ON THE TOWN… With CHIP DEFFAA

I’m back in the recording studio tomorrow, continuing with my ongoing project of recording rare–and in many cases, never-before-recorded–songs by Irving Berlin. I’m very proud of the series of albums we’re producing. I’ve carefully examined every song in the Berlin archive–some 1,200 songs!–searching for rarities deserving of greater recognition, and just the right singers to interpret them.

I’ve been reminded anew, of late, that impressive theater can be found in the most unexpected places. Some of the most intriguing theater I’ve experienced in recent weeks has been found in venues a bit off the main stem.

“Singing Beach,” a new drama by Obie Award-winning playwright Tina Howe, is having a world-premiere engagement, through August 12th, at the Here Arts Center, 165 Sixth Avenue, New York City. I caught the show July 29th, the night before its official opening. I was touched, moved, surprised. There is some very good work to be seen on the Here mainstage. And it is original work. Howe–a two-time finalist for the Pulitzer Prize–has something valuable to say. And, as always, she shows a remarkable gift for language, and for getting inside of a character.

This is not a perfect production, for reasons I’ll get to shortly. But if you can get a ticket for this limited try-out run (produced by Theater 167, and directed by Ari Laura Kreith), you will be rewarded. This is sensitive, impactful theater, and the best scenes will pull you in. The audience, the night I attended, was as quiet as any audience could be–hushed, still, attentive.

I hope the play will get further development, and further productions. There is some very good writing here, and some very good acting. There are some flaws, too. But the play deserves to reach a much wider audience.

The play takes place in Manchester, Massachusetts. Three generations are living in a beachfront home: a boy and a girl; their mother and step-father; and their grandfather, who’s largely incapacitated due to age and illness. He has suffered two strokes and is mourning the loss of his wife. He does not speak–perhaps due to the strokes, perhaps due to overwhelming grief. He is incontinent. The family, stressed for a variety of reasons, faces some tough choices; the grandfather may well be headed for a nursing home. Meanwhile, a hurricane is approaching, and all area residents are being asked to evacuate.

The first characters we meet are the boy, “Tyler” (played by Jackson Demott Hill, who appears to be around 14), and his younger sister, “Piper” (played by Elodie Lucinda Morss, who appears to be around 10). Hill is a remarkable young actor–vivid on stage, and with tremendous presence. I’ve praised him before in these pages; he was a standout–about as effective as any child actor I’ve seen on Broadway–playing “Peter” in the musical “Finding Neverland.” And he inhabits the character of “Tyler” comfortably, playing the annoying, irritating, pestering older brother so believably, that you–as a grown-up–almost want to go up on the stage and slap him. He tortures his poor younger sister in a way that rings all-too-true-to-life. (And reminded me a bit of how I treated my own poor younger sister when I was very young.) Hill is perhaps a bit older, taller than the character he is supposed to be playing. But excellent young actors are exceedingly hard to find. And he is a great asset to this production.

Singing Beach cast

Howe’s wonderful gift for dialog–a tremendous strength of hers, as a writer–is particularly evident in all of the scenes involving the brother and sister.

Playwright Tina Howe

Elodie Lucinda Morss, playing the younger sister, is, alas, uneven on stage. She doesn’t have the presence of Hill, or of the others in the cast–which is rather strong. To her credit, she is likable and unaffected. She is very good with physical business. When she hugs her grandfather, for example, it is utterly natural and honest; you feel her love for him–and that is great. But she did not always appear secure in her lines. (And the show began playing previews, July 22nd , a week before I caught it; there’s no acceptable excuse for not having the lines down 100% by the night before the play officially opens.) Several times she stumbled over her lines, as if she was trying to remember them. And each time she did that, she pulled me out of the moment; I was no longer seeing a character I believed in; I was seeing a not-fully-prepared young actress struggling to remember lines.

But more than that–like many young performers–she had trouble fully sustaining her characterization. She was very good in some scenes (particularly early in the play)–but not quite where she should be yet, in some other scenes. As if, perhaps, she needed a bit more time to rehearse. I don’t wish to be too harsh. Ten-year-old performers, generally speaking, have not had much training or experience, and a great deal is being asked of the young actress playing this big part.

