ON THE TOWN WITH CHIP DEFFAA…. Oct. 31st 2015

I’m glad I got to attend the opening night of “The Bandstand”–an intriguing, ambitious, original musical–at Paper Mill Playhouse. Does the show–which some are hoping may eventually go to Broadway–need work? Yes, definitely. Is it worth seeing now? Again, yes, definitely! It’s fresh, bumpy in spots, and occasionally a bit too melodramatic–but it grabbed me from the start, and held my attention throughout. There are some excellent performances. And the energy is great.

Yes, there are flaws that certainly need fixing. The production occasionally made me wince with its little misssteps. But it takes a lot of guts to mount a completely original musical–one that is not adapted from a successful film, play, or book. I salute this show’s newcomer-creators: Richard Oberbacker (book, music, and lyrics) and Robert Taylor (book and lyrics). I salute, too, the Paper Mill Playhouse (Mark S. Hoebee, Producing Artistic Director, and Todd Schmidt, Managing Director), for taking a chance on an unknown work, and mounting it handsomely (with direction and choreography by Andy Blankenbuehler, and scenic design by David Korins). It would have been far easier for Paper Mill to mount still another a revival of an all-too-familiar show. It’s fun to see something brand new.

Watching the show, though, I was reminded of something that the late lyricist/librettist Fred Ebb, whom I greatly admired, once told me. With his longtime collaborator, composer John Kander, Ebb helped give us such immortal musicals as “Cabaret:” (based on John Van Druten’s play, “I Am a Camera” and Christopher Isherwood’s “Berlin Stories”) and “Chicago” (based on Maurine Dallas Watkin’s play of the same name). Since so many things that can go wrong in the development of a musical, Ebb told me, it’s always safest to start with a successful play; that way, you’re assured of having at least a foundation for your show that you know is solid. And if you adapt a successful play, you’ll have some audience-tested lines in place before the first public preview of the new work. Ebb felt there was much to be said for using a time-tested play as a basis for a musical.

Starting entirely from scratch–creating a wholly original story, and developing a brand new book, music, and lyrics–is an enormous challenge; lots of things can go wrong,. and almost inevitably will. Out-of-town tryouts were a great boon to musicals in the old days; many shows were first mounted in New Haven or Boston, or another city (such as Detroit, of all places, in the case of “Hello, Dolly!”), and time was taken, out of town, to do the fixing that appeared necessary if the show were to make it on Broadway. (Not all shows could be fixed, of course; but out-of-town tryouts made it easier to try to at least try to make fixes.)

Paper Mill Playhouse, in more modern times, has become a great place to try out new musicals. Sometimes, a new show mounted at Paper Mill (like “Newsies”) will be clearly ready to transfer immediately to Broadway. (I came home from the opening night of “Newsies” at Paper Mill elated, and wrote that same night that the show needed to go to Broadway ASAP. It did!) Sometimes (as is the case with “The Bandstand”), a new musical might not yet be at that point, although it shows real promise. But putting a new musical up before an audience at a place like Paper Mill gives everyone invaluable help in seeing what works and what doesn’t. As for “The Bandstand,” here’s my take on what worked and what didn’t.

* * *

First, I liked the wholly original storyline. “The Bandstand” is about a group of guys–all of whom have just fought in World War Two–coming together after the war to form a small swing band. They plan to compete in an important national radio competition, which they’re promised could get them a motion-picture contract. These guys are all still feeling the emotional pain they suffered in the war. They all feel damaged to some degree. But their love of music helps them bond, and they’re determined to win the radio competition.

Cory Cott (who’s previously starred appealingly on Broadway in “Gigi” and “Newsies”) plays the driven, angst-filled leader of the group, and he’s never been better. I was wholly satisfied with his work.

Laura Osnes (who earned a Tony nomination for her starring performance in Rodgers & Hammerstein’s “Cinderella”) finds a nice mix of sweetness and strength playing the show’s female love-interest/band singer. However, she’s not ideal for the part. She has a beautiful, legit musical-theater voice, which was perfect for the theater songs of “Cinderella”–but she doesn’t really swing. And when she tries to sound her jazziest, she doesn’t sound “period.”

Cott’s character, in the show, is supposed to really live for music; he stresses that he wants to form the best possible swing band. And he selects Osnes’ character to sing with his band.

Now the best singers of the Swing Era, such as Billie Holiday, Ella Fitzgerald, Anita O’Day, could swing effortlessly on any tune, at any tempo. And so could many, many lesser band singers, from Bea Wain to Jo Stafford to Helen Ward; that was part of the musical air they all breathed back then. There are swing specialists today (such as Ingrid Lucia, Madeline Peyroux, Molly Ryan, to name but a few fine singers) who can swing on any tune at any tempo. But Osnes has a certain degree of musical stiffness that speaks of the conservatory, of musical-theater training. The script has both Cott’s character and Osnes’ character talking about their great love of swing. Osnes in an excellent actress and an excellent singer in her own way; she’d be great for any of the Rodgers & Hammerstein musicals, from “Carousel” to “The Sound of Music.” But a singer who swings more would serve this particular show much better.

I adored the performance in “The Bandstand” of Beth Leavel (who won the Tony Award, the Drama Desk Award, and assorted other honors for her work in “The Drowsy Chaperone”), playing the wise, down-to-earth mother of Osnes’ character. She is absolutely wonderful in a rather small supporting role. She was my favorite out of all the fine players in the generally solid cast–the most interesting. She’s so talented, I wished she somehow could have had more to do (although the story is not about her character)–her stage presence, her timing, her general feel for musical comedy are all first-rate. She commands our attention in her relatively brief appearances in the show.

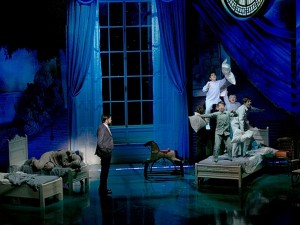

The production drew me into the story right away. Director/choreographer Andy Blankenbuehler staged the first scene very effectively. We see soldiers on the battlefield, with percussive music simultaneously evoking the big-band era (think of the tom-tomming that opens Benny Goodman’s classic “Sing Sing Sing”) and the sound of bombs exploding in wartime. Terrific! And then we see the leading character coming home from the war, vainly hoping everything will be just as it was before the war. Of course, it’s not. The country has changed. And,.more importantly, he has changed. Like I said, it’s an intriguing, unusual premise for a musical, and it piqued my interest from the start. The show has a dark, cynical tone, with unexpected twists and turns, which I appreciated.

The nationwide radio competition–hosted (the script tells us) by the famed Andre Baruch on NBC–is supposed to be honoring the vets; but it turns out to be a total rip-off, a cynical, unethical exploitation of them. We, in the audience, are expected to be rooting for the vets and angry at the greedy radio people, who–the script suggests–hadn’t known the hardships of war.

