ON THE TOWN… with Chip Deffaa, January 6, 2019

This production’s cast isn’t quite as perfect as the one I saw years ago. Fierstein is a unique performer; he owned the role of “Arnold Beckhoff,” which he originated. And I haven’t seen anyone over the years who can match his performance in that role. (And friends of mine have tried. Cas Marino starred in the last little revival in New York.) But I succumbed to the charms of this exceptional play once again–even if I did miss seeing Fierstein himself on the stage. He’d be too old to play the role now, nearly 40 years after he first played it. But he wrote the piece for himself, and it fit him perfectly.

[avatar user=”Chip Deffaa” size=”96″ align=”left” ] Chip Deffaa, Editor-at-Large[/avatar]As I look back on the year that’s just ended, I want to comment on a couple of significant productions I caught that, for one reason or another, I haven’t mentioned previously.

I think “The Girl from the North Country”–which ran in a limited engagement from September through December at The Public Theater–just might have been my favorite musical of 2018. It’s very powerful theater. It was written and directed by Conor McPherson (author of “Shining City” and “The Seafarer,” among other plays that I’ve praised previously in these pages)–who just might be my favorite living playwright– with a score consisting of songs by Bob Dylan.

The Girl from the North Country – Playbill

It’s a dark piece–honest and effective. And it gradually pulled me into it, until I felt I was right there in their world. I hope I have a chance to see “The Girl from the North Country” again. I hope it transfers to Broadway with the current cast intact. (They had the strongest ensemble cast I saw in any show in New York this past year.) And–I rarely ever say this about a production–I would not change a thing.

This production needs to go into one of the more intimate Broadway houses–perhaps something like the Lyceum or the Golden or the Helen Hayes Theatre, if they were available; it would be lost in a huge Broadway house. There are no huge production numbers in this show. And producers will want to preserve the closeness of audience members and characters on stage. I found “The Girl from the North Country” compelling theater–and quite unlike any musical in town. It’s closer in tone to Eugene O’Neill’s tragic “The Iceman Cometh” than to a typical musical. More like a tragic drama with songs. But I liked it a lot. The Public Theater has given us a near-perfect production.

McPherson has an unhurried way of telling a story that I like. His plays often take their time in gathering their powers. He introduces us to one character after another, gradually giving out bits and pieces of their histories, letting us fill in the gaps from our imagination. The characters–even if only partially sketched–feel curiously real. We feel their needs, their hopes, their dreams, their desperation.

The Girl from the North Country

The action takes place in a rundown boarding house, in cold, unforgiving Duluth, Minnesota, in the depths of the Great Depression. The innkeeper–the man at the center of so many gradually unfolding stories–is played with characteristic honesty and intensity by Stephen Bogardus. I’ve been enjoying his work on stage for 45 years. This is one of the best plays I’ve ever seen him in. Oddly, he does not get to sing in this play at all. (A pity, because he is a first-rate singing actor, as he proven in countless musicals over the years: “On a Clear Day…,” “Bright Star,” “White Christmas,” “Falsettos,” “High Society,” “Man of La Mancha,” and so on. But he is also an excellent dramatic actor, as he’s demonstrated in straight plays like “Love! Valiour! Compassion!” and “Go Back to Where You Are,” and I can accept the logic of having this one central character not sing.) The songs in this show tend to serve as oblique commentaries on the action–the singing-actors at oldtime microphones serving as a kind of Greek chorus. Bob Dylan’s genius as a songwriter is displayed well.

[

The Girl from the North Country

And special thanks must be given to Simon Hale, the show’s orchestrator, arranger, and musical supervisor (with addition arranging contributions by Conor McPherson); Hale deserves an award for his work. Although the various songs were written over a span of about five decades (from 1963-2012), the arrangements make them feel almost like folk music from the 1930s; they seem to fit–to a greater degree than I could ever have imagined possible–the period depicted in this play. And even songs that might be highly familiar (like “Forever Young” and “Like a Rolling Stone”) sound new, fresh, different; they feel like they belong in this world.