Overall, in many ways, Morss was pretty good. In much of the play, I liked her work. And I understood every word that she–and every other person in this production–uttered. Which is good. (Young actors often have problems articulating clearly.) But this is too important a play to settle for merely “good” work. If the play has a future life–and I certainly hope it will–the producers will need to find a child actress who is “great,” not merely “good.” It is not easy to find such a person. But Morss, although likable on stage, is the weak link in the present cast. In some plays having one weaker child actress might not matter too much–but this play is unusual in that the role of the little girl is actually the most important role in the whole play. So it’s essential to cast that role right.

Howe–and I give her great credit for this–has written an unusually meaningful role for a 10-year-old actress. (Such roles are extremely rare in the theater.) Much of this play is actually presented from the point of view of the young girl; and Howe does a fascinating job of getting inside the young character’s head.

We see the child’s fantasies–dreaming of a world in which her brother is kind to her, and her real father–not her stepfather–is still with her. Her favorite TV hero, quite plausibly, is part of her dreams, too, as is a beloved, idealized school teacher. In her dreams, her grandfather can speak to her. And the love of the little girl for her grandfather–she will do anything to spare him the indignity of ending his life in a nursing home–is the one emotion that propels this play.

Howe has written an extraordinary role for a young actress. This production does not, at present, have the ideal actress to play that role. Morss is pretty good–but this play is too important to settle for an actress who’s not fully up to all of the challenges.

The rest of the cast is solid. It is always a great pleasure to see on stage John P. Keller–whom many will recognize, and remember fondly, from his sympathetic work on the HBO series “Boardwalk Empire.” He’s first-rate here, playing both the step-father and the father. (I would have welcomed more scenes showing the relationship of the father and mother; I wanted to know them a bit better.) And I’m always glad to see Tuck Milligan. This Broadway veteran (who won the Helen Hayes Award for his work in the Pulitzer Prize-winning play “The Kentucky Cycle”) has the thankless task of playing the largely bedridden, mute, pained grandfather. And Erin Beinard–new to me–is appealing in the dual role of the mother who is agonizing over her father’s fate, and the schoolteacher cheerfully advising her students of the dangers of climate change and of the enduring wisdom of the Beduins.

A. Singing Beach company

I loved the set by Jen Price Fick and the lighting design by Matthew J. Fick. The way the little girl’s toy wooden boat began to glow, leading us into a fantasy sequence, was an inspired touch. Perfect!

I don’t think the ending of the play is quite where it needs to be yet. I’m confident that–with a bit of tweaking–the final scene could be made to pay off more strongly. There is so much that is effective and moving in the play, I want the final scene to hit home a bit harder. But I trust that this play will have more of a life. And the playwright and director may, in time, find a way to make the final scene’s point as powerfully as possible. The final scene is not quite there yet. It’s got to land better, and bring the audience to strong applause. But this play has a future; there is much here that is just right; and the ending, I trust, will be perfected in time.

The best moments in this play certainly ring true. And they hit me particularly hard, I might add; one of my parents was largely incapacitated by a stroke; and this play feels sure feels true in that regard. Howe–who gave us the memorable “Coastal Disturbances”–is an important writer. I’m glad I was present at Here to witness the birth of this play. I would very much like to see it again.

* * *

I’m very glad I got to catch the New York premiere of “Terazin”–a drama written and directed by Nicholas Tolkien (whose great-grandfather, J. R. R. Tolkien, gave us “the Hobbit” and “Lord of the Rings”)–at the Peter J. Tharp Theater on 42nd Street. It’s about the persecution of Jews by the Nazis, and life in the concentration camps.

The good news is: Tolkien can certainly write. The best scenes have life and color, and power. The energy, in the best scenes, is fantastic. However–despite the effectiveness of some scenes–the play, as a whole, did not really work for me. And I wish that Tolkien had let a first-rate director supervise the production instead of directing it himself; I have a hunch that Tolkien may be too close to his work to see some structural problems that might be obvious to most any seasoned, objective, theatrical observer.

