ON THE TOWN with Chip Deffaa … for November 13th, 2016

I always like visiting Hofstra; they often do good work there. I don’t think they get the recognition they deserve. Their theater department is not as well known as the theater department at NYU; but I’ve seen some fine performers of comparable abilities at both schools.

I’m glad I got to experience “The Rocky Horror Show,” directed by Hunter Foster, at the Bucks County Playhouse. It’s the most satisfying, fully realized production of any show that I’ve seen in months. I wish that the whole well-cast, well-directed production–starring Kevin Cahoon as the cross-dressing, pansexual mad scientist “Frank ‘N’ Furter”–could be transferred to New York City for a commercial run.

It’s the production of “Rocky Horror” I’ve always hoped to see. They’ve got the tone just right. It’s funny, sexy, camp, and ever-surprising. The energy is extraordinary throughout. And the whole thing feels fresh and spontaneous–even when they’re uttering lines I know by heart. New York City could sure use a production like this, whether it were mounted in a large Off-Broadway space or even in a moderately sized Broadway house (like the Nederlander).

Everything that Fox Broadcasting got wrong in their recent, disappointing television adaptation (“The Rocky Horror Picture Show: Let’s Do the Time Warp Again”), the producers at the Bucks County Playhouse have gotten right. There’s an edge to this production, and a hipness.

And Kevin Cahoon was born to play this role. He’s got the charisma, the playful sexuality, and the ability to seem wholly contemporary, yet connected to the best of old-school show business.

He also has something few actors have–a natural flair for ad-libbing. (He demonstrated that well when he brilliantly succeeded John Cameron Mitchell in the original New York run of “Hedwig and the Angry Inch”). It adds to the fun of this production that he is liable, if it fits the moment, to say anything that occurs to him.

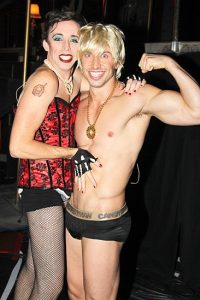

Kevin Cahoon and Katie Anderson

The production feels unpredictable. And that hint of unpredictability–which was missing from the recent Fox television production (overseen by Kenny Ortega, of “High School Musical” renown) and also from the last Broadway revival of “Rocky Horror”–is just as essential to this property as it was to “Hedwig.”

Let me be clear. I liked the last Broadway revival of “Rocky Horror,” which I saw repeatedly at the Circle-in-the-Square Theater, about 15 years ago. (And I even attended the recording session for the original cast album.) That production was certainly better than the recent television adaptation–much better. But still, something vital was missing. The production felt, at times, just a little too tidy, too neat, too pat, too buttoned-down. There were some really terrific actors in the production, and some great moments; there really was a good bit to appreciate. And it was highly polished. But in that production, the inherent wildness of the show had been somewhat tamed; the show felt, at times, slightly compromised.

Here’s one small example. The producers of that last Broadway revival hired Dick Cavett to serve as the production’s narrator. Now Cavett is a likeable guy. And he’s a celebrity. I’m sure his name sold some tickets. He’s wry, urbane, sophisticated; if PBS were doing a tribute to Noel Coward, he’d be an excellent moderator. But he’s utterly non-threatening, and he’s mainstream and establishment. The ideal narrator of “Rocky Horror” should not be urbane, sophisticated, mainstream. There has to be a hint of wildness in his eyes. He should not quite seem like a normal guy… but perhaps more like an escapee from an asylum for the criminally insane who’s trying as hard as he possibly can to act like a normal guy. Cavett brought with him an air of better-quality television–which is pleasant enough in its way; but it is not the ideal tone to set for a show as subversive as “Rocky Horror.” The narrator for the Bucks County Playhouse production played the part just right–his energy was high with a slightly manic overtone; he narrated grandly, eloquently–while making you feel that at any moment he just might leap from that stage and mess with you. From the first moment that the showmanly narrator of this production began talking, I felt sure the material was in just the right hands. The narrator of this production, William Youmans, is a veteran of countless Broadway shows, from “The Little Foxes” (with Elizabeth Taylor), to “Billy Elliot,” to “Bright Star.” And he was just perfect–indispensable to the success of the show. He had me from his first words. And everyone maintained the tone he set.

There’s lots of talent in the cast. Justin Sargent–whom I enjoyed so much (as I noted in these pages) when he took over the leading role in “Spiderman: Turn Off the Dark” on Broadway, late in its run–was perfect as “Riff Raff.” Nick Adams, who was one of the stars of Broadway’s “Priscilla: Queen of the Desert,” made a splendid “Rocky.”