But small problems with “The Bandstand” periodically marred my pleasure, throughout the night. For example–to name one small glitch near the very beginning–it bothered me that I could not understand the very first words uttered in the show; they were simply drowned out by music. They were the only words I could not make out in the whole show. But first impressions count. Either present the words in such as way that they can be heard by everyone or eliminate them.

I liked the arc of the story, the surprising plot turns, and a goodly share of the songs. Occasionally, the story got a tad melodramatic. When one of the returning vets said that three of his friends had committed suicide to make the nightmares caused by the war go away, that struck me as dramatic overkill. The writers clearly wanted us to understand that post-traumatic stress syndrome is real. And it is But a reference to one friend killing himself to end the nightmares of war–if written well–would actually hit harder emotionally than a reference to three friends killing themselves, and would make the point more artfully and believably.

There are anachronistic lines in the show that pulled me out, temporarily, of the story. The writers, for example, have Beth Leavel’s character–who’s supposed to be a middle-aged woman in 1945–repeatedly saying “Shit happens.” That’s 1980s slang. (When people first started saying that phrase in the ‘80s, I was impressed by its novelty.) No one was saying that in earlier decades; in the 1940s, that catchphrase simply hadn’t yet been coined.. You won’t find it in any plays, films, books, or stories from the 1940s. (The “Yale Book of Quotations” says that the phrase “shit happens” first appeared in print in 1983.)

One character refers in the show to the New Amsterdam Roof–which was a famed nightspot a couple of decades before the mid-1940s setting of this show; it was ancient history–forgotten–in 1945.

The show has the swing band getting booked to play “a concert” at the Rainbow Room. That’s what one character says–a concert at the Rainbow Room. But, no! The Rainbow Room–the nation’s most elegant formal supper club–gained fame for its revolving dance floor, great view, and “name” big bands; no one watched “a concert” on that revolving dance floor. And the Rainbow Room, in 1945, was not about to book a sextet.

Perhaps the most important plot element in “The Bandstand” is that the big national radio competition turns out to be highly unethical; the competition, instead of honoring veterans as promised, is actually cheating them. The writers have this imaginary big-time radio event taking place at NBC studios in New York City, sponsored by Bayer Aspirin, and hosted by famed radio personality Andre Baruch.

I don’t know how NBC and Bayer Aspirin might like being linked, even in a work of fiction, to an unethical show that takes advantage of World War Two vets, but I’m sure the late Andre Baruch wouldn’t have liked it. Baruch–who was a very big deal in broadcasting (one of the founders of AFTRA and of Armed Service Radio)–volunteered for military service as soon as America entered World War Two. He served his country until the war was over, nearly four years later, taking part in the grueling invasion of North Africa. He attained the rank of Major, and to his dying day remained justly proud of his military service. I wish the writers of this musical had made up an imaginary radio host–or at least picked someone who had not served his country so notably well in wartime–to be the spokesperson for a supposed program ripping off the vets. Incidentally Baruch, who had been a staff announcer for CBS before the war, went to work for WMCA, not NBC–along with his wife, noted singer Bea Wain– when his military service ended in 1945.

I also didn’t buy the notion that the young vets’ combo would be booked to play (as the script stated twice in one scene) just one set lasting a mere 30 minutes. Any venue booking a live band in the mid 1940s (and paying the era’s steep entertainment tax) would want to get as much out of the musicians as possible. Patrons would want more than just 30 minutes of music, as well. There’s no need for the script to specify a “30-minute set.” That suggests a lack of familiarity with the music business, It’d be better to simply say they were booked to play that night.

The show builds to a climax with the number “Welcome Home.” I wanted to love that moment. It’s the emotional high point of the show. But for me the moment was critically weakened because the onstage band (with actors playing their own instruments) simply did not sound very good. And they were supposed to be a top band. (One member–trumpeter Joey Perro–was excellent, I should note, and he was a great asset to the show throughout. But the band’s blend was not satisfactory.) The ensemble sound on that number was unpleasant to my ears. That’s the risk you may run when you ask some actors to play their own instruments. (It did not matter in the Broadway musical “Cabaret” if some of the gals in the “Kit Kat Club” band were not great instrumentalists; they were supposed to be a second-rate band, and if their intonation was questionable, it felt right for a band in that sleazy nightclub. But this band, by contrast, was supposed to be a really good band, with a real chance at winning a national radio competition. The six-piece band Paper Mill had on stage would not have met broadcast standards for NBC in 1945.) And the actor in the band who was walking about, playing his sax with what was intended to be emotional intensity (because the song about the horrors of war meant so much to him), merely seemed to be over-acting. If you want to have actors on stage playing their own instruments for a scene like that, you need to find stronger musicians, or maybe find a way to augment them with great musicians in the pit. (The pit orchestra, by the way, was terrific. I reveled in the exit music, and the sax soloist in the pit, sailing out over the ensemble during the exit music, was a joy to hear.)

As someone who loves swing music–and liked much about “The Bandstand”–I wanted the small swing band formed by the veterans in the musical to be terrific. Most of the time it sounded rather ordinary, generic, undistinguished. If you got some better musicians, it would serve the show better. And there are arrangers who are specialists in small-band swing (from Dan Barrett and Howard Alden, to Dan Levinson); hiring one of them to craft arrangements with some distinction could help, too.

I may sound highly critical of “The Bandstand,” but the imperfections I’m mentioning are all pretty easily fixable, if the creative team chooses to make some fixes before the next production of the show. I hope they will. But none of these flaws prevented me from having a good time.

I liked the freshness of the storyline. I liked a good bit of the music. There were some scenes that were just perfect “as is” (any interaction between Osnes and Leavel was a delight to watch). Overall, it’s a pretty good first mounting of a big, ambitious show. Developing an original musical is hard. This one isn’t yet where it should be. I hope the creators can do the necessary tweaking so that the show will be in better shape, next time around. I’d like to see the show again. To me, this is a promising rough draft. And I’d like to see more from these writers.

I don’t bother writing at all about most original musicals I see (whether in full productions, festival mountings, or staged readings). Many shows simply don’t merit discussion. Or some I will cover in just a few perfunctory lines. But the writers here are trying for something good, and fresh, and big, and ambitious. Sometimes they succeed; sometimes they don’t. For my latest, there are flaws that need fixing. But I’d like to see them get this show as good as possible.

* * *

I periodically get asked by friends, “Can you recommend a show our family will enjoy?”