The good news is: Tolkien can certainly write. The best scenes have life and color, and power. The energy, in the best scenes, is fantastic. However–despite the effectiveness of some scenes–the play, as a whole, did not really work for me. And I wish that Tolkien had let a first-rate director supervise the production instead of directing it himself; I have a hunch that Tolkien may be too close to his work to see some structural problems that might be obvious to most any seasoned, objective, theatrical observer.

I want to encourage Tolkien because he’s clearly capable of writing with great flair, and honesty, and verve. That’s rare. And it’s wonderful. And there were many moments in the play were just terrific. I’m interested in seeing more by this writer, because he created some individual scenes that caught fire. And writers who can write with such feeling and passion are rare. But he does not appear to understand yet the importance of pacing and restraint, and of structuring a drama so it builds.

Playwright director Nicholas Tolkien

The first scene had considerable impact. We see the Nazis kill a Jewish man and his wife who are screaming in terror, begging for their lives. It’s cruel, and it’s awful. And it feels very real, happening on stage right in front of us. But dramatically, the problem is: Where do you then go from there?

The playwright gives us a number of subsequent scenes in which we see Nazis cruelly mistreating or killing Jewish victims who are screaming in terror. And after a while, the scenes have a diminishing impact.

There is a fine line between drama and melodrama. Tolkien, unintentionally, sometimes crosses that line. Someone needs to be telling the actors, when they are screaming all-out, to hold a little in reserve; the scene will actually have more impact. And someone needs to be telling Tolkien that, if you want the audience to fully feel the horror of scenes showing cruelty, you have to mix in more scenes of enormous contrast; that you must take time to build up to build up to scenes of terror, otherwise the senses become numbed or dulled, or overloaded. If there’s too much yelling and screaming and cruelty, it begins to lose meaning.

Tolkien’s heart is clearly in the right place, but he has to take his time to build tension or the release won’t count for much. I like the story he is trying to tell, but it will actually work better–the audience will, ultimately, feel more– if he can present the scenes of great cruelty more sparingly, with some softer, gentler scenes interspersed for contrast.

If I can add one more point. There was one staging choice that really bothered me. A couple of times, Tolkien had the actors–who were playing characters who’d just been killed–slowly exit the stage, sliding themselves offstage as unobtrusively as possible. But it appeared silly and distracting, having “corpses” sowly moving themselves offstage. The actors playing dead characters could have left the stage during a blackout, or could have been dragged offstage by others with the lights up; but having the actors move after they’ve supposedly just been killed did not work for me. In fact, when the actors playing dead characters began to move, I was simply confused; at first, I wondered if the characters had only been injured not killed by the Nazis.

Terezin

The cast was fine. One actor, Blake Lewis (playing an SS platoon leader), was exceptional, giving a performance that was adroitly shaded, varied, and nuanced. Really fine work by an actor I’d not seen before, showing great promise. I want to remember his name (along, of course, with Nicholas Tolkien’s).

* * *

I experienced a good bit of joy–and also some bittersweet moments–watching the National Yiddish Theater Folksbiene production of “Amerika: The Golden Land.”

(by Moishe Rosenfeld and Zalmen Mlotek, directed by Bryna Wasserman) at the Museum of Jewish Heritage, 36 Battery Place, New York City. There is much to appreciate here.

The songs, the singers, the musicians often put put a smile on my face. The performance gave me as much pleasure as any musical production I’ve seen lately. And you certainly don’t have to speak Yiddish to enjoy the show, which is performed largely in Yiddish, with English and Russian supertitles.

Yiddish songs certainly influenced American popular culture–the music produced by Tin Pan Alley, Broadway, Hollywood. This show is rich with melody. Occasionally, even if you’re not familiar with Yiddish theater, you might recognize some of the melodies, either because the songs became part of our popular culture “as is” (“Roumania, Roumania”), or were outfitted with new lyrics in English and recorded as pop songs. For example, the Yiddish song “Belz,” written by Jacob Jacobs and Alexander Olshanetsky, was transformed–with new English lyrics by Sammy Gallop–into Al Jolson’s song, “That Wonderful Girl of Mine.”