There is a good deal of despair in this musical (along with some significant moments of optimism, hope, and pride). It is not a smiley, cheery, “feel good” kind of show. But I was touched by the characters’ stories and secrets. I wanted to know these characters better. And I was very glad to have spent two-and-a-half hours in their company.

Now I want to list every member of the cast, because all members–whether familiar to me from memorable past stage success (like Marc Kusdisch and Luba Mason) or brand new to me (like Sydney Jame Harcourt and Kimber Sprawl)–contributed meaningfully to this potent work: Todd Almond, Jeanette Bayardelle, Stephen Bogardus, Sydney James Harcourt, Matthew Frederick Harris, Caitlin Houlahan, Robert Joy, Marc Kudisch, Luba Mason, Tom Nelis, David Pittu, Colton Ryan, John Schiappa, Rachel Stern, Kimber Sprwal, Chelsea Lea Williams, Mare Winningham.

I hope I get a chance to see this again. This is an important piece. It’s serious theater, artfully mounted. And a further reminder–if any were needed–of the value of New York’s Public Theater. (Oskar Eustis, artistic director of the Public Theater, is upholding well the legacy of the late Joe Papp, who founded the Public Theater.) Commercial Broadway producers, for the most part, would not be in a hurry to take a gamble on such a dour and brooding musical. But New York’s not-for-profit Public Theater , Off-Broadway, has done a first-rate job. Audiences responded. This limited-engagement run sold out quickly.

I am confident this production will have a future on Broadway and then in regional theaters and college theaters. I’m very glad I saw this one. And I hope I get to write more when I see it again someday. That was my favorite new musical, of all I saw in 2018.

* * *

My favorite comedy, out of all I saw on stage in 2018, was Harvey Fierstein’s classic ode to gay love, “Torch Song,” which ran from November 1st, 2018 to January 6th, 2019 at Broadway’s Helen Hayes Theater. For me, it was the most richly rewarding comedy to play in New York this past year. (The producers have announced there will be a national tour, starring Michael Urie–who’s starred in this season’s Broadway production–beginning in Los Angeles in the fall.) There were some imperfections in the production, but I had very good time.

In going to see “Torch Song,” I felt like I was visiting a valued old friend whom I hadn’t seen in several decades; the friend had changed a bit, of course, with the passing of the years; but there was still a fondly remembered, unchanging essence. And I warmed to the company.

Torch Song Playbill

I loved this play when I first saw it in New York (starring Fierstein himself), several decades ago. It was a groundbreaking, trailblazing play. Fierstein has considerably reworked the material for this production. It doesn’t feel quite right to call this production a revival; too many changes have been made for me to label this production a revival. And yet it is not quite a new play, either; so much of the warmly remembered original core material is still there. It is a significantly revised version of a play–set in the 1970s and early ‘80s–that had a lot to say when it was new, and still has a lot to say today. I’ve been a tremendous admirer of Harvey Fierstein as a both a writer and a performer, since he first came on the scene. I’ve enjoyed him on stage, on screen, even doing stand-up comedy in clubs. (I have wonderful memories of watching him try out material at Erv Raible’s sorely missed club, Eighty Eights, in Greenwich Villege, a couple of decades ago.) And “Torch Song,” in its various incarnations, still remains my personal favorite of all of Fierstein’s many appealing creations.

If “Torch Song,” today, doesn’t have quite the same hard-hitting impact it originally had, it is because–in the years since “Torch Song” first appeared– other plays have drawn inspiration from it and have covered similar issues. It’s partly because gay love–once so controversial–has gained much more mainstream acceptance over the years. And plays dealing with gay themes–once so rare–are now much more common. (In this season, in addition to “Torch Song,” there were two other major revivals on Broadway of plays with significant gay content: “The Boys in the Band” and “Angels in America.”) But it is still funny and bold, and passionate, and spawling, and in-your-face, and rich with life. I still find it inspiring.

Yes, it made me laugh a lot. Fierstein has always known how to write witty zingers. But more importantly, the play has heart. You care about the characters. Fierstein makes you feel the humanity of each of them. He writes with tremendous passion. And he writes with insight. You can’t ask for much more.