I’ll often recommend “Finding Neverland,” at the Lunt-Fontanne Theater on Broadway. It’s a fun show that works for all ages. Not a perfect musical. It’s not going to go down in the history books as a classic. But an entertaining, family-friendly show, with moments of real delight. If a musical like “Fiddler on the Roof” or “Carousel” or “Hello, Dolly!” rates an “A” grade, I’d give “Finding Neverland” a “B” or maybe a “B-.” The score is uneven, some of the characters feel more like stock musical-comedy characters rather than real people, and occasional lines in the script are clunky.

But–and this is far more important–the show has life and color, and surprises.

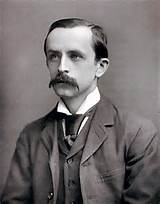

Some of the songs (like “We’re all Made of Stars”) are irresistible. At moments, the show soars. There’s much to like, for both adults and kids. It’s imperfect. But it’s better than most shows that come along. The best scenes were great fun. And I look forward to seeing it again. Is it a truthful depiction of J. M. Barrie? No! And I want to talk about that later. I must stress, I certainly don’t require musicals to be truthful, so long as they’re entertaining. And “Finding Neverland:” is highly entertaining. But I’m surprised this issue hasn’t been addressed anywhere I’ve seen. And so I want to talk about that, in a bit. But first, my appreciation for the show.

In “Finding Neverland,” the genial Matthew Morrison stars as James M. Barrie, the author and playwright who gave the world “Peter Pan.” I’ve always enjoyed Morrison’s work. (A picture I took of him and fellow cast-mates from the Broadway production of “Footloose,” about 15 years ago–at the very start of his career–is among the many photos hanging in my home.) As Barrie, he’s warm and likeable, and approachable. And seems sort of solid and trustworthy in some essential way. He makes an appealing leading man He gives us a Barrie who’s somewhat shy, a bit eccentric (in an endearing kind of way), and wonderfully generous with his gifts and with himself. A source of positive energy in the world, who helps the kids he encounters–the Llewelyn Davies boys–become all they can be.

Morrison is certainly right for the script as written. He gives a fine, thoroughly likeable performance. I don’t believe for a moment that his characterization is anything like the real James M. Barrie, but that’s another issue entirely–which I’ll get to in timey. Morrison is perfect for the ingratiating character presented to us in the script of this musical; he’s a splendid leading man; and that’s the most important thing.

The female roles are all well-cast–Laura Michelle Kelly, Carolee Carmello,. Teal Wicks are all talented pro’s who make the most of their roles. They do what they can with the rather thinly written parts they’ve been given. Playwright James Graham hasn’t fleshed out their roles very well–they don’t seem quite as real as Barrie; they’re more like stock characters, necessary for the plot.

I especially liked Laura Michelle Kelly, playing Sylvia Llewelyn Davies–the noble, doomed, widowed mother of the four Llewelyn Davies boys–but that is more due to the essential warmth and likeability projected by Laura Michelle Kelly than due to the writing or direction.

Anthony Warlow, playing producer Charles Froman, gave a commanding performance; his rich, resonant voice was a joy to hear. The script has him providing some of the inspiration for the character of “Captain Hook”–and it’s a wonderful touch, when we see his cane giving Barrie the idea for the captain’s hook. In real life, nothing of the sort ever happened, and Froman was hardly the inspiration for “Hook,” but dramatically, in the context of this musical, it works. We delight in seeing pieces fall into place, as James Barrie finds the inspiration to write the story of “Peter Pan”–the boy who never grows up–living with his band of “Lost Boys” in “Neverland.”

Jackson Demott Hill, at the performance I saw, gave a truly remarkable performance as young “Peter Llewelyn Davies”–shy, awkward, bookish, sad and lonely in early scenes, then blossoming radiantly under Barrie’s loving tutelage in later scenes. Hill was as effective as any young actor could be, in portraying the part. The script makes his character the most important of the four Llewelyn Davies boys, and a primary inspiration for the character of “Peter Pan.” That was not the case in real life–and we’ll get to that in a minute–but Jackson Demott Hill plays the part in this particular script just wonderfully.

I wish one of the songs could be transposed a bit lower for him; he has to strain a bit to hit some of the notes in “When Your Feet Don’t Touch the Ground.” and I think if the vocal part were transposed a half-step down, he might be showcased to better advantage. But he does a terrific job, overall, and contributes mightily to the show’s success.

I have a couple of good friends in the cast, with whom I’ve worked before (and hope to work again); I’m not going to comment on their work, because I can’t claim anything like objectivity towards them. I’m just happy to see them in a hit show. And am grateful that one of them gave me a deluxe backstage tour, lasting about a half-hour.

There are lots of nice touches throughout the show. And one special effect–in which glittering bits swirl about in a kind of mini-cyclone–really brought out the kid in me. A simple, but enchanting special effect.

The story we’re shown is uplifting, inspiring, positive. There is much about the musical “Finding Neverland” (book by James Graham, score by Garey Barlow and Eliot Kennedy, based on the Miramax motion picture “Finding Neverland” written by David Magee,

and the play “The Man Who Was Peter Pan,” written by Alan Knee) to admire, and appreciate, and savor. This musical, directed by Diane Paulus, gives us an idealized–and far from complete–picture of Barrie and the Llewelyn Davies family.

If the musical has a theme, it is that Barrie himself was the “boy who never grew up.” That is shown so clearly by the script and the songs and the staging, it seemed awkward and unnecessary to me to have one character in the show– young Peter Llewelyn–actually tell Barrie that Barrie is the boy who never grow up. If the production has already clearly shown us such an essential point–and it has, quite well– there is no need to also say it. I winced a little when the line was uttered; I would have preferred the playwright to have given the audience more credit than that; we’d certainly gotten the point by then, without needing to have it spelled out and underlined like that. Although Jackson Demott Hill’s joy in saying the line is infectious.

The play does a good job of showing us Barrie as being wonderfully at home with kids in general, and the Llewelyn Davies kids in particular. One of the play’s most effective scenes shows Barrie taking the kids to a stuffy dinner party; they run amok and unstarch the evening nicely. If Barrie prefers their company to that of the stuffed shirts at the dinner party, who can blame him?

In “Finding Neverland,” Barrie tells Sylvia Llewelyn Davies that she inspires him. But the line doesn’t ring true. The musical has not shown us anything to make us believe that. So that line just lays there. We’re shown the kids–not the mother– inspiring Barrie.

In “Finding Neverland,” Sylvia Llewelyn Davies is represented as a widow with four boys when she meets Barrie. Then when she dies, Barrie takes charge of her family, in keeping with her express wishes. He helps the boys, in general, to thrive. He helps Peter Llewelyn Davies, in particular, to come out of his shell. The kids inspire him to write his greatest work, “Peter Pan.” He brings out the best in the kids. The show ends on a happy, uplifting note. It is a feel-good kind of show, and such shows are always welcome. I’ve recommended it to a number of people. It’s fine family entertainment. And I want to take my youngest niece and nephew to see it next. I know they’d love it.