The show provides a nice overview of Yiddish songs and theater (and even some humor–the weather report is written and executed to perfection), and the storyline, about the immigrant experience, is one almost any American ought to be able to relate to. There is much to enjoy here.

Amerike–The Golden Land- ensemble

The National Yiddish Theater Folksbiene–founded in 1915–is the oldest theater company in America. And, sadly, it is one of only five professional Yiddish theater companies that are left in the whole world–there’s one other Yiddish theater company in NYC (the New Yiddish Rep); the others are in Warsaw, Bucharest, and Tel Aviv. The Nazis, in the Holocaust, killed most of Europe’s Yiddish-speaking population. The National Yiddish Theater Folksbiene strives to keep alive Yiddish culture. It has found a home now in the Museum of Jewish Heritage. And

I’m glad it has found a home. But I’m also somewhat saddened that Yiddish culture–which has given the world so much, in terms of literature, songs, theater, comedy–today seems to have something of a “museum piece” status. New York once was able to support not only a vibrant Yiddish theater scene, but a vibrant Yiddish press, and a vibrant Yiddish radio station. Much of the audience that once supported the Yiddish theater, press, and radio, is gone now.

Even the pool of performers raised by Yiddish-speaking parents has largely dried up. Nowadays, the National Yiddish Theater Folksbiene must, of necessity, cast some performers who do not speak Yiddish, but have learned how to sing, phonetically, the songs they must sing. The cast of this production (Glenn Seven Allen, Alexandra Frohlinger, Jessica Rose Futran, Daniel Kahn, Dani Marcus, Stephanie Lynne Mason, David Perlman, Christopher Teff, Maya Jacobson, Alexander Kosmowksi, Isabel Nesti, Raquel Nobile, Grant Richards, Bobby Underwood) gets a good, clean, consistently in-tune, appealingly musical ensemble sound. But it is a somewhat generic ensemble sound, much like the sound one would hear from any choral group at any good conservatory. It is the ensemble sound of typical contemporary theater professionals, without any specific ethnic character. If I went to a Folksbiene show 30 years, there were still older performers whose very beings–not just how they sang, but how they spoke, moved, shrugged, inflected phrases–reflected Yiddish culture. We’ve lost much of that. And I found myself missing some of that, at times, while watching this production. I missed accents, and inflections, and attitudes, and sounds.

Oh, there is much to savor in this show. I defy anyone not to respond to the joyous energy of Lowenworth and Rumshinsky’s life-affirming musical number from the 1920s, “Watch Your Step.” It is sung by the ensemble with gusto during the show, and then reprised with elan by the band at the very end. And it is magical. It is worth going to the show, just to hear that one number.

But I mourned a little, too, for older performers, now deceased (like Bruce Adler) whom I used to enjoy in shows like this, who brought an essential essence that is often missing now. And I wish some older guest artists who grew up in the tradition (like Joel Grey or Mike Burstyn) could have been included, so better represent the art for.

I found myself thinking of a family friend whose late mother used to make, from scratch, the greatest chicken soup in the world. Her daughter, who knows how much I loved her mother’s soup, recently had me to dinner, saying she would make for me–just the way her mother made it–the chicken soup that I loved. But it was a bit bland. I asked her if she’d followed her mother’s recipe exactly. She told me she had modernized the recipe “just a bit,” to remove as much fat as possible, since nowadays we know we must be aware of cholesterol. She said she removed the skin from all of the chicken, and she refrigerated the soup, so she could removed fat from the surface, before re-heating the soup. Otherwise, she said, it was her mother’s soup “almost exactly.” But whatever she had done, in modernizing her mother’s recipe, had come at a cost; because the character of the soup had changed. And I would have welcomed a bit of fat, to have the authentic old-time flavor.

So yes, I did enjoy this latest production of the National Yiddish Theater–but not as much as I enjoyed some of their productions, decades ago. A bit of the flavor was missing.

* * *

If you’re looking for a reasonably priced show your whole family will enjoy, take them to see the musical comedy “Annie” at the Westchester Broadway dinner theater. For much less than the price of Broadway tickets, they’ll get dinner and a show. If you drive, you’ll also appreciate that the theater provides free parking.