Kevin Cahoon and Nick Adams

Stephanie Gibson and Maximilian Sangerman were fine as “Janet” and “Brad”–the straitlaced young couple whose car breaks down one rainy night, forcing them to walk to the castle of “Frank “n” Furter” in search of assistance. “Frank ‘n’ Furter”–determined to have his way with them–welcomes them to his castle, invites them to get out of their wet clothing. And the mayhem begins.

The audience at the Playhouse–armed with bags of props provided by the management–gets to contribute to the show as well. It’s participatory theater. (That’s part of the tradition.) Getting showered with rice, or having people around you shout fervently at the performers (“Slut!”) is all part of the experience.

And Kevin Cahoon–presiding over the festivities, holding the whole thing together–was great fun. (I liked the offhand way in which he spoke of two of his minions, “Eric and Ivanka….”) I’ve always gotten a great kick out of Cahoon’s work, whether he was leading his own exuberant band at CBGB’s, or appearing in “Hedwig and the Angry Inch” or “The Shaggs,” or anything else. I remember him playing a phantom in the last Broadway production of “Rocky Horror”–and understudying the starring role that he’s playing now.

Late in the show, Cahoon sat on the edge of the stage, ala Judy Garland, and began reminiscing about the Bucks County Playhouse, noting familiarly that “young Bobby Redford, Dick Van Dyke, and Grace Kelly” had all performed, in past years, on that very stage. He said he could still smell Grace Kelly. He took off his wig, making himself more comfortable. He commented that he’d gotten some purple glitter in his eye, and it felt to him as if he were viewing the world right now through an Instagram filter. None of that, of course, was in the original script that Richard O’Brien (author of book, music, and lyrics) created. But the moment fit the freewheeling spirit of the show that O’Brien had conceived. And then Cahoon sang the hell out of “I’m Going Home.” He put it over as effectively as anyone could ever hope to put over that song. (I wish there were a cast album.) He stepped down from the stage and danced with an audience member….. And through the course of that sequence, he throughly bonded with the audience. A great moment in the theater–one I’ll long remember.

Kevin Cahoon

For my tastes, they could have called the show off right there, and gone straight into curtain calls; because nothing could top that. For plot purposes, they still had another couple of numbers to go through. And that was fine. But for me, that sequence with Cahoon talking to the audience, and dancing with a member of the audience, and singing “I’m Going Home”was the high point of the night. And at the very end, after the curtain calls, they invited audience members up on stage to dance with the cast to a reprise of the show’s infectious, irresistible “Time Warp.” A terrific show. A terrific experience.

Occasionally during the show, of course, I had to glance down to take some notes. But with this production I hated having to look away from the stage even for a moment, lest I miss something. (I looked down for one moment, and when I look up, there was “Donald Trump” onstage, groping “Hilary Clinton.” Crazy!)

I’d love to see this production given a proper commercial run in New York. Maybe find a non-traditional venue for it. (If it were available, the Liberty Theater on 42nd Street, where I caught the “Ziegfeld Midnight Frolic” a year or two ago, might work. Or perhaps some cavernous former church could make a good setting for a show taking place in a castle.) And schedule some added late shows on weekends. Director Hunter Foster, and Kevin Cahoon and company, really “get” this show. What they’ve done with it–which is simply so much fun–deserves to be seen by a larger audience.

The Bucks County Playhouse

By the way, the venerable Bucks County Playhouse–which has been renovated beautifully–was absolutely jam-packed. I used to see shows there, in the declining years of the previous management (which really ran the place into the ground), and there’d often be more empty seats than patrons in the house. The theater has such a rich history–dating back to the 1930s–and such a wonderful location (right on the Delaware River), I’m very glad to see it making such a great comeback under its new management. Kudos to producers Robyn Goodman, Alexander Fraser, Stephen Kocis, Josh Fiedler, Sharon A. Carr, and the Bridge Street Foundation.

And Hunter Foster, whom I’ve always appreciated as an actor, dating back to his New York stage appearances in “Urinetown” and “Little Shop of Horrors,” is really going great guns as a director these days.

Hunter Foster

* * *

Earlier this season. I was lucky enough to catch another production directed by Foster–“Million Dollar Quartet,” at the Westchester Broadway diner theater in Elmsford, New York. And that, too, was an unexpected treat–carried off with real flair. Written by Colin Escott and Floyd Mutrux and filled with memorable hits (“Blue Suede Shoes,” “Memories are Made of This,” “Fever,” “I Walk the Line,” “That’s All Right,” “Great Balls of Fire”), “Million Dollar Quartet” is an appealing blend of entertainment and history. It’s a jukebox musical, but much better written than your average jukebox musical; there’s a storyline with enough human interest, drama, and historical accuracy to hold anyone’s interest throughout.