Is it historically accurate? Does it tell the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth about J. M. Barrie and company? No. And I don’t expect musicals to do that. I enjoyed “Finding Neverland” as a musical comedy.

But Barrie’s own life was fascinating. Someday I’d like to see his life dramatized in a more truthful way. The real story is more tragic. And more profound.

I don’t mind authors taking artistic liberties; the theater is a world of make-believe. “Finding Neverland” works, in many ways, on its own fanciful terms. It is an uplifting fable. And mass audiences always like the implication, at a show’s conclusion, that everyone will live happily ever after.

But the real story of James M. Barrie and the Llewelyn Davies family is deeper, darker, sadder, more moving.

Barrie was, in his lifetime, described as the highest-paid writer in the world. His books and plays–he had many successes, although most of his work is too sentimental for modern tastes–had extraordinary, international appeal for many years. “Peter Pan”–his masterwork–will surely live forever.

* * *

But what was the real story of J. M. Barrie and the Llewelyn Davies children like?

For one thing, there were actually five Llewelyn Davies children (not the four depicted in “Finding Neverland”): Jack, George, Peter, Michael, and Nico. When Barrie met the family, both of the children’s parents were living. The father never warmed up to Barrie, although he acknowledged that his children and his wife did. The father died of cancer. The mother–who valued Barrie as a family friend who adored her children–grew seriously ill with cancer, as well. “Finding Neverland” gives us the impression that she selected Barrie to raise her children after her passing.

But in real life, Sylvia Llewelyn Davies named a number of people, in her final writings, whom she hoped would help raise her children. She particularly specified that she hoped “Jenny”–the sister of her housekeeper, Mary, would help raise the children. In making a copy of the document for the mother of Sylvia Llewelyn Davies, Barrie changed “Jenny” to “Jimmy” (meaning James M. Barrie)–making it appear that the late Sylvia Llewelyn Davies had singled out him to work with the housekeeper to raise the children. Did Barrie deliberately, consciously misrepresent Sylvia Llewelyn Davies’ explicitly written wishes? Or did he somehow see what he wanted to see, and read “Jenny” (which she’d clearly written) as “Jimmy” (which, in cursive handwriting, looks rather similar)? We don’t know. But when Barrie wrote Sylvia’s mother that Sylvia had chosen him, assisted by the housekeeper, to help raise the children, that closed the deal. He became the surrogate father to the five children. (If he was the real “Peter Pan,” he was now raising his own brood of lost boys.)

Barrie was extraordinarily generous with them, but he could also be possessive, controlling, clingy. And he was prone to depression.

As an adult, the real-life Peter Llewelyn Davies, while acknowledging all of the good Barrie did, wrote that he felt Barrie, on balance, brought more unhappiness than happiness, into the family.

Friends of the children suggested that Barrie didn’t want the boys to grow up, and wanted to be, in effect, their “keeper for life.” The two boys whom Barrie clearly loved the most (according to the others in the family) were George and Michael. Neither grew up.

George volunteered for service when World War One broke out; he died in the trenches. (Barrie made a pilgrimage to his grave as soon as possible.)

Michael was a student at Oxford when he and another student–whose company he preferred to that of all others (as one of the other brothers put it)–died in an apparent suicide pact. They drowned in still waters, not struggling, their arms clasped around one another. Barrie was devastated, writing that Michael was pretty much his whole world. And no one was ever more important to Barrie than Michael. He and Michael wrote letters to each other daily. Years later, older brother Peter made the decision to destroy some 2,000 letters between Barrie and Michael, saying simply that they were “too much.”

In their later years, brothers Jack and Peter were no longer speaking to one another. Peter killed himself by throwing himself beneath a London subway train; he was 63. Obituaries wrote that “Peter Pan” had died. Peter Llewelyn Davies had never been able to escape his association with “Peter Pan” (which he called “that terrible masterpiece”).

The youngest son, Nico (who is not represented at all in “Finding Neverland”), remained, until his death from natural causes in 1980, Barrie’s biggest champion. He considered Barrie a great friend and great influence in his life–while also acknowledging that Barrie could, sometimes, be oppressive, and sort of omnipresent.

The real story might mot have the mass appeal of the cheerier, idealized story presented in “Finding Neverland.” But it certainly is not lacking in drama.

* * *

A few random facts concerning James Barrie and his masterwork “Peter Pan”….

Barrie developed a painful, lasting cramp in his right hand, which made it impossible for him to write any longer with his right hand. (As a writer, his hand was no more useful to him than a hook.) For the final decades of his life, he switched to writing with his left hand; he believed the writings he produced with his left hand were darker than those produced with his right hand. (And that does seem to be the case.)

The stage play “Peter Pan” was so popular in England it was mounted every Christmas from 1904 until 1939 (when World War Two ended the annual tradition). Had you gone to see the 1914 production, you would have seen a young, unknown Noel Coward (many years before he became the leading figure in British theater) playing one of the Lost Boys.

Gladys Cooper, whom many of us may recall for her work in such films as “Rebecca,” “Now, Voyager,” “Song of Bernadette,” and “My Fair Lady” (not to mention several classic “Twilight Zone” episodes), starred on stage in her youth (to great acclaim) as “Peter Pan”; she always said she felt the play was really for adults, not kids, that it contained far more than most people realized.

* * *

For many years, I’ve seen every production offered by the Westchester Broadway Theater. Their current production, “Show Boat”–running through January 31st (with some time off around the holidays)–is their best production in years. One of the best productions they’ve ever offered. Their company of 25 actors and nine musicians brings vividly to life this classic musical (which, of course, has book and lyrics by Oscar Hammerstein II, and music by Jerome Kern, and is based on the novel of the same name by Edna Ferber). I’m very glad I got to see this one. The songs, the story…. And, oh! the choreography. Very much recommended.

I don’t think any American composer has had a greater gift for melody than Jerome Kern, and “Show Boat” is Kern’s greatest score. One terrific song follows another: “Only Make Believe,” “Ol’ Man River,” “Can’t Help Lovin’ Dat Man,” “Life Upon the Wicked stage,” “You are Love,” “Why Do I Love You,” “Bill….” This production wisely restores “Mis’ry’s Coming Aroun’,” a dark number, providing appropriate foreshadowing, that was written for the original 1927 Broadway production but was cut during out-of-town tryouts. And it also includes the appealing “I Still Suits Me,” which was written for Paul Robeson to sing in the 1936 film adaptation.