And there’s much to enjoy about “Annie,” which has settled down for an extended run at the theater. It’s a well-constructed show, with a winning score by Charles Strouse and Martin Charnin, and a book by Thomas Meehan that deftly mixes comedy, suspense, and pathos. It’s an almost surefire show. So long as you find the right girl to play “Annie,” enthusiastic other girls to play her six fellow orphans, and a likable pooch to play “Sandy,” you almost can’t miss–even if you fill out the rest of the cast with journeyman players. Kids love the show, and it charms adult, as well.

Fortunately, Westchester Broadway has found an excellent young actress to play “Annie”–Peyton Ella (who played “Gretl” in NBC-TV’s live telecast of “The Sound of Music”). She’s got just the mix of moxie, optimism, and showbiz savvy needed to put the character over. And she gives her all, singing “Tomorrow.”

Peyton Ella

Bill Berloni and Sunny

The dog playing “Sandy” (whose name in real life is Sunny) is trained by the same expert, Bill Berloni, who trained “Sandy” in the original Broadway production, and he’s just fine. (I had the pleasure of meeting and interviewing both Bill Berloni and “Sandy” at their home in Glen Rock, New Jersey, when “Annie” first opened on Broadway. Berloni has successfully rescued and trained many dogs over the years, and is today the go-to man in the field, if a dog is ever needed for a production.)

Bill Berloni and SunnyThe orphans are all suitably plucky, and are irresistible singing–as an ensemble–such numbers as “It’s the Hard-Knock Life” and “You’re Never Fully Dressed Without a Smile.” One of the orphans, alas, doesn’t speak clearly enough. She was the only cast member whose words I simply could not understand. She just swallowed her words. And I wish the director or stage-manager or someone would work with her.

I’ve enjoyed “Annie” since it opened on Broadway. And I’m happy that this production restores the song, “We’d Like to Thank You, Herbert Hoover,” which was cut from at least one of the Broadway revivals to shorten the show because–I recall the producers saying at the time–they felt kids’ attention spans had shortened since the show first opened on Broadway in 1977. The song, with residents of a “Hooverville” expressing their frustrations during the Great Depression, put the events in historical context. And the show has never felt overly long.

This production, however, misses some of the laughs in the script. It’s a pity, and I don’t think director/choreographer Mary Jane Houdina has always captured just the right tone. Some of the scenes, particularly early in the show, are being played too seriously, as if it were a drama or a tragedy, not a musical comedy. And, the night I attended, the audience wasn’t laughing much, early in the show.

When we first met Miss Hannigan, who runs the orphanage, she simply seemed like a mean woman who maybe drinks to much. But the role has to be played with a slight wink of the eye, so that she’s not exactly mean but, rather, “musical-comedy-mean”; so that she’s not an alcoholic, but a “musical-comedy-drunk”; so that kids don’t exactly find her scary, but sort of “funny/scary.” If the tone is just right–and Dorothy Loudon in the original Broadway production and Nell Carter in the first Broadway revival both had great fun with the role–it gives everyone in the audience permission to relax and have fun, and laugh. The show, on the night I attended, was being played–especially early in the night–just a tad too seriously. And people weren’t laughing.

Hopefully, Susan Fletcher, who plays Miss Hannigan, and Michael DeVries, who plays Daddy Warbucks, will find more of the laughs as the run progresses and they relax into the roles. They’re talented; but they seemed sort of reined-in, at times, as if afraid to go for the humor.

I was more satisfied with the performances of John-Charles Kelly (as FDR), Carl Hulden (“Bert Healy”), Adam Roberts (“Rooster”), and Aubrey Sinn (“Lily”), who seemed to be having more fun on stage. And Roger Preston Smith–who adds something to any show his in–was perfection as the butler, “Drake,” a reminder that a good actor can make a lot out of even a small role. And he found a laugh, drawing out the word “Mudge” just so, that wasn’t even in the script!