Torch Song

This production’s cast isn’t quite as perfect as the one I saw years ago. Fierstein is a unique performer; he owned the role of “Arnold Beckhoff,” which he originated. And I haven’t seen anyone over the years who can match his performance in that role. (And friends of mine have tried. Cas Marino starred in the last little revival in New York.) But I succumbed to the charms of this exceptional play once again–even if I did miss seeing Fierstein himself on the stage. He’d be too old to play the role now, nearly 40 years after he first played it. But he wrote the piece for himself, and it fit him perfectly.

Let me tell you a bit about the history of this play, because I think it is relevant. And it’s a reminder, too, that although “Broadway” is what people think of first when anyone speaks of theater in New York, so much that is important and lasting in American theater actually starts out off-Broadway or even off-off-Broadway in New York. And “Torch Song”–a brilliant and influential work–was born off-off-Broadway.

It didn’t attract much attention at first. And it only got a chance to develop because there were some courageous independent producers, working on the fringes of the theatrical community, who recognized the strengths of a then-largely-unknown Harvey Fierstein and took a chance on him. Fierstein’s early champions deserve recognition, as well as, of course, Fierstein.

The play now known as “Torch Song” started out as three separate one-act plays by Fierstein–“International Stud,” “Fugue in a Nursery,” and “Widows and Children First”–capturing a lonely, needy, awkward, and somewhat-naive drag entertainer named Arnold Beckhoff (originally played by Fierstein) at different stages of his life. Fierstein eventually combined these three one-act plays into a full-length play titled “Torch Song Trilogy.” (The title was shortened to “Torch Song” for the latest incarnation.)

In the first play (which became the first act of “Torch Song Trilogy”), Arnold falls for Ed, a handsome, ambivalent bisexual man. And when that doesn’t seem to work out, Arnold explores the option of anonymous backroom sex at a bar known as the International Stud. (Incidentally, this was a real gay bar, on Perry Street, one of several gay bars noted for its backroom action).

The scene Fierstein wrote, conveying Arnold’s experience one night in the backroom–was daring, as well as funny–when first presented nearly four decades ago. It remains so today.

In the next play (which became the next act of “Torch Song Trilogy”), Arnold–a bit older–falls in love with a gorgeous young model, Alan, and they begin a life together. And Arnold has figure out how he feels about a bit of infidelity on Alan’s part.

In the third play (the final act of “Torch Song Trilogy”), we see a slightly older, wiser, Arnold, trying to cope with life after the death of Alan, and trying to raise a 15-year-old gay foster son, David, whom Alan and he had had hoped to raise together. Ed is coming back into his life in this period–and so is his formidable mother, with her sharply expressed prejudices against homosexuality.

Fierstein was not a well-known “name”–as either a writer or a performer–when he created this material. He had appeared in work, in small theaters, by playwright Robert Patrick (who certainly believed in him) and by himself. And he had won some admirers among adventurous gay male theater-goers, who liked checking out shows on the fringes of the theater community. But he was not yet known to mainstream audiences. And the material he was creating was considered too far “out there” for commercial producers of the time. They would have assumed that a play depicting anonymous sex in the backroom of a Greenwich Village gay bar might only interest guys who were into that scene.

“International Stud” first saw the light of day at La MaMa E.T.C., Ellen Stewart’s terrific off-off-Broadway performance space. Stewart was always willing to give new voices chances to be heard. (I’ve seen fascinating work at LaMaMa, and loved Stewart’s passion for giving outsiders chances to be heard. If you spoke to her, even briefly, you could tell she was the real thing; she totally believed in giving new voices chances to be heard.) “International Stud” opened at La MaMa on February 2, 1978 and ran for two weeks. Stewart herself had some reservations about the piece, but felt it deserved to be seen. That two-week presentation at La MaMa, off-off-Broadway, led to an Off-Broadway production of “International Stud,” a few months later, at the Players Theatre, where it ran for about nine weeks.

Ellen Stewart next presented “Fugue in a Nursery” for a brief run at LaMaMama in February of 1979. She thought it was wordy–but she could feel the life in the work. And so could producer John Glines–an important pioneer of gay theater (his theater company, The Glines, broke a lot of ground)–who presented the first production of the full-length “Torch Song Trilogy,” off-off-Broadway at the Richard Allen Center, uptown, in October 1981.