Million Dollar Quartet

And there wasn’t a weak link in the cast that Foster put together and directed. I very much enjoyed the contributions of co-stars Sky Seals (as “Johnny Cash”), Ari McKay Wilford (“Elvis Presley”), Dominique Scott (“Jerry Lee Lewis”), John Michael Presney (“Carl Perkins”)–playing the “Million Dollar Quartet” that actually assembled one day, late in 1956 at the Sun Records Studio of Sam Phillips (played well by Jason Loughlin). (Bligh Voth, portraying Presley’s girlfriend of the moment, rounded out the cast.) Hunter Foster certainly knows this show well; he was in the original Broadway cast of Million Dollar Quartet” (playing “Sam Phillips”) at the Nederlander Theater in 2010-2011.

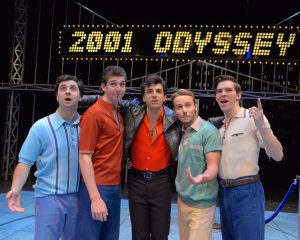

Million Dollar Quartet cast

The action takes place one day, early in the rock ‘n’ roll era. Presley, Cash, Lewis, Perkins have gathered by chance. They talk, sing, voice their hopes and fears for the future.

The actors in this well-directed production wisely resisted, for the most part, any temptations to offer caricatures of the celebrities they were portraying. They offered us, by and large, realistic portrayals of the artists as human beings, with the kinds of concerns any of us might have; we could relate to the difficult choices facing them. Seals, incidentally, evoked Cash so well that it was uncanny; the moment he began talking and singing in those familiar deep, resonant tones–but talking naturally, never exaggerating the way an impressionist would–I felt confident the show was going to work. I liked, too, the down-to-earth way that Ari Wilford underplayed Elvis Presley–a refreshing change of pace from the cartoon-like send-ups that Presley-impersonators typically offer. Dominique Scott’s version of Jerry Lee Lewis may have been slightly more flamboyant the original, but his vivid characterization was such fun (and Lewis could be pretty over-the-top at times onstage himself), I went with it. Presney, as Carl Perkins–bitter that Elvis Presley had stolen his thunder–helped give the show some welcome darker colors.

I’ve seen countless shows at Westchester Broadway over the past thirty-odd years; this was one of the better productions I’ve seen there. I give Foster a lot of credit.

* * *

I recently returned to the Westchester Broadway dinner theater to check out their current offering, “Saturday Night Fever” (directed/choreographed by Richard Stafford), which is booked into January 2017 (with a hiatus in December for a holiday show). There are some good performances and some fun moments–enough for me to be glad I went to see it.

Saturday Night Fever program

But “Saturday Night Fever” is not a very good musical. It’s lightweight, escapist fare. The script (by Sean Cercone, David Abbinanti, Robert Stigwood, Bill Oaks, based on the Paramount motion picture and Nik Cohn’s original “New York Magazine” article) has an uneven, cobbled-together feel. The show proceeds by fits and starts, and songs sometimes feel like they’ve been shoehorned into place.

In a great musical, there’s forward momentum from beginning to end; dialogue flows naturally into songs. But that’s not the case in this musical. It drags at times. And songs sometimes feel like they’re interrupting the story, not enhancing it.

But I enjoyed several fine performances; the big, high-spirited dance numbers; and some catchy Bee Gees songs, like “Stayin’ Alive” and “How Deep is Your Love.” (There are also, alas, some not-so-memorable songs that seem like filler.).

Saturday Night Fever cast

The leads, Jacob Tischler and Alexandra Matteo–both new to me–rang true and carried the story well. They’re well cast. They really look and sound like they grew up in Bay Ridge. Not like movie stars, but like real people from the Old Neighborhood. And Tischler’s impressive dancing worked. Matteo was perfect as the girl from Bay Ridge with aspirations for something better in life–even if it’s just being a receptionist in Manhattan.

Jacob Tischler and Alexandra Matteo

I got a particularly great kick out of seeing veteran Ray DeMattis–a character actor I always love–make the most of his all-too-brief scenes as the protagonist’s father. (I’ve enjoyed his work since he was in the original Broadway run of “Grease.”) He was, for me, the most interesting performer on the stage, and his moments felt real. He could pause, or repeat a word, and hold you, playing an out-of-work blue-collar guy,.putting down his son to mask his own insecurities. (For me, it was worth seeing this production just to savor his moments onstage.)

Ray DeMattis

And it was fun seeing Chris Hlinka–who’d impressed me in his New York stage debut in a little musical called “Most Likely To”–as one of the protagonist’s buddies. I enjoyed his dancing, too.