It saddens me that no mention is made anywhere in the program of Charles Gray, the brilliant cartoonist who created and–for more than four decades–wrote and drew the comic strip “Little Orphan Annie” that inspired this musical. He created the characters of “Annie,” “Sandy, and “Daddy Warbucks.” He deserves some form of credit or recognition. I’ve never seen him acknowledged in the program of any production of “Annie.” And that’s a pity. Without him, there would never have been this musical comedy. And he was a great story-teller. After his death, a succession of other cartoonists and writers tried to keep the strip vital, but without him it gradually went downhill, losing readers under the Chicago Tribune Syndicate, which owned the rights, eventually pulled the plug.

* * *

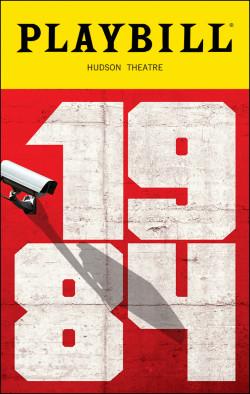

Speaking of giving credit where credit is due, I’m disappointed that no space could have been found in the Playbill for “1984″ to provide a bio for the late George Orwell, whose masterly book of the same name provided the inspiration for this play. That’s really shameful!

Somehow they found room in the Playbill to devote three whole pages to bios for the producers of this Broadway production. And room, of course, for bios of all of the actors, directors, and so on. But couldn’t someone have remembered George Orwell, that great champion of the individual over the group (whether the group was a corporation, a political party, the State–or a group of producers). He would have found it quite ironic, I’m sure, that there are bios for all of the money-men who funded this production, but none for the original writer of “1984.”

I’ve always loved the book “1984.” And terms and concepts that Orwell invented have become something like public property–understood worldwide.

1984-Big Brother is Watching You

I wanted to love the play, and I stepped into the Hudson Theater with high hopes. I found the play intriguing, but often confusing–at least early in the show. For my tastes, it took too long to gather all of its powers. I was sort of fidgety in much of the first act, waiting for it to all come together. But the last 30 minutes were absolutely riveting–first-rate stagecraft. Was it worth it? Yes! And I’d like to see the production again. I think I’ll appreciate it more, and understand it better, the second time around.

I also want to re-read the original book. I’m a great admirer of Orwell. He deserves an international holiday in his honor. He was a great crusader for the individual over the state. That book was his ultimate statement, his manifesto. And it took courage to write as he did. (One publisher turned Orwell down because he thought Orwell’s manuscript was a veiled criticism of the Soviet Union, and he felt that all with leftist sympathies should be sympathetic to the Soviet Union. Of course Orwell was against the Soviet Union, but he was against “groupthink” mentality wherever it might crop up.)

I must add, I’m very happy to see that the Hudson Theater has been restored to use as a Broadway house. I was calling for this to happen, many years ago. Built in 1903, it’s a grand theater, rich in history, and it is terrific to have it back. The lobby, incidentally, looks spectacular–rich with detail, and gold-leaf, and domes of Tiffany glass in the ceiling. The lobby has great character and elegance. And I love the box-office windows, flanked by busts of Hermes. Just terrific. I’m happy to hear that the backstage area, and all equipment needed for lights, sound, and scenic effects have been brought up to date. The auditorium itself, however, looks a little plain–like they haven’t completely renovated/restored it to how it originally appeared. Oh, the walls are freshly painted. But the lobby is so magnificently detailed and ornamented, I find it hard to believe the auditorium itself was always this plain. I wish the theater’s current owners could examine carefully all available photos of the theater in its heyday, in the first two decades of the 20th century. And see if there might have been elements–whether gold-leaf detailing, or wood paneling, or tapestries or drapes, or other ornamental details–that were once part of the design but have been lost over the years. And try to fully restore/renovate the house. The theater looks good, but the renovation/restoration has a somewhat unfinished feel to me. The lobby is so magnificent, the house itself ought to have a more consistent feel.

I like the old posters in the stairwells, of shows that played this theater in bygone years; they remind us of its great history. George M. Cohan–known in his day as “The Man Who Owned Broadway”–loved the Hudson Theater and considered it a lucky house. He appeared in a couple of significant productions there. (I have vintage Playbills.) And he produced 10 shows at that theater. He ought to be represented somewhere in the theater; he was an important part of its history.