In January of 1982, Glines moved the play to the Actors’ Playhouse, Off-Broadway, on Seventh Avenue in Greenwich Village, where it ran for about three months. Cast-members included Fierstein as Arnold, Joel Crothers as Ed, Paul Joynt as Alan, Matthew Broderick as David, and Estelle Getty as Mrs. Beckoff. Glines (who was then writing for the “Captain Kangaroo” television show to pay his bills, if memory serves) took justifiable pride in the production; it was not just good theater, it was part of the emerging gay-liberation movement. He hoped it could help people become more understanding and accepting of homosexuality.

In June, Glines –who once told me he was pouring every dollar he made at his day job into this production that he so strongly believed in–moved “Torch Song Trilogy” into Broadway’s Little Theater (now known as the Helen Hayes Theater) on 44th Street. And, to the surprise of many commercial producers, it found a big mainstream audience.

It ran for an incredible 1,222 performances–about three years! I remember seeing so many older women in the audience and wondering how many of them were there simply because they’d heard it was a good play, and how many were there because they wanted to better understand a gay or bisexual son or grandson, or nephew or friend, or husband. The play was funny and touching, and real–but it was also making an important point that was not being made on TV or in films back then: that a gay man might have the same yearnings, for domestic life with a partner and a son, that a straight man might have. I’m sure the play helped educate–not just entertain–many in the audiences back then. When “Torch Song Trilogy” first appeared, it served an educational function that–at least in the New York area–is no longer needed. (At least, not anywhere near to the degree it was needed four decades ago.) People are more understanding of homosexuality these days.

“Torch Song Trilogy”–as produced on Broadway in the early 1980s–was sprawling and talky–and more than four hours long! It is amazing, when I think about it, that a gay-themed play with a running time of more than four hours could have become such a huge hit. But it was filled with life–as the latest incarnation is. When Fierstein adapted “Torch Song Trilogy” for the screen in 1988, he cut it down to about two hours; the streamlined adaptation moved much faster–and I loved the film for what it was; and I have a copy on DVD that I rewatch with delight–but much valuable content was lost in the cutting. The latest stage version, which I enjoyed greatly, is about two hours and forty-five minutes in length.

The play “Torch Song Trilogy” established Fierstein. He won Tony Awards for both his acting and his writing. And I certainly remember the way producer John Glines made history when–in his Tony Award-acceptance speech–he acknowledged his lover, co-producer Larry Lane. That was the first time I ever heard anyone, in a Tony acceptance speech, acknowledge a gay lover.

I was proud of him then for doing that. It took guts! But he was making a statement–as a professional and as a person–just as Fierstein was making–that gay people are just like everyone else. It needed to be said then.

As for the latest stage version, I enjoyed “Torch Song” very much. I laughed all over again at lines I recalled from years ago. There was Arnold Beckoff, who made a living as a drag entertainer and, thus far, had not been too lucky in love, telling us: “I think my biggest problem is being young and beautiful…. It is is my biggest problem because I have never been young and beautiful. Oh, I’ve been beautiful. And God knows I’ve been young. But never the twain have met. Well, not so’s anyone would notice it anyway.”

Torch Song

I found myself getting pulled into Beckhoff’s world easily enough. We can all relate to his insecurities, his self-doubts, his quest for love. And the play grows stronger as it goes along. We are just getting to know him, at first. We share in his happiness, and his sadness. And are surprised when he fights with his Mom–serving, in part, as a stand-in for all who may be intolerant of homosexuals–and more than holds his own. It is a victory for him. And the play ends on a quietly optimistic note; things are looking up in his life, in his relationships with the man he loves, the son he will be adopting, and his mother.

There are very good actors in the production. Mercedes Ruehl, as the mother who has been raised with certain views towards homosexuality and feels she’s to old to change–was first-rate. I liked Michael Urie, starring as Arnold Beckhoff, but have some reservations about his casting, which I’ll get to in a minute. Michael Hsu Rosen (so adorable) as Alan, Jack DiFalco as David, Ward Horton as Ed all acted excellently. I enjoyed their work, and wish I could see the production again. But I don’t think all of the casting was ideal, and I fault director Moises Kaufman for that. The original Broadway production worked better. And I want to give my two cents here.

