in a little one.

Over the years, Paper Mill has occasionally done some impeccably cast small shows, with handsomely designed sets, that felt like first-rate theatrical experiences. And they have done many outstanding productions of big musicals. Paper Mill has directors who are masters at mounting big traditional Broadway musicals. (Their production of Gypsy, directed by Mark Waldrop and starring Betty Buckley,. had as much impact as any production I’ve seen anywhere.)

This production of The Other Josh Cohen disappointed me a bit. I thought the writing of the dialogue was very good and the two co-stars were likeable enough, But the production itself felt like it had been ripped from a small theater where it belonged, and had been plopped down into the wrong venue. It was being asked to do more than it was capable of.

The best performer in The Other Josh Cohen was Kate Weatherhead, playing to perfection a variety of roles. Funny. Shrewd. Professional. Likeable. And lots of that mysterious quality, presence. She had more presence than anyone else on the stage, and made the limitations of one or two others all the more glaring.

Don’t ask me to define presence. But it is real and it is vital. I’d buy a ticket to see anything Kate Weatherhead was in. Rossmer and Rosen can write terrifically funny dialogue. If Paper Mill had a second theater–a smaller venue for smaller shows like this one–and if the director had found a few more actors on Weatherhead’s level, this would have been a far more enthusiastic review. Because I laughed a lot. And much of the script is fresh and funny and surprising. But pinching pennies to hire some actor/musicians who are limited can lower the impact of the whole enterprise. And it looked to me like that’s what had happened.

* * *

But boy! Having presence on stage–that is a rare and wonderful quality. I go to a lot of readings, showcases, college productions. Most of what I see is forgettable, not worth writing about. I’ll make note of an occasional performer, because they simply have more presence on stage than the others. Of the many younger I’ve seen in college productions in recent years, Hofstra’s Anna Holmes is a standout, simply because she’s got so much stage presence. She walks on stage–clearly comfortable with herself, comfortable in her own skin, glad to be there–and takes ownership of the stage. She has a bright future. People will pay to see that.

* * *

|

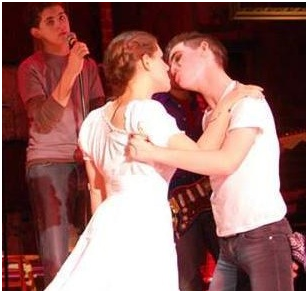

Joe Polsky, Martha Epstein Will Conard _ Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson

Will Conard, Martha Epstein, Joe Polsky – Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson

And speaking of presence, and of good productions… I’ve never seen a high-school production of a contemporary musical carried off with greater zest and zeal and professionalism (and with such well matched leading players, to boot) than the remarkable production of Alex Timbers and Michael Friedman’s Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson that

I caught recently at the Fieldston School, directed by Clare Mottola. I have been seeing productions there for years (Cabaret, Spring Awakening, Sons of the Prophet, Columbinus….); professional musicians I know and respect (like noted sax man Chuck Wilson, whom I profiled in my book Jazz Veterans), have told me the school does exceptional shows; and younger actors I’ve worked with have said the same thing. Year after year, Mottola manages to get performances out of youths I’d scarcely thought were possible. She is a very good director, and her interpretation of Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson–funny and sexy and daring and confrontational–soared from start to finish. She happened to have two excellent young actors to play Andrew Jackson and his wife; Will Conard’s rockstar swagger was irresistible and Martha Epstein’s depth, sensitivity, and vulnerability impressed. (We see them both in the photo; behind them is a backup singer with a beautiful voice, Joe Polsky.) Those are talented youths, with obvious great potential. But I loved the way Mottola imposed a strong sense of style–an exaggerated version of reality–on the cast. The whole production had a Brechtian intensity, and every actor in the ensemble–Rohit Gopal, Sophie Moss-Slavin, Truly Siskind-Weiss, Max Beer, Julia Rosenberg, Kate Rosenberg, Adam Kamo, et. al.–seemed to be on the same wavelength. That is rare. And it was wonderful to see. The production, overall, succeed more than a number of professional productions I’ve seen this year have. If my schedule permitted, I’d have gone back to see it again. But there are so many new shows, on and off-Broadway I’m eager to check out…. And we’ve begun rehearsals for a new production of my show One Night with Fanny Brice. And I’m teaching a new playwriting course. So time is limited.

* * *

One final note, for all of my friends who love theater… Tony Award-winning playwright Rupert Holmes (The Mystery of Edwin Drood, Curtains, Say Goodnight Gracie, etc.) will be interviewed by my old cohort from The New York Post, Michael Riedel, in a Master Class for the benefit of the New York Theatre Barn, Sunday, April 13th. You’ll have a chance to learn a lot from this gifted playwright–and benefit a good cause at the same time. The New York Theatre Barn helps nurture new plays. And they attract talented people. Space is limited and if you’d enjoy spending an afternoon with a respected, multi-talented playwright/songwriter, make a reservation now. It should be a memorable event. And Michael Riedel will add spice, too!

I hope I’m free that day. I’d love to hear what Rupert Holmes has to share about his life in the theater. If you might like to go, or want more info, click onto: Nytheatrebarn.org.

– CHIP DEFFAA, April 2nd, 2014

Leave a comment