“Show Boat” was such an oversized, epic musical in its original production that revivals usually make cuts here and there. This production is one of very few shows I’ve seen at Westchester Broadway that I actually wanted to last a little longer. I wouldn’t have minded spending a bit more time with the character of Julie; her sequence seemed to come and go so quickly. I wouldn’t have minded a bit more dancing. This production features some of the best dancing I’ve ever seen at Westchester Broadway. The montage in Act two, which uses changing dancing styles to convey the passage of time, was especially effective. I really delighted each time members of the company burst into dance, and would have welcomed even more.

The score really is glorious. And songs are reprised wisely, as well, sometimes with different colors and nuances the second time around. “Why Do I Love You?” works as an expression, initially, of romantic love, later as an expression of parental love. “Only Make Believe”–introduced as a duet between innocent Magnolia and the dashing gambler Ravenal–seems a conventional love song, at first. It takes on added poignance when Ravenal (who has been living in the gambler’s world of make believe, counting on the next big win that never seems to come in) tells his daughter she wil have to make believe he is there, because he’s abandoning his family.

Even before “Show Boat” opened in 1927, word had gotten around that it was a masterpiece, unlike anything previously seen on stage, and it garnered the largest advance sale of any show ever to have opened on Broadway up until then. It was more ambitious, more serious, and more unified in feel than any musical up until that time. It changed musical theater; the bar was higher for all writers of musicals after “Show Boat.”

It is not without its flaws. An awful lot happens, to an awful lot of characters, in the course of one show, and there isn’t always time for as much character development as we might desire. The storyline relies on coincidence–chance encounters of people that are much more common in musical comedies than in real life. And the happy ending feels somewhat forced. (Cap’n Andy gets to tell his son-in-law Ravenal that Ravenal–who’d gambled away family funds and then walked out on his wife and daughter–had never really been a bad guy, “just unlucky”; I’m not sure many real-life father-in-laws would have such a warm and friendly attitude.) But these are relatively minor complaints. There is so much to savor in this show, I can excuse its flaws.

This production was originally produced by Goodspeed Musicals (adapted and directed by Rob Ruggiero), and then directed and choreographed for Westchester Broadway by Richard Stafford. I consider this an ensemble success. Among the performers, I especially liked Michael James Leslie as Joe, Karen Murphy as Parthy Ann Hawks, and Jamie Ross as Cap’n Andy (although I wanted his performer to be a bit bigger, grander, more consciously theatrical, especially when he was talking to his public. Bonnie Fraser made a lovely Magnolia, and Sarah Hanlon an intriguing Julie.

It’s a great musical, and it’s good to see them do right by it.

The best production of “Show Boat” I ever saw, incidentally, was Lincoln Center’s 1966 version (at the cavernous State Theater) with an extraordinary all-star cast: Barbara Cook, David Wayne, Margaret Hamilton, William Warfield, Rosetta LeNoire, Stephen Douglass, Constance Towers. I liked the last Broadway revival (at the Gershwin Theater, in 1994), too (especially the inclusion of Elaine Stritch).

The current Westchester Broadway production doesn’t have the star power of those major revivals. But the show itself is so strong, this production is very pleasurable. And it’s nice seeing this great show in such a relatively intimate space. (The major revivals of “Show Boat” I mentioned above were in such huge venues, Westchester Broadway dinner theater feels intimate by comparison; and there isn’t a bad seat in the house.)

* * *

If I can offer a couple of brief mini-reviews. I enjoyed Goodspeed Opera House’s production of “La Cage Aux Folles” as much as just about any production I’ve ever seen there. It’s such a well-constructed show, and Harvey Fierstein’s book has so much warmth and heart, as well as humor; Jerry Herman’s score remains a treat.

The Goodspeed production felt wholly satisfying; they got just the right tone and feel. What amazed me was, they did the show with a much tinier cast and band than the original Broadway production (which still remains the standard-setter), but they managed to capture so much of the essence of the show, without ever feeling cheap. (The last Broadway revival felt cheap to me–from sets to musical accompaniment–even though I’m sure they had a much bigger budget to work with than Goodspeed. The Goodspeed production had a jewel-like perfection. The only thing that felt wrong to me was using a projection of a photo as backdrop for one scene; in an evening of theatrical make-believe, the photo seemed too literal for the rest of the show, and oddly out of place.)

* * *

I didn’t much care for “Backwards in High Heels,” an original musical about Ginger Rogers, which was presented by Westchester Broadway Theater prior to “Show Boat.” I liked the real Ginger Rogers, but this musical had somewhat of a paint-by-the-numbers feel. They told her life story in straightforward fashion (with pleasant but unexceptional performers cast as the iconic and unforgettable Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers).

To me, the night felt pretty much like…. This happened; then this happened; then this happened; then this happened; and then this happened….. I’m talking “book” problems. Presenting us with a series of facts. Not staying with any one issue long enough to make me care. Some sort of difficulty in Ginger Rogers’ life would be introduced (this man, alas, is not nice to poor Ginger) then resolved so quickly (this man is now out of her life), there wasn’t the proper buildup and release of dramatic tension that a good musical needs to have.

I was glad to see Westchester Broadway taking a chance on a new musical (rather than simply reviving a show they’ve done often over the past four decades). I like the idea of presenting new work. But, much as I wanted to love “Backwards in High Heels,” this show (and some others I’ve seen lately that I don’t even want to comment on) mostly served to remind me how hard it is to create a great musical.

* * *

“Cagney,” at the York Theater, was stronger than “Backwards in High Heels,” with better songs (by Robert Creighton and Christopher McGovern), a better star (Robert Creighton was a delight as James Cagney), and greater showmanship. But once again, book problems marred the night for me.

The show started impressively, and I was sure, in the first few scenes, I’d be giving it a rave by night’s end. But the show let me down towards the end, and I left feeling unexpectedly subdued. Some wonderful moments in the show (I liked the song “Black and White,” and the very human overall portrait of Cagney). The audience clearly loved the show. And I wanted to love it. (Cagney remains my all-time favorite screen actor, and the autograph he gave me is a prized memento in my office.)

Robert Creighton captured a good bit of the real Cagney we all know and love, and for that I’m grateful. But for me the show lost some steam in the second act. And I didn’t care for either the over-emphasis on Bob Hope in the show or the actor who was cast–but simply couldn’t satisfactorily fill the shoes–as the one-and-only Bob Hope.

* * *

When my schedule permits, I like to see shows at colleges and conservatories in the region: NYU, Juilliard, Wagner, Princeton, etc. Over the years, I’ve seen in such shows–and have written up–promising students who’ve since gone on to Broadway success. It’s always fun to see what the colleges and conservatories are up to. I’m very glad I made it out to Hofstra University to see their production of “Fiddler on the Roof,” directed by Cindy Rosenthal (whose fine Hofstra production of “Rent,” about four years ago, I covered at the time in this column).