Harvey Fierstein, in the early 1980s on stage, was the perfect Arnold Beckhoff. He had great presence. He was utterly natural. And at all moments, he was himself. The performance was 100% organic. And tremendously endearing. He used that one-of-a-kind deep, raspy voice of his to sensational effect.

I had not met Fierstein when I first saw him on stage, early in his career. But I found him tremendously likeable. So uaffected. So warm. So human. (Eventually, when I got to meet him in person, I took to him instantly–the warmth, the self-acceptance, the presence all are very strong, and very real. You take to him instantly, on stage or off.)

Now, I don’t usually comment on actors’ physical appearance, but I’m going to say something here because it’s relevant. In Fierstein’s earliest stage appearances, including “Torch Song Trilogy,” he looked sort of rumpled, disheveled, something of a mess. He was not conventionally handsome or pretty, and he was a bit overweight. He must have lost 50 pounds between the time he did the original stage version of “Torch Song Trilogy” and the film version. I don’t know if that was his decision or if some industry professional told him he’d look better on screen if he lost some weight. And I can “get” the desire to appear slim and trim.

But the way he appeared on stage, early in his career–a bit overweight, appearing like he’d never been to a gym in his life and didn’t care–was exactly right for Arnold Beckhof. It made the contrast between him and the great-looking guys he pursued sharp. It fit with his anxiety and insecurity. In a world where looks are so important, he did not even have that going for him.

And that also made it easier for many of us to relate to him. He was an Everyman, not some god on a pedestal. He sounded effeminate at times–so much so that it got a laugh when he’d suddenly talk butch, trying to assert his authority. At all times, he seemed real. As an audience member (and as a gay man who never found time to get to the gym myself), I cheered extra loud when he got the good-looking guy he wanted, because the message was: a good life is possible for anyone. You don’t have to be some toned, trim great-looking guy. You can be an ordinary guy–maybe carrying a few extra pounds–and you can still find love. The play worked even better because Fierstein was not pretty. (By conventional standards, he was better looking in the film version; to me he looked like he’d spent a good bit of time dieting and exercising. He looked great, but part of the play’s original message was muted in the process. If it’s one good-looking guy finding another, the story is not as interesting as it when it’s one not-so-good-looking-guy catching a great-looking guy. As an audience member who was not toned or trim, I liked that latter storyline better. And I liked that Fierstein’s Arnold Beckhoff seemed so clingy, and needy, and gentle. That message, that you didn’t have to be some straight-looking, straight-acting, secure macho stud for life to work out, was powerful.)

All of the actors in the latest stage production of “Torch Song” struck me as equally trim. All are good-looking by conventional standards. All appear to be around the same age. There are not the sharp contrasts the play requires for maximum effectiveness. The actors playing Arnold, Ed, Alan, the foster son David all looked great–like they could all be friends who’d want to share a house on Fire Island together. Harvey Fierstein, when he first did “Torch Song Trilogy” on stage, looked like something of an odd duck–an endearing, lovable ugly duckling. And when life turned out well for him, by the play’s end, it sent a powerful message for all of us in the audience: you don’t have to be some trim, handsome guy for everything to work out.

I liked that. I might say I needed it, when I first saw the play, almost four decades ago. Some of that message has been lost by casting an actor as trim and conventionally good-looking as Michael Urie in the lead.

Torch Song

Don’t get me wrong; I like Michael Urie. I liked all of the actors in the play. But Fierstein, in the original play, was sheer perfection. (And when a character asked him if he had a cold, it made sense because of Fierstein’s unusually raspy voice; the line doesn’t make so much sense now, when asked of Urie, who has a more conventional voice.) And while the actor playing David is terrific, he does not appear remotely like a 15-year-old (the character he is playing); he appears to be in his 20s, like Ed or Alan. And that does not serve the play.

That’s my two cents. I don’t envy any actor having to follow Harvey Fierstein in the role of Arnold Beckhoff. And I’m hard to please. But I enjoyed the play a lot. And as a playwright, Fierstein gives each character his due. Each one has insights to contribute. I like that a lot.