But oh! I wish the script of this musical was better. The tone is inconsistent; at one moment the show seems to be aiming for social realism; the next moment it’s trying to razzle-dazzle us with superficial glitz. And the writers don’t know how to build up to an important death scene properly to make us care about it; the death, when it comes, feels melodramatic rather than moving.

Saturday Night Fever

“Saturday Night Fever” is not a great musical. (The movie worked, but the stage adaptation was botched.) I didn’t care for it much in its brief original Broadway run. (Although I was happy, at the time, that some friends in the cast were getting some employment.) But I’ll take my pleasures where I find them. DeMattis was a treat. The dancing in the show is fun. And I hope to see more of Alexandra Matteo in future shows.

* * *

I wanted so much to love “The Producers” at Paper Mill Playhouse. But it was not to be.

The Producers program

I sure loved the original Broadway production of “The Producers,” co-starring Nathan Lane and Matthew Broderick. It was one of my favorite Broadway shows of the best 20 years; I saw it repeatedly throughout its Broadway run. It deserved all of the many Tony Awards it won.

But for my tastes, Paper Mill’s production didn’t quite work–at least, not the way the original Broadway production did. And I left with decidedly mixed feelings. Oh! This big, bright musical was handsomely produced. They tried to copy the original Broadway production as closely as possible. (Don Stephenson was credited with re-creating Susan Stroman’s original direction; Bill Burns was credited with re-creating Stroman’s original choreography.) And it was certainly a pleasure to see again such irresistible production numbers as “The King of Broadway” and “Springtime for Hitler,” just as Stroman so masterfully originally staged them.

The Producers

There are plenty of laughs in “The Producers”; I think the script, by Mel Brooks and Thomas Meehan (based on Brooks’s famed film of the same name) still packs into two-and-a-half hours more effective gags than the script of any other Broadway musical of the past 20 years. And I sure laughed a lot, watching Paper Mill’s production.

But the original Broadway production had more than just laughs. It had pathos, it had nuance, it had schmaltz–and those important “extras” were missing at Paper Mill.

And, of course, the original Broadway production had two of our best musical-comedy stars, delivering star turns. This production had competent players in the lead roles, skating over the surface of the material in a highly professional fashion. Which is not the same thing.

The actors in this production playing the two main roles–Michael Kostroff as “Max Bialystock” and David Josefsberg as “Leo Bloom”– did a decent job; they hit the laugh-lines hard (sometimes too hard) and they got plenty of laughs. I liked them. But there were moments when they seemed to disappear into the ensemble on stage. They didn’t have enough presence. And their characterizations were more one-note than those created by Lane and Broderick in the original Broadway production. Playing producers striving to make money from a flop, they came across as ambitious schemers. But I didn’t feel for them, connect with them, root for them, like I should have.

Matthew Broderick’s performance on Broadway was beautifully layered, so we sensed his character’s gentle pathos, no less than his ambition. And Nathan Lane, playing a crooked producer whose “glory days” were never all that glorious, was a most endearing crook. That “endearing” quality is missing in the Paper Mill production, and that makes a huge difference. For me, this production lacked heart. It was fast and funny and slick. But disappointing. Had I never seen the original Broadway production, I might have left Paper Mill Playhouse with fewer complaints–because there was a lot to enjoy. But the original Broadway production showed us what this musical comedy really could be. And this Paper Mill production felt, at times, like a pale copy.

Among the supporting players, I thought John Treacy Egan’s performance as the demented playwright, “Franz Liebkind,” was right on the money. (I enjoyed his performance as much–or more than–any other performance in the show.) And Kevin Pariseau and Mark Price had their moments–good fun–as director “Roger De Bris” and his “common-law assistant,” “Carmen Ghia.”

But I was really hoping for more from the production as a whole. It’s a laugh-filled show. But there’s more to it than the director and stars gave us. I felt, at times, like I was watching a roadshow version of the original.

* * *

For me, Patrick Rinn’s charming–and honest–autobiographical show, “I Never Promised You a Rose Garden” (at the Triad, in Manhattan)–was a delight. . I enjoyed every open-hearted minute of this unpretentious show. The stories he told were entertaining, and easy to relate to. And he has edited them down with wonderful precision; there’s not an extraneous word–no fat that needs to be trimmed. And that’s rare. He delivered an hour-long cabaret show that left me wanting more. There’s some singing and dancing, and lip-synching with flair. It’s a warmly recommended show. I hadn’t felt like going out–I was under the weather that night–but Rinn’s show was a tonic! I enjoyed the stories he told of growing up, and gradually figuring out he was gay, and drinking too much, and never wanting to be alone. He made himself vulnerable on that stage, which takes courage. And that drew us close to him. The sharing–not just the singing and dancing–made the night really work. My guest and I both had a great time, and felt like we were getting to know him better. A well-done cabaret show.