“Fiddler on the Roof” is a challenging musical for anyone–much less college students. It is one of the all-time great musicals, an extraordinary achievement in the art form. The original production, in the 1960s, became the longest-running musical in Broadway history, up until that point. I have seen many productions of this show over the years–not just on Broadway, but also the last national touring company, and productions mounted by the Goodspeed Opera House, Westchester Broadway Theater, and the Bucks County Playhouse.

This Hofstra student production benefitted from having three pro’s guide it: director Cindy Rosenthal, choreographer Stas Kmiec, and music director Andrew Abrams–all of whom are veterans of past productions of “Fiddler” starring the late, great Theodore Bikel (to whom this production, running through November 1st, is dedicated). They know the show well, and they have done justice to it. The staging is based upon the brilliant work of Jerome Robbins, who directed and choreographed the original 1964 Broadway production.

I went to Hofstra’s spacious John Adams Playhouse hoping for an enjoyable student production. What I witnessed was much more than that–for this was the most rewarding college theatrical presentation I’ve seen anywhere in a couple of years. The production values–as is usually the case for big Hofstra shows, whether the shows themselves are otherwise successful or not–were first rate. The huge cast delivered solid ensemble work.

The star, Michael Caizzi, a junior at the university from Barrington, Rhode Island, was a revelation. He commanded the stage from the moment he entered. It is extremely rare to find that sort of ownership of a stage in a college student. It is rare, for that matter, to find it in performers of any age. (When, for example, I saw Eddie Mekka, from the sitcom “Laverne and Shirley,” star as Tevye in “Fiddler on the Roof” at Bucks County Playhouse, he certainly didn’t have it; his performance was pleasant, very-much-on-the-surface, and forgettable.) Caizzi, as Tevye, had terrific stage presence. And a terrific feel for the character: big when he needed to be big (“If I Were a Rich Man,” with appropriately ethnic delivery of the lyrics), and yet wisely quiet, small, vulnerable when the moment required that choice for maximum effect (a tender “Do You Love Me?”). I liked the comic timing he displayed when relating to his wife then improbable dream he claimed to have–even down to the offhand way he flicked a pillow into place to muffle the sound of a cymbal player (Noah Smith). And I enjoyed the ways he’d react the character of the Fiddler–perhaps shooing the Fiddler off the stage with a gesture that had a welcome touch of the clown in it. I doubt I’ll ever see a better performance by a college student as Tevye.

I would love to see Caizzi play this role again 10 years from now, and again 20 years for now, because it is an extraordinarily rich role and he will find even more in it with more life experience; Zero Mostel was able–by subtly varying the Jewish inflection he’d bring to lines–to let us sense Tevye’s mixed joys, pains, frustrations. It was a tragedy that Mostel–a theatrical giant, in the role of a lifetime–did not get to star in the film version of “Fiddler on the Roof,” and that the part went to a performer (Topol) who was, when he made the film, much more conventional and one-dimensional. (I got to see Topol do the same part better, years later, at the New Jersey Performing Arts Center; seasoned by time–he delivered a much more satisfying performance than he’d delivered on screen.)

I liked Caizzi’s work when I first saw him at Hofstra when he was a freshman two years ago; the potential was there. And I like samples of his work I’ve seen online But one of the reasons it can be so exciting to watch performers early in their careers is that, when they’re young, they are capable of growing tremendously in just a year or two. And he’s grown tremendously since I first saw him. I was not prepared for just how rewarding Caizzi’s performance would be. It’s one of the most enjoyable performances I‘ve seen anywhere of late. A most welcome surprise. And I’m looking forward to seeing what he’ll do next.

Attending college shows is a hit-or-miss thing. And colleges don’t always have, in their classes, performers of this strength. (When I saw “Gypsy” at Hofstra, two or three years ago, the thing didn’t work because they did not have a star capable carrying off the challenging main role with even a fraction of the needed brass.) The last time I saw a performer at Hofstra who really knocked me out was a couple of years, watching Anna Holmes play the title role in a near-perfect little production of “The Drowsy Chaperone.” After seeing the show, I told my longtime friend Lisa Lambert, coauthor of “The Drowsy Chaperone,” that young college-student Holmes, who was then brand new to me, was stronger than the professional actress they had playing the role in the national tour, and that I hoped I could work with Holmes, in some way, someday. I feel that was about Caizzi; he was fearless on stage–in a part that would and should strike fear into the heart of most aspiring performers.)

After Caizzi, the performance that most impressed me–another wonderful surprise–was that of Peter Charney, whose energy, passion, and total commitment, playing Perchik (a student and revolutionary) captured me throughout. The director had him enter from the back of the house–a nice touch, since he’s an outsider, not from the village of Anatevka, Russia–and even before he uttered a word, his body language and bristling energy told us exactly who the character was. I’m certainly familiar with Charney’s acting–and he’s acted for me on stage in past years–but so much time had passed since I’d last seen him in a musical, it was startling to observe his growth as a musical-theater performer. Like Caizzi, he put everything he had into the performance. And I enjoyed the true, earnest rendition of “Now I Have Everything,” sung by Charney and the well-matched Caroline McFee, playing Tevye’s daughter, Hodel. The other main daughters, Tzeitel (Sabrina Sutton) and Chava (Anna Watts) were played effectively as well, with good chemistry between them and their future spouses (played by Daniel Artuso and William Ketter–I wish I could have seen more of Ketter, who was wholly winning in his small role). And Sheila Springer was satisfying as Golde, Tevye’s wife.

The direction of the show, and the choreography, and the performance of the orchestra were highly commendable, and I was moved to tears a couple of times. The set design was first-rate, and I want to remember the name of the designer, Nic Christopher, who just graduated from Hofstra last year. I’m sure we’ll see more from him.

Among the dancers, Noah Smith was the standout. No matter how he was disguised–whether as a Russian dancer or as a Jewish dancer, or playing any small ensemble part–he had presence and demanded your attention. I’ve noted his stage presence in the past as well (even one time when he was pulled up from the audience, randomly, in a performance of “The Puppet Show Man” at Dixon Place). A good director can spot presence in an instant, on first meeting.

As a director, I advise any performers I work with to respect, and build upon, whatever strengths you happen to have been blessed with. If you have some stage presence, that’s a gift to take seriously–and build upon–because it can’t be taught in school. You can learn technical skills; you can learn skills of singing and acting. If Noah Smith were in my pool of available actors, I’d make more use of him, because presence is invaluable. Some Broadway theater-goers “discovered” Cody Green when he starred as Riff in the last Broadway revival of “West Side Story.” But I saw that same presence when he was a dance student at Juilliard, back in 2000. He thought of himself as a pure dancer then–he had not yet taken lessons in singing and acting, but I’m glad he decided to explore his potential in those areas. Because he already had presence. He was the standout dancer in his class at Juilliard. And he built upon that foundation to achieve all-around success as a performer. If an opportunity arose, I’d use Caizzi or Charney or Smith on a project in a heartbeat. (Just as I would Anna Holmes, who dazzled me so much at Hofstra a couple of years ago, or Hofstra-senior Jack Saleeby, if they were interested.) They’ve got something.