There’s much to love about the production. Even the choices of music were outstanding–from “Cooking Breakfast for the One I Love” (which Billy Rose wrote for his then-wife, Fanny Brice) to Irving Berlin’s “What’ll I Do?” (as poignant a ballad as has ever been written). Heck! I was even enjoying the pre-show music as my friend and I took our seats–there was the recorded voice of young David Cassidy, preparing us for a play that begins in the 1970s….

I wish “Torch Song” could have run longer in New York. But I’m glad it’s going to tour. And I’m glad it’s going to play Los Angeles. Maybe some movie producer will be wise enough to see it could be remade as a film now. I’m old enough to remember when the play became a hit in 1981, and the talk in the entertainment world was that “Torch Song Trilogy” was going to be made into a film starring either Richard Dreyfuss or Dustin Hoffman. (Harvey Fierstein, do

you remember when those rumors were going around? Because Hollywood’s first reaction was the film would need to have a “name”? Even though Dreyfuss and Hoffman–as talented as they are–could not have done justice to Arnold Beckhoff.) But Fierstein, thankfully, got to star in the film, along with Matthew Broderick and Anne Bancroft–sublime casting, all around. And the picture, also featuring Brian Kerwin, Charles Pierce, and Ken Page, as I recall, captured the essence of the play. I’ll watch it again on DVD this week.

Incidentally, the Helen Hayes Theater (formerly known as the Little Theater) looked rather shabby when “Torch Song Trilogy” ran there in the early 1980s. It’s recently been renovated. And it looks beautiful now. Done up nicely in periwinkle blue. I never thought that dumpy little theater could ever look so sharp.

* * *

Paper Mill Playhouse’s production of “Holiday Inn” offered rewards a plenty. Oh, I had some reservations, too, which I’ll get to in a bit. But there was much to relish in their spirited production. And I can see this musical becoming a holiday staple for many regional and community playhouses.

The score is rich with gems by Irving Berlin, one of the greatest of all songwriters–”Shaking the Blues Away,” ”Blue Skies,” ”The Little Things in Life,” “Heat Wave,” ”Easter Parade,” “Happy Holiday,” ”White Christmas,” and more. There’s a great deal to enjoy right there.

Holiday Inn logo

For the most part, the production–directed by Gordon Greenberg, who co-authored the book with Chad Hodge–flowed well. They had a couple of excellent lead performers–Nicholas Rodriguez and Hayley Podschun. Plus wonderful Ann Harada in a featured role.. And a few big, exuberant production numbers, choreographed by Denis Jones–including some of his best work to date.

I was skeptical when the Berlin estate first announced plans for a stage adaptation of the film ”Holiday Inn,” because adaptations of classic film musicals often greatly disappoint, and the original 1942 film starred two iconic performers, Bing Crosby and Fred Astaire. But there’s much to love in this musical production. Yes, there are flaws, too. But I had a good time–this is joyous musical theater. And the whole audience got caught up in the spirit of thing. (By chance, there was a college-age singing actor seated near me, Mike Lang — born long after these Berlin songs were written. But he was as enthusiastic about the show as anyone; the sheer showmanship of the production and the wealth of appealing Berlin melodies worked its magic.)

Paper Mill’s production, which I caught on opening night, was well rehearsed, executed with flair. And some of those great Irving Berlin songs are as good as anything in the canon. (It seemed bizarre to me that Berlin–who’s responsible for most of joys to be found here–got a shorter bio in the Playbill than the sound designer, the lighting designer, the hair/wig designer, and others. This is his show–his songs, and his concept; he created the original characters and story–and he deserves a more respectful bio.)

Costars Nicholas Rodriguez and Hayley Podschun are both immensely likable–warm and approachable. Wisely, they made no attempts to copy the stars who originated their characters in the famed film, and managed to make the characters completely their own. And we care about them. They’re both good singers–and interesting singers–in their own right. (I’d enjoy listening to either of them on an album.) Rodriguez brings a welcome touch of vulnerability to the role, and makes it easier for us to feel for his character. (Crosby was one of the all-time great vocalists–an impeccable popular singer–but he never seemed particularly vulnerable; he could be a tad aloof, distant. Rodriguez shows his feelings more; and that makes it easier for us to relate to him.) Podschun, whom I’ve seen in a number of other productions in New York and at Paper Mill, finally gets a chance to fully show what she’s capable. She’s perfect for this role, with an appealing mix of wholesome, small-town innocence and brass. She’s got character, she’s got strength, and she’s first-rate singer. I liked those two lead characters a lot.