Patrick Rinn

Rinn made it all look very easy. But cabaret shows this satisfying are rarer than they should be. There’s no shortage of good singers. But there’s a shortage of good cabaret shows. A good show is more than just offering songs. It’s connecting with an audience–and hopefully touching an audience–through both spoken words and songs. And Rinn did that.

It was also great to see that master song-and-dance man Tommy Tune in the house, and say hi to him afterwards. It always makes me feel good to see Tommy Tune. That man generates so much positive energy.

* * *

I don’t comment on every show I see in these pages–only select shows. And I certainly don’t comment on every college show. But throughout my career, I’ve always enjoyed checking out college shows when time allows. Even during the many years when I was so busy reviewing for the New York Post and for Entertainment Weekly, and going out almost every night, I always found time to see the rising talent at colleges and conservatories–NYU, Wagner, Pace, Juilliard, AMDA, Princeton, Hofstra etc. (Clive Barnes, the distinguished longtime theater/dance critic of The York Times and New York Post, taught me the value of looking for upcoming artists-to-watch, of making an effort to see the rising generation.) I’ve had the pleasure of spotting talented then-unknown guys and gals, as students, who went on to success on Broadway and in Hollywood. (I’ll see a performer on Broadway these days like Tony Award-winner Nikki James, and remember first meeting her when she was an undergrad at NYU.)

The other night, I made a last-minute decision to catch the musical comedy “Little Shop of Horrors” (directed by Jennifer L. Hart) at Hofstra University, and I’m glad I did. Well-cast, well-directed, and lots of fun. The energy was there. The overall feel for this production of the witty musical comedy by Howard Ashman (book and lyrics) and Alan Menken (music) was right. All of the actors playing spoken parts did good jobs.

Little Shop of Horrors, Richie Dupkin.

And the various puppets representing the ever-growing man-eating plant (“Audrey II”)–such an important part of this show–were handled in a first-rate way, as well as I’ve ever seen it done anywhere. I respect that professionalism, which you don’t always find at the college level. Throughout the show, the puppet always seemed like a living creature, and I want to compliment everyone who made that possible, from Peter Charney (seen in the photo), who directed the puppet work, to Mason Sansonia, who provided the resonant voice, to puppeteers Lyndsay Crescenti, Roseanna Zeramo, Lisa Delia. (When that puppet tilted its head just so, and paused exactly the right length of time before answering “Well…”–after being asked if it would settle for some roast beef instead of human blood–it was as important a member of the cast as any humans seen on stage. It felt like a Jack Benny moment. Nicely done.)

Little Shop of Horrors

There was not a weak link among any of the spoken roles in the production. With a bit of polishing (to bring the dancing by the Skid Row gals up to New York standards), you could–theoretically–put the production on the road in a non-Equity tour, or present it in any festival, and audiences would be happy.

Richie Dupkin was totally believable as the shy, bumbling, hapless “Seymour,” working as an assistant in a skid-row flower shop, with a crush on his fellow shop worker, “Audrey.” And who knew that Dupkin could dance like that? His dancing–goofy, eccentric, fascinating, original and wholly in character–was a most welcome surprise. A high point of an appealing production, and totally unexpected. (I wanted the little dance to last longer.) Aside from participating–as a member of the ensemble–in the memorable bottle-dance in “Fiddler on the Roof” last year, he hadn’t really danced much in any show I’d caught before. (At least, not in my memory.) And I’ve seen a good number of Hofstra shows. Kudos to him and to choreographer Jack Saleeby! I was impressed–and I’m not easily impressed by dancing in college shows. (Incidentally, that one dance would make me take note of Saleeby as a choreographer, if I hadn’t already done so, because it was original, expressive, and suited so well the personality of the character.)

Photo: Jonathan Heisler, Hofstra University Photographer

Sofie Koloc got well into the spirit of the sweet/sad, lovesick/masochistic “Audrey.” She understood the character well, endeared herself to us, and caught every laugh. (I loved her tacky clothes, as well; costume designer Meredith R. Van Scoy scored.) And Dupkin and Koloc–playing those poor starcrossed lovers–sang well together on their lilting lovesong “Suddenly Seymour.” Andrew Salzano was rewarding as “Mushnik,” the shop-owner, exuberantly offering to adopt “Seymour” (and at one point, scooping him up in his arms like a child–a nice touch).