I liked this production of “Fiddler” a lot. And the balance between the singers and the orchestra was just perfect. At the best moments, I felt almost like I was in a Broadway theater.

The one scene that didn’t have as much impact as it should have was the final scene of Act One, when a wedding is interrupted by violent Russian soldiers, whose actions foreshadow the pogrom to come. This scene should hit home with great power, but its impact was muted. We saw Russian soldiers moving about somewhat randomly.. We eventually heard offstage yells and shouts and screams, which were supposed to be Jewish villagers suffering at the hands of rampaging Russians but sounded, alas, more like college actors yelling/shouting/screaming on cue. The scene didn’t quite ring true. It didn’t land with the horrifying impact it should have.

I’ve seen a lot of different directors put their own particular stamps on “Fiddler on the Roof.” In the most effective presentation of the Russian violence I’ve ever seen, the director–through staging and lighting–focused our attention on one Russian soldier who grabbed a pillow that had just been given to the bride and groom as a wedding present, and slashed it with his knife, releasing a startling spray of feathers into the air. That one seemingly small gesture–the start of the violence–said so much. We knew we were seeing the destruction of more than one pillow from a couple’s marriage bed–their future happiness, as a married couple, was being robbed from them; and we understood that the violence beginning would rob everyone in the village of future happiness. The one small act–slashing the pillow–felt so disrespectful, so violational, it communicated the horror of pogroms to come more than random movements and yelling and shouting could

“Fiddler on the Roof” is an unusually powerful, rewarding, and important musical. Its creators–composer Jerry Bock and Sheldon Harnick, book-writer Joseph Stein, original director/choreographer Jerome Robbins, original producer Harold Prince–brought us a masterwork. I never tire of the show. And it reveals more to me each time I see a production. The score, by Bock & Harnick, is extraordinary: one terrific–and richly human–number following another: “Tradition,” “Matchmaker, Matchmaker,” “If I were a Rich Man,” “To Life,” “Tevye’s Dream,” “Sunrise, Sunset,” “Anatevka…..” The show has so much heart. Great book scenes give way to even greater musical numbers.

* * *

I always admired Bock & Harnick’s work. They were a great favorite of mine, among Broadway songwriting teams. There are rewards aplenty to be found in such other shows of theirs as “Fiorello,” “She Loves Me” (a sublime score), “The Apple Tree” (which charmed me when it first opened on Broadway, although it is a smaller kind of show than the others). I wore out my cast album of “To Broadway with Love” (which included songs by Bock & Harnick, along with vintage numbers), when it was released in the ‘60s; I can still sing the catchy title song (which they wrote) from that show

I just loved Bock & Harnick’s work. In their all-too-brief period of partnership (just 12 years), they seemed well on their way to becoming one of the legendary, great, permanent partnerships in Broadway history. But they decided, while working on “The Rothschilds”–the story of the famed European banking dynasty– to end their partnership. And that professional “divorce” took. They never did another show again.

I wish they had done more. I wish they’d ended their professional partnership with something stronger than “The Rothschilds.” The show, which opened on Broadway in 1970, was quite a let-down, compared to “Fiddler on the Roof.”

Well, the very same weekend that I caught “Fiddler on the Roof” at Hofstra, I caught “Rothschild & Sons”–a reworking of “The Rothschilds”–at the York Theater in New York City. And, alas, it still remains a tremendous let-down compared to “Fiddler.” Don’t get me wrong; there are some significant rewards to be found in this production, and it’s worth seeing. But don’t go expecting to see anything nearly as memorable as “Fiddler.” I enjoyed far more this college production of “Fiddler”–it’s as perfect a musical as you can hope to find–than I did the new reworking of “The Rothschilds.”

* * *

Composer Jerry Bock died in 2010. But Sheldon Harnick, who wrote the lyrics for “The Rothschilds,” and Sherman Yellen, who wrote the book,. are still with us, fortunately, and they have reworked/re-imagined “The Rothschilds”–which was a big, full-scale Broadway musical–to create “Rothschild & Sons”–a much more intimate show, written for a cast of 11.

I wish I could rave about this new production (directed by Jeffrey B. Moss), because its heart is certainly in the right place. And they’ve got a magnificent star, Robert Cuccioli, giving the best performance I’ve seen in his career. (And in the past 25 years, I’ve seen him starring or co-starring in plenty of shows, from “Jekyll and Hyde” to “Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark”).

This musical play is uplifting. The tale it tells is worth telling. And it is a moral show. There’s much to admire about the script. (And I particularly like the way the show presents one key scene twice–to open the piece, and then again in context.)

The chief problem with the show remains the score. In a great musical like “Fiddler,” rewarding book scenes lead in to even more rewarding musical numbers, and the emotional impact of the show grows. In “Rothschild & Sons,” rewarding book scenes all-too-often seem to lead into less-interesting musical numbers. And it’s hard to love a musical, no matter how uplifting the narrative is, if most of the musical numbers don’t do much for you.

The score is not as catchy, nor as richly melodic, nor as appealingly varied as are Bock & Harnick’s wonderful scores for “Fiorello,” “The Apple Tree,” “She Loves Me,” or “Fiddler.” The score for this show, all too often, feels weak, watery. It seems, at times, to be a faint echo of “Fiddler.” The performers–solid professionals all–do as much as possible with what they’re working with. But the weakest songs feel like pretty much like “filler” to me. It is hard to believe this score is by the same team that gave us “Fiorello,” “The Apple Tree,” “She Loves Me,” or “Fiddler.” Interestingly, Bock and Harnick said “no” the first time a producer approached them about the possibility of doing a musical about the Rothschild banking dynasty. Perhaps they should have trusted their initial instinct. It doesn’t feel like their heart was in it, when they crafted this score.

But the score is not quite the only problem with the show.

The story–about a Jewish father raising his five sons to prosper and thrive as bankers (despite oppression) and successfully fight anti-semitic rulers–is interesting, but it does not touch us as deeply as the stories told in “Fiddler” do. It is a serious story, seriously told. The Rothschilds’ fight to make the most of themselves and to secure equal rights for Jews is noble. And I like Serman Yellen’s writing; I long have. Watching this musical play, of course we want the Rothschilds to succeed. But it is also a more obvious kind of story, without as many layers or nuances as are to be found in “Fiddler” (which of course was based on the great stories of Sholem Aleichem). It doesn’t feel as big or as universal. And we don’t connect as completely or as emotionally with this family as we did with the family at the heart of “Fiddler.” The hard-pressed Tevye and his five daughters (wondering who they’ll marry, trying their best to cope with a changing world) reach our hearts more than Mayer Rothstein and his five prospering banker sons.