Holiday Inn

Ann Harada–whom I’ve loved since the original production of “Avenue Q”–finds all of the comedy to be found in her supporting role. And has great presence. She’s a strong asset. Jian Harrell, making his professional debut as the bank’s messenger boy, is wonderfully funny. Jordan Gelber was a treat as the agent.

I wasn’t that crazy about the secondary leads, Jeff Kready and Paige Faure. Kready is a solid dancer, but he has to compete with the memory of the peerless Fred Astaire–who was not only distinguished as a dancer, but also as a song stylist, and possessed great personal charm. You simply took to Astaire, even if his character seemed to be, for a moment, acting like a cad. Kready dances well–and it’s thrilling to see the famed Astaire dancing-with-fireworks business “live” on stage–but he hasn’t claimed the part as his own as fully as one might hoped. Nor has Faure. They’re fine, but not as individualistic as you might like. (And, in fairness, their parts aren’t as fully written as they should be. They are pretty much stock characters here. A show works better if we get some feel for characters as people.)

For the most part, the orchestrations by Larry Blank are excellent. And for the most part, the choreography by Denis Jones, is engaging. And yet, the show isn’t quite as rewarding as it could be, or should be. If I were grading it, I’d give it a fine, strong “B.” But not an “A” or an “A+” (which a top musical like “Hello, Dolly!” or “Gypsy” would warrant). I had a very good time.

I could overlook most of the shortcomings in the show. But they’re there. And they deserve some comment.

In contrast to the original film, the pacing isn’t always quite right. The original film had a near-perfect balance of dialogue, small numbers, and big numbers. The Berlin film musicals were almost always well-paced, and often featured dialogue underscored by attractive Berlin melodies (sometimes songs sung elsewhere in the film, sometimes songs heard only as underscoring of essential dialogue scenes).

This show is stuffed–actually over-stuffed at times–with songs, at the expense of a dialogue. And sometimes it feels a bit awkward, like they’re cutting short a conversation that wasn’t fully developed so that they can hurry to an obvious song cue and sing a familiar, famous song that has been forcefully shoehorned into place. Sometimes it felt more like a parade of song hits than a musical.

Holiday Inn at Paper Mill

No one loves Berlin’s music more than I do. But the creators of this stage adaptation have tried to jam too many well-known songs into the show. I think that cutting a couple of the songs, and letting characters talk a bit more would give the show a more natural feel, and give it some needed moments to breathe. And help us bond more with characters. And if you want to add a song to express the characters’ feelings, pick the very best songs for the scene–not just the best-known songs.

“It’s a Lovely Day Today” is a perfectly lovely song from the hit Berlin musical “Call Me Madam.” It belongs in “Call Me Madam.” It doesn’t belong in this stage adaptation of “Holiday Inn.” It’s highly familiar. It doesn’t add anything here. I swear, when people do a “new” stage musical with a score made up of songs by a master like Berlin or Gershwin or Cole Porter, they often try to cram in as many of the songwriter’s best-known songs, whether they fit the show well or not. Berlin wrote over 1200 songs, including some very good “unknown” songs. There are high-quality unknown songs that might fit scenes much better (and provide more rewards for audience members) than overly familiar numbers like “It’s a Lovely Day Today.” But the producers need to seek out people who really know the songwriters’ catalogues, or we’ll just keep recycling the same obvious choices.

Sometimes the show simply feels like it’s trying too hard. There is much to love in the choreography–and the jump-rope bit, in particular, works brilliantly. (The audience burst into applause for the rope-jumping.) But there are also some effects that feel strained or don’t quite work. I didn’t care for the tap-dancing-with-pails-on-the-feet; when you have a song that is pure gold, in terms of music and lyrics, a gimmick like that is only a distraction. Trust the basic material. If you have a song as great as “Shaking the Blues Away,” you don’t need to go for a cheap laugh by tap-dancing with pails on your feet. Let audiences savor the song.