The strongest, funniest work was offered by Justin Chesney. He really nailed it, playing multiple roles with great show-stealing panache. A vivid stage presence. I’ve enjoyed his work before, both at Hofstra and in one of June Rachelson-Ospa’s children’s musicals in New York City (“Rapunzarella White”), but I did not realize he was this good. He performed with tremendous flair, and great comic timing. He’d be an asset to any show, and I look forward to seeing more of his work. Of course, you can spot in any performer areas that could stand improvement. Occasionally, playing various characters in the second act, some of Chesney’s words were garbled; I simply could not understand them (which is a fairly common problem in college shows, and among young actors generally, as any director can tell you). When you’re speaking quickly, playing a character with a strong accent–as Chesney sometimes had to do in this show–it’s essential to take extra care to articulate clearly. And directors, who know scripts so well they may not always notice if actors aren’t articulating clearly, should always bring in to final rehearsals some people who don’t know the show at all, and have them sit in different parts od the house, just to see if they can make out all of the dialogue.

Justin Chesney

It made me happy to unexpectedly run into talented actors I’d enjoyed in past Hofstra productions–like Will Ketter and Noah Smith–before the show. On balance, a very good night.

I always like visiting Hofstra; they often do good work there. I don’t think they get the recognition they deserve. Their theater department is not as well known as the theater department at NYU; but I’ve seen some fine performers of comparable abilities at both schools. And if I see a good performer, anywhere, I always make a mental note. Who knows? Someday I might be directing a show with a role just right for him or her. For example, I recently invited a gal I’d seen in “Rent” at Hofstra four or five years ago to record for me; I had a song that I felt would be just right for her particular gifts; and now–four or five years after I first saw her, and a few years after she’s graduated from college–she’s going to be on a future album of mine. I think, too, of one fellow who worked for me as a publicist for a while–Solomon Singer. He turned out to be just as good at PR in the theater world as he was at dancing. I first met him on a visit to Hofstra some 15 years ago, when he was a student there. You never know.

If you’re working on a college show–or any show, anywhere, that the public is invited to see–you always want to do your best. You never know who in the industry is seeing you, taking stock of what you can do. I give that same advice to actors, by the way, every time I direct a play. (And it’s good for all of us to remember.) I remember telling the actors that, some years ago, when my show “George M. Cohan: In his Own Words” was about to open for an Equity Showcase run on 42nd Street. I knew that industry friends of mine, from Matthew Broderick and Sarah Jessica Parker, to choreographer Mercedes Ellington and comedian Soupy Sales, along with several agents, were coming that night. And they did come. And so did a representative of Samuel French Inc., the world’s oldest play-publishing firm; I didn’t invite him or know he was coming; I was totally surprised when he introduced himself to me after the show, and offered to publish the play. The next thing I knew, the play was published. You just never know who is seeing your work.

* * *

I enjoyed so much Hofstra’s production of the musical comedy “Little Shop of Horrors,” I decided to also check out their production of Anton Checkhov’s 1903 masterpiece “The Cherry Orchard” (English version by Tom Stoppard). This timeless, challenging drama, with a large all-student cast, was directed with care and understanding by veteran pro Peter Sander, who recently retired from the Hofstra Department of Drama and Dance. I’ve always loved this insightful and powerful play. It is far from easy to carry off. If some of the roles ideally call for seasoned actors with far more life-experience than any college student has had, I think it’s good for aspiring actors to stretch by performing great dramas such as Checkhov’s.

In “The Cherry Orchard,” Checkhov was ostensibly writing about one upper-crust family that has fallen on hard times. In the course of the drama, we see the family lose their grand estate; and as their fortunes have declined, the fortunes of a former member of the peasant-class have risen. Checkhov was seeing larger trends in Russian society; his perceptive work showed us a culture in change—with people caught up in currents they did not always understand. Sander staged this well in a black-box theater, with audiences on three sides. And when, late in the play, all members of the large cast gazed in different directions–looking outward, uncertain about the futures they faced—it was a powerful moment of staging, visually striking as well as perfectly capturing the playwright’s point. I will long remember that. My compliments to director Peter Sander, and to assistant director Max Cerci. The final image of the production is powerful too. The loyal, longtime family servant “Firs” (well played by Michael Mahoski)–who’s been overlooked by his oblivious employers, wrapped up in their own lives—slow, painstakingly lays down on the floor of the home to die.

There were a number of fine performances on the stage. But the performance I enjoyed the most was given by the fellow who, I noted last year, gave the most commanding performance of any fellow I’d seen star in a college musical production anywhere in recent years, Michael Caizzi. I’d likened him to a young Zero Mostel when I reviewed his performance in “Fiddler on the Roof” at Hofstra a year ago. That was a musical, and his strong, warm singing impressed me then. This was the first time I’d seen him in a straight play—and a demanding one at that—and I didn’t know what to expect. But his ease on stage, his hold over the audience, his way of letting layers of feelings show—all of these things impressed me now. Playing “Gaev,” he added much to this production. (And I missed his presence when he was absent from the stage.) He is a natural. I watched his work, appreciatively, with a hunch that when—in years to come–I see him in shows on Broadway and Off-Broadway, and regionally, I’m going to remember the great assurance he demonstrated on stage, even as a college student. He’ll be at home on any stage.