* * *

I’ve seen “How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying” many times, many places. I didn’t see the original Broadway production, alas–although I loved the cast album–but I’ve enjoyed the Broadway revivals, and other productions. Just this year, for example, I got a kick out of seeing the kids at New York’s Professional Performing Arts School do a production.

I just enjoyed seeing the Leonia (New Jersey) SummerStage production of “How to Succeed,” directed and choreographed by Ray Yuccis–a mainstay of New Jersey theater. And it felt almost like seeing a new show.

Yuccis presened the show uncut. Nowadays, most presentations of the show cut a number or two, or three (the numbers most often cut are “Cinderella Darling,” “Coffee Break,” and “Paris Original”–they are cute numbers but not essential to the plot). And they cut lines and scenes, to shorten the running time by 20 or 30 minutes, or more.

Audiences nowadays are used to shorter productions than audiences were used to in the early 1960s, when “How to Succeed…” was first running. So even though I’ve seen “How to Succeed” a number of times, this was the first time I saw the whole show, as originally offered back in the 1960s. This was the first time I ever saw the musical number “Cinderella Darling.” And this was the first time I got to hear some funny lines involving Bud Frump, the boss’s nephew. I can understand the desire to streamline the show; it moves quicker with the cuts. But I was very glad that director Ray Yuccis gave me a chance to experience the full script and score. And the longer script helped us to better understand Rosemary’s position; she emerges as more fully human, and sympathetic. So I’m grateful I got to see this production.

How to Succeed

Naturally, I don’t judge local summer-theater productions by the same standards as Broadway productions. This is community theater, and the director/choreographer has to pull together players of considerably varied abilities and experience, and create an entertaining production on a very limited budget. Yuccis got good performances out of his cast, and made the ensemble numbers charming.

And he found credible actors for every one of the major roles, which isn’t usually the case with summer theater productions. Damon Quattrochhi (as “J. Pierpont Finch”), Steve Moldt (“J. B. Biggley”), and Jazmin Palmer (“Rosemary”) all did justice to their roles. And there were a few very pleasant surprises among the supporting players.

Brian Joseph Hajjar, a graduate of NYU Steinhardt, was a real find,; he carried off the role of “Bud Frump” with a mix of glee and pathos–this is the first time I ever felt sorry for “Bud Frump”–that was delightful. Messalina Morley was a terrific “Hedy”–sexy and funny. And “Joanne Moldt”–warm and human and ethnic as “Smitty”–was as effective as anyone on stage. Very professional work. She could be an asset to any stage production or sitcom. She made “Smitty”–which is often a “nothing” character–feel like a key character. It was such a wonderful discovery for me to see her in this production. I look forward to seeing more of all of those players–new to me!

Local theater shows don’t have, by any means, Broadway-style production values. And the singing/acting/dancing may be unpredictable. But it’s always fun to check out local productions. You may see a star-to-be, at the start of his or her career. (Long before Rob McClure was starring in shows on Broadway, for example, I was seeing him getting his start in shows in New Jersey.) You may see also see some middle-aged folk who perhaps could have made it as professionals in theater but opted instead for more conventional jobs that promised greater financial security. And you get to see, for very little money, some great shows–like “How to Succeed”–that never grow old.

* * *

I’m back in the recording studio tomorrow, continuing with my ongoing project of recording rare–and in many cases, never-before-recorded–songs by Irving Berlin. I’m very proud of the series of albums we’re producing. I’ve carefully examined every song in the Berlin archive–some 1,200 songs!–searching for rarities deserving of greater recognition, and just the right singers to interpret them. Getting to record these songs with some of my favorite artists is a source of boundless joy for me. And for me, part of the fun of seeing so many new shows is discovering new artists to record. I love every bit of the process, whether I’m working with seasoned veterans or up-and-coming artists who are recording for the first time. My Dad impressed upon me, as I was growing up: “Do what you love; the money will find you.” Good advice.

— CHIP DEFFAA, August 4, 2017

Leave a comment