Berlin picked carefully the songs for his films. In the film of “Holiday Inn,” he included a great old number of his, “Lazy.” It’s not in the score of this production. A pity. It’s stronger than some of the material they’ve randomly added.

Berlin picked every note of every song with care. One note is altered, and not for the better, in “Shaking the Blues Away.” Why? Berlin was so particular about such things, and hated such modifications.

The song “Easter Parade” was written to be performed with a grace and an ease, and a lilt–and works best that way. In this stage adaptation, “Easter Parade” winds up taking on a hard-hitting, high-pressure feel, as if the audience is going to be machine-gunned into submission. The number works. But would have worked better had Berlin’s original intentions been honored more.

Don’t get me wrong. There are many rewarding moments in this production–good performers doing good songs, and a heartwarming story. And some zesty, big production numbers. The flaws don’t ruin the production. It’s a big musical, attractively mounted. And the show works for all ages. There wasn’t a better holiday show in the region this winter.

But this could have been a much greater musical. And that’s the pity.

I hope that other Berlin film musicals, from “Blue Skies” to “Easter Parade,” might find their way to the stage. But creating a great stage musical requires balancing all of the elements well. And that ideal balance hasn’t quite been found here.

* * *

I wish I could have had a chance to meet director/choreographer/co-producer Bethany Dellapolla to tell her how much I enjoyed her production of “Zombie Prom” at the Vineyard Theater, but I’ll take a moment to say a few words here.

Sometimes I feel like I’ve met socially, however briefly, seemingly everyone in the theater community. And in most any show that I’ll go to see there are company members who are friends or acquaintances of mine (in this production, I happen to know both the music director and the leading male actor); but I’ve never met Ms. Dellapolla and there was no bio of her in the program, so I’m afraid I can’t tell you anything about her. But she’s taken a big group of youths and molded them into an exuberant, cohesive company–NextGen Youth Theatre–and presented them in a bright, colorful production of “Zombie Prom” that was good medicine from start to finish. The actors’ sheer joy in performing was contagious.

I’ve always liked this musical, written by John Dempsey and Dana P. Rowe (and adapted by Mark Tumminelli). It’s good camp fun, with some plots twists so old they’ll be new to youths of today (one key plot detail–which still works–actually was old-hat when it was spoofed by George M. Cohan in his “George M. Cohan Revue” fully a century ago). Dellapolla and her co-producer/music director, Magnus Tonning Riise, put together a good cast (with Erich Schuett, Olivia Hadad and company) to bring it fully to life.

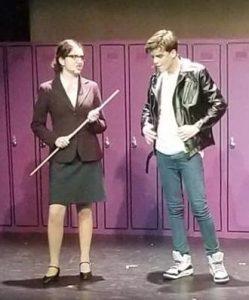

Olivia Hadad and Erich Schuett in Zombie Prom

I had a great time. And parents looking for a program to give their kids some experience in theater might do well to consider NextGen Youth Theatre. It joins Wingspan Arts, TADA Youth Theatre, and a few others, in aiming to educate kids in theater, while allowing them chances to enjoy from themselves and learn from their elders.

I don’t review youth-theater productions the same way I review adults’ productions. Youths, after all, are still learning a lot. But once in a while, I’ll see youths in shows whose promise is evident. Long before Ansel Algort made his mark in such films as “”The Fault is in Our Stars” and Baby Driver,” or Timothee Chalamet gained notice in “Call Me By Your Name,” for example, I took note of them in reviews, in this column, of their high-school work.

Zombie Prom

And both Erich Schuett (who did the national tour of “The Sound of Music” and has recorded with me) and Olivia Hadad who had impressed me previously in youth productions of “Bye Bye,Birdie” and “Heathers”) hold the stage with confidence, ease, and charm. And director/choreographer Dellapolla got a dozen singing/dancing kids to fill the Vineyard Stage with terrific energy. It makes me feel good about the future.

— CHIP DEFFAA, January 6, 2019.

Leave a comment