MICHAEL CAIZZI IN “THE CHERRY ORCHARD” Photographer: Jonathan Heisler, Hofstra University Photographer

As “Lopakhin,” Justin Chevalier’s strength, excellent diction and projection, and understanding of his character, impressed, too. I very much enjoyed Bryan Raiton as the arrogant, ambitious “Yasha”—a smaller role, but carried off with finesse. He was perfect in that role. And his body language spoke volumes, even when he did not have lines to say. (College actors don’t always understand—as Raiton clearly does—that you act with your whole body, and you never slip out of character. He was “Yasha”—haughty and pleased with himself—even when he stood silently, facing away.)

I’m looking forward to seeing more of Laura Erle, who was an utter delight—sensitive and sympathetic (my heart opened up to her)—as “Varya.” I enjoyed Lauren Dietzel as “Anya.” And I felt for Claire Romansky, playing “Ranevskaya,” the bewildered, befuddled matron whose life of privilege hasn’t turned out the way she had expected. The life she has known is coming to an end, and she hasn’t the perception or insight to figure out how to make the best of the situation. I admire any college student with the guts to attempt a role so demanding. She caught the essence. But I’d love to see her play the same role again 10 years from now, and 20 years from now, and 30 years from now, when life will have a way of helping her to find nuances in the role she cannot yet sense or convey.

Noah Smith added welcome comic leavening to the mix, as the bumbling “Yepikhodov.” He was great fun. (But he would have been better served had the director had him do that bumping-into-the-furniture business not quite so many times; had it been done more sparingly, it would have paid off stronger.)

Checkhov is good for the soul. And “The Cherry Orchard” has not dated one bit. Its concerns speak loudly to our current situation, as well. I’m very glad I went. (Incidentally, Roundabout Theater is presenting a new production of “The Cherry Orchard”on Broadway, adapted by Stephen Karam; I’m looking forward to checking it out, and perhaps commenting in a future column.)

It’s always a joy to see new talent emerge. And while I’m on the subject of Hofstra, may I offer congratulations to three folk from the Hofstra theater community who are beginning to move out into the larger theater community. Peter Charney and Jack Saleeby (music and lyrics) and Noah Silva (book) have written a new musical, “Bright and Brave,” which is one of 10 plays and musicals (out of some 60 submissions) that will get a premiere public staged reading in the Fresh Grind Festival, at Theaterlab in NYC, in January.

* * *

Whenever I attend a production or a showcase at a college or a conservatory, the one question I’m most likely to be asked by student performers is: “Do you think I will be able to make it in this business?” It’s actually a harder question to answer than kids tend to realize, because having talent is only part of the equation. And in the real world, there will be great competition for every role. Every year, a conservatory like AMDA (the American Musical and Dramatic Academy) will graduate hundreds of students who can sing, dance, and act well. The industry cannot guarantee them all a career. Who will succeed? Who will quickly fall by the wayside? Factors other than talent often prove decisive.

If I can boil down some advice–invaluable pointers I’ve heard from the wisest, most successful people in the business; things that should be taught to every aspiring actor–it would go something like this: Don’t be flake. Earn a solid-gold reputation for reliability. Learn your lines. Always be early. Don’t create drama offstage. Don’t gossip or pay attention to gossip. Learn to recognize good opportunities when they come; know that they’ll rarely come at convenient times; accepting them will often require making sacrifices. Be mature enough, flexible enough, and forgiving enough to work with people you may not like; some of the best directors, writers, producers you will work with will be very rough on you; but if you only want to work with people who are “nice,” you won’t work much, and you won’t work with the best. Don’t give in to fears. More potential careers are short-circuited by fears than by anything else. Every year some talented aspiring actors (and directors and choreographers) will sabotage themselves. As the late, great Fred Ebb once told me, “People get the love they subconsciously believe they deserve, and they get the careers they subconsciously believe they deserve.” Carol Channing taught me that there are some actors who will not let anything stop them from having a career–and they will have a chance at succeeding. By contrast, she added, there are other actors who, subconsciously, will not let anything stop them from not having a career; they will always find excuses not to do the play or be in the TV show or make the recording. Or they will quit the show after they’ve said yes. Or otherwise undermine themselves. And they won’t succeed. Carol Channing taught me that many actors short-circuit their careers because they get cold feet, they give into their fears and self-doubts. She taught me to always expect that if I cast a play or gather singers for a recording, a surprisingly large number of the people who initially say yes will find an excuse to drop out before the play opens or the recording is made. And that I shouldn’t give a second chance to those who flake out like that; they’re not meant for the business. And if, as a director, writer, or producer, I give them more chances… they’ll flake out again and again. If people want to sabotage their careers, she noted, they can always find some seemingly good excuse not to do a play or make a recording. And they will. The phenomenon is far more common than most people realize.