Cuccioli’s performance is first-rate. He’s never been in better voice. And the script gives him opportunities to remind us–in ways not all of the musicals he’s done in New York and at New Jersey’s Paper Mill Playhouse over the past 25 years have–what a fine, warn, sensitive, and subtle actor he can be. He gives a tremendous performance–winning and utterly convincing.

Cuccioli really was inspired casting. (And he certainly knows the show and subject matter well. A quarter-century ago, Cuccioli played one of the sons, Nathan, in an Off-Broadway production of “The Rothschilds!”) He’s such a vital part of this show that my interest in the show fell off a good bit when his character died; boy, I missed him when he was gone, and almost wish they could have kept his character around longer (although he’s already around longer, if we’re talking history, than the real Mayer Rothstein was–not that I require musicals to be as accurate as history books). But I sure felt his absence when he died.

I relished every bit of the deliciously evil characterizations that Mark Pinter came up with, playing the various heavies in the script. What a wonderfully regal, eccentric and loathsome bad guy he makes! It really is a treat to see him on stage. I have no idea if the real Prince Metternich was anything like the characterization Pinter gives us, but Pinter’s portrayal is unforgettable.

I may complain about the blandness of much of the score, but if you’re thinking of buying tix to “Rothschild & Sons,” let me assure you that you will get your money’s worth just from the top-drawer performances of Cuccioli and Pinter.

Mark Pinter has appeared often on TV throughout his career, with long runs as a contract player on various daytime dramas, including “Love of Life,” “Guiding Light,” “as the World Turns,” “Loving,” “All My Children.” For his portrayal of the dishonest politician Grant Harrison on “Another World” (1991–99), he won the Soap Opera Digest Award for Best Villain.

Rounding out the cast (and often doubling in roles) are: Glory Crampton, Jamie LaVerdiere, Peter Cormican, Jonathan Hadley, David Bryant Johnson, Christine LaDuca, Nicholas Mongiardo-Cooper, Curtis Wiley and Christopher M. Williams.

The audience in the jam-packed theater appeared to enjoy “Rothschild & Sons” more than I did. A cast album is being recorded. This more compact retelling of the story of the Rothschilds–only 11 actors, just one act–may have appeal for regional theaters. The story is told quite effectively by just 11 players. This is not a musical that needs a big singing/dancing chorus.

The only significant loss in re-imagining “The Rothschilds” for this smaller cast is that we no longer get to see the sons first as children (played by young actors in early scenes of “The Rothschilds”) who mature into men (played by older actors in subsequent scenes); in “Rothschild & Sons,” the sons are played by older actors throughout. (A young, not-yet-famous Robby Benson played one of the youthful Rothschild sons in the original Broadway cast!) The original Broadway production of “The Rothschilds” handled the changeover from children to men quite brilliantly; the children went into the basement of their home, in hiding from anti-Jewish persecution, in one scene; when they emerged from hiding, they were men; the point was made vividly that the persecution had gone on, year after year.

* * *

Sometimes, I just have to count my blessings. I’m very grateful for the life I have. Jon Peterson has been performing my one-man show “George M. Cohan Tonight!,” off-and-on, for more than a decade. As I type these words, he’s just finished doing my show in the Fringe Festival in North Hollywood. And tonight, the show won the NOHO Fringe Festival award for “Best One-Person Show.” No one writes a show to win awards–but it’s always nice when a performer and a show gets that kind of recognition. And Jon and the show have received a number of awards over the past decade. It’s funny; I wrote that show (and other shows about Cohan) quickly, as a labor of love, not knowing–or caring–if anyone else would be interested.

I always simply do the projects I want to do, without worrying about the financial rewards that may or may not ever come. (That approach may not sound practical, but it is fulfilling.) My father raised me to believe: “Do what you love; the money will find you.”) I wrote “George M. Cohan Tonight!” because Cohan’s been a lifelong idol of mine. And–although that show has been performed by a number of actors since then–I wrote it specifically for Jon Peterson, tailored to strengths I saw in him the from the moment we met. And he keeps bringing more to it, keeps surprising me. . I hope he keeps performing the show for many years to come. (I’d like to take the show back to Korea again, and back to England again.) Jon is as good as the get. Any playwright would be grateful to have his work performed by so conscientious and talented an artist.

* * *

Sometimes—it’s very rare but quite real—you know the moment you meet someone that they’re a huge talent. I knew that the minute I met Jon Peterson. And I knew it the minute I met young Giuseppe Bausilio. (He was just 16 at the time.) I was very grateful to have him co-star (with Michael Townsend Wright) in the New York premiere of my show “Irving Berlin’s America.” I felt then—and feel now—he’s a major talent, with a great future ahead of him. I’m very happy for Giuseppe–and not the least bit surprised—that he’s been cast in a leading role (“Alfie”) on a TV series (“The Next Step”) on The Family Chanel. The sky’s the limit for this young man.

* * *

Right now I’m celebrating the release of the cast album of my show “The Irving Berlin Ragtime Revue.” It’s always a joyous occasion to have another cast album come out. (This is my twelfth!) This one was particularly complicated to record because we have 13 performers doing a whopping 44 musical numbers. But I always enjoy making albums, and feel particularly happy about this one.

Recording the cast album allowed me spend a bit more time with a hand-picked company of artists that I really love: Emily Bordonaro, Keith Anderson, Michael Kasper, Rayna Hirt, Jonah Barricklo, Michael Czyz, Missy Dreier, Timothy Thompson, Carolyn Montgomery-Forant, Ann-Marie Calabro, Andrew Lanctot, Maite Uzal, Richard Danley. No one ever did a show before celebrating Berlin’s Ragtime Era songs. And I’m happy that we got to include many songs that had not been recorded in a century–and some that had not been recorded at all.

The “Ragtime Revue” is one of five different shows about Berlin that I’m developing. And this album is the third album–of eight planned–that I’m producing, celebrating the legacy of Berlin. (The next should be out by year’s end.) Berlin was the single most successful songwriter in history; he wrote more hits and made more money than any of his competitors. He was–along with the Gershwins, Cole Porter, Jerome Kern, and a couple of others–one of the all-time greatest of songwriters. He wrote some 1500 songs–and there are quite a few forgotten gems in his catalog. I’m doing my best to help bring them to light.

– CHIP DEFFAA, October 31st 2015

Leave a comment