Fred Ebb (of the legendary Broadway songwriting team, Kander & Ebb), making the same point to me in his own way, noted how hard it is, subconsciously, for some people to say “yes” to the opportunities life offers them; if I’m gathering talent, as a director or writer or producer, he told me, I need to look for the people who know how to say “yes” to life.

And I’ve seen this sort of thing–aspiring actors stopping their own careers from happening–again and again. One of the best people saw in any college production of recent years told me last Fall that his dream for the summer of 2016 was to work in summer stock; and when we spoke, he insisted he couldn’t wait for the auditions. But when I touched base with him again some months later, to ask him how auditions had gone, he told me he’d decided at the last minute not to go to auditions but to spend the time studying for his college classes instead; he told me he’d “definitely” do summer stock the next year. Maybe he will. But life favors the bold. I have a hunch he just got cold feet, and that doesn’t augur well for him.

By contrast, Michael Caizzi–who’s impressed me so much playing leads in various show at Hofstra–told me he not only auditioned for summer stock, he wound up starring last summer in “A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum,” in one of the nation’s oldest, most respected summer theaters. So he’s still in college–and he’s already starred in his first professional summer-theater show. And he’s just been nominated for a Broadwayworld Award for his performance in “A Funny Thing.” He’s on his way. The other fellow, who opted to stay home and study for academic courses rather than audition for summer stock, wound up taking a routine summer job entirely outside of theater. Both are very talented singing actors. But if I had to make a bet on who’s more likely to have a career as a performer–or if I had to pick one of them to work with myself–the one who auditioned and did the summer show is already making the right moves. And so much of life depends on making the right choices.

So when young actors ask, “Will I make it,” a lot of times I want to tell them, “That will depend, more than you may realize, on choices you make.” The actors I work with again and again–and I’ll often work with people I’ve known for a decade or more–are people I know are not just talented, but will work with enthusiasm and utter reliability. I wish the colleges and conservatories would take a bit more time to teach aspiring actors just how important qualities like good worth ethics, good attitudes, good character are.

* * *

I’ve always liked to work on multiple projects. I’ve written eight published books, 16 published plays, numerous articles and songs, and I’ve produced 17 albums. I’m love my work, and am proud of it. I’m particularly excited about a couple of albums that should be coming out in the next month or so. One is “The Chip Deffaa Songbook,” a sampling of theater songs I’ve written or co-written over the years. Every time we’ve mounted a production of a show of mine some place–whether it’s “Theater Boys,” “The Seven Little Foys,” “George M. Cohan Tonight!,” “Mad About the Boy,” or anything else–I’ve gotten requests from audience members for such an album. And it should be out, within just a few more weeks. It includes new recordings of songs of mine by some of my favorite performers from the Broadway community, such as Giuseppe Bausilio, Matthew Nardozzi, Beth Bartley, plus older recordings by other favorites of mine, such as Seth Sikes, Jon Peterson, Max Beer. And some special material performed by newcomers I have great belief in, Alec Deland and Gabiella Green. I feel very lucky and very blessed to work regularly with such talented people, and to have them represented on a sampler of my work.

Coming out shortly after that is “Irving Berlin Revisited,” featuring many rare and never-before-recorded Irving Berlin songs, sung by some of my favorite singers from New York’s theatrical and cabaret communities, including Natalie Douglas, Emily Bordonaro, Charlie Franklin, Jeremy Greenbaum, and more. This forthcoming album, and my recently released “Irving Berlin Songbook,” are the culmination of 10 years of research. I’ve carefully gone through every song Berlin is known to have written or co-written, searching for little-known gems. These albums are the beginning of a Berlin series. Eventually I hope to record virtually all of Berlin’s never-before-recorded songs. Berlin is one of the greatest of all songwriters. He was so extraordinarily prolific, some very good songs simply got lost in the shuffle. I’m taking time off from directing for a while, to focus on getting some of the rarest Berlin songs recorded. It’s exciting for me to “rediscover” lost songs of Berlin’s, and shine some light on them. And at the same time, cast some light on singers I believe in. It’s a fun project.

– CHIP DEFFAA, November 13th 2016

Leave a comment