REMEMBERING GIL WIEST—THE LAST OF THE GREAT CABARET SHOWMEN—AND MICHAEL’S PUB

Whether performers liked him or disliked him, they agreed that Gil Wiest—the last of the great nightclub impresarios—kept them working. He routinely booked artists for long runs—a month, or six weeks, or two months. For decades he made his supper club, Michael’s Pub, a prime destination for top-tier cabaret and jazz.

By CHIP DEFFAA

I’m sorry to note the passing of Gil Wiest, who long ran one of the greatest of New York nightspots, “Michael’s Pub.” He had such a wonderful impact on New York nightlife, I want to just take a moment to remember him.

He had terrific taste in talent, and terrific instincts for how to sustain a booking. He was the last of the great cabaret impresarios. He was a stern, demanding, perfectionistic sort of man. He maintained exacting control of everything at his venues. And he had high standards. I liked him. Not everybody did. He told me that it was not his job to get everyone to like him; it was his job to keep his club going, and to keep presenting artists he appreciated. Whether performers liked him or disliked him, they wanted to play his room. And when he retired at age 77 in 2002, he left a void on New York’s entertainment scene that no one else filled.

Gilbert Wiest was born June 5th 1925. After service in World War Two, he worked in the garment business before moving into the restaurant business. (He once told me that you had to be tough to work in the garment business in New York, and that gave him good preparation for his career as a restauranteur and cabaret showman.) He established himself as a restauranteur in the mid-1950s. From 1975 until 2002 when he retired and moved to Southern California, he was a major player in New York nightlife . For about a quarter-century, his “Michael’s Pub” was one of New York’s top supper clubs.

Gilbert Wiest was born June 5th 1925. After service in World War Two, he worked in the garment business before moving into the restaurant business. (He once told me that you had to be tough to work in the garment business in New York, and that gave him good preparation for his career as a restauranteur and cabaret showman.) He established himself as a restauranteur in the mid-1950s. From 1975 until 2002 when he retired and moved to Southern California, he was a major player in New York nightlife . For about a quarter-century, his “Michael’s Pub” was one of New York’s top supper clubs.He booked artists for much longer runs than anyone else in the city, then or now. I remember when he presented Julie Wilson saluting Cole Porter for two-and-a-half months. He believed in long runs. Long runs meant more press coverage, he noted, and they gave everyone time for word of mouth to build. He had a team of top publicists working for him—Henry Luhrman, Terry Lilly, David Gersten—and they could get interviews, not just reviews, in the press, for artists the club presented.

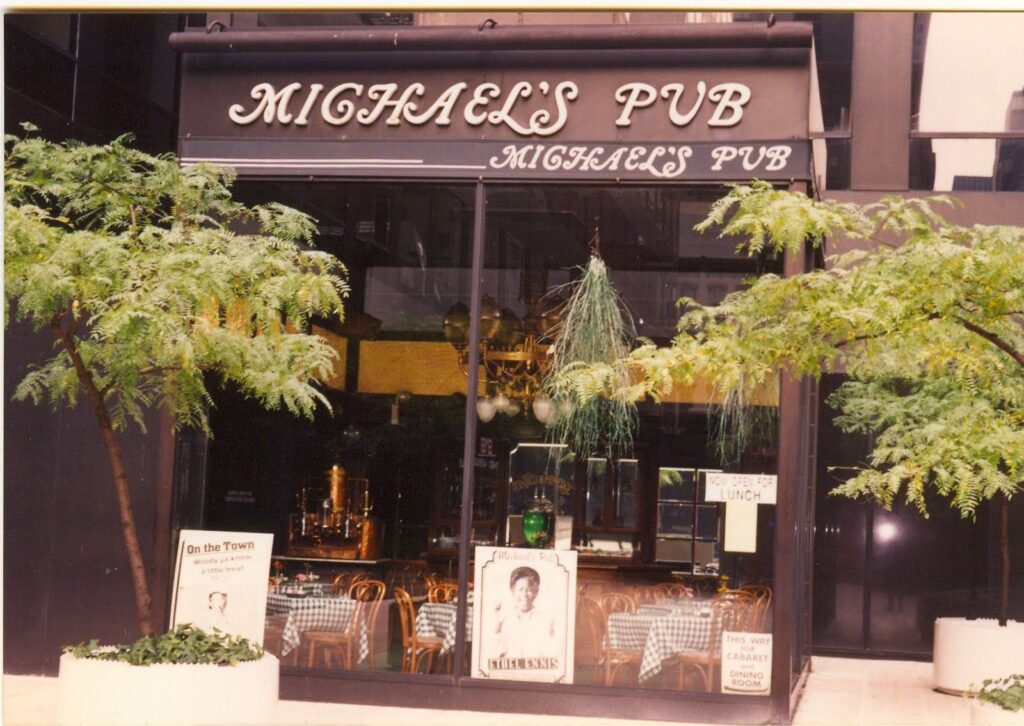

And what artists he presented! He impeccably showcased Mel Torme, Anita O’Day, Ruth Brown, Barbara Cook, Vernel Bagneris, Sid Caesar and Imogene Coca, Sylvia Sims, Vic Damone, Joan Rivers, Margaret Whiting, Kay Ballard, Rosemary Clooney, Benny Carter, George Shearing, Hank Jones, Joe Venuti, Stan Freeman, LaVern Baker, Hadda Brooks, John Pizzarelli, Ethel Ennis, and countless other notable artists. He didn’t just book artists, he critiqued their performances. And he did not pull punches.

He presented filmmaker Woody Allen’s Jazz Band every Monday night–with no advertising, never a mention of Allen’s name to the press. (The band was originally billed as the New Orleans Funeral and Ragtime Band, or some such thing.) Woody’s band (without Woody being billed) drew packed houses for 25 years due to word-of-mouth. And helped make Michael’s Pub, at 211 E. 55h Street, the place to be. (When Wiest retired, Allen’s band found a new home for the next quarter-century at the Café Carlyle.)

Wiest liked Woody Allen and Allen’s New Orleans-style jazz, although Wiest often maintained an expressionless poker face so you weren’t sure where you stood with him.

Wiest told me a curious little story once that I think gives a little insight into the way Wiest operated. When Wiest invited Allen to play a little jazz for a few Monday nights, just for fun, neither had any idea it was about to become a permanent gig. Allen and his musicians rehearsed a bit, off-site, in preparation for their appearance at Michael’s Pub. One of the musicians casually mentioned to Wiest, as their Michael’s Pub debut was approaching, that Allen—who was used to operating on his own terms–would play a single hour-long set, and that would be it; he would not play encores, or even a minute longer than the specified one hour.

Wiest told me: “When Woody arrived at the club, I told him in no uncertain terms, before he had a chance to say anything: ‘We’re trying you out tonight. You may play for one hour and not a minute longer. I don’t believe in encores. I won’t permit you to give encores. Don’t milk the applause. When you’re done, you’re done.’ That night, Woody gave three encores, just to spite me, just to show me who was the boss. And of course, the audience loved those encores; they felt they were getting a bonus. I told Woody I was angry at him for defying me…. And by doing that, I’ve gotten him to give three encores every set, ever since then.” Smart cookie!

Wiest would tell members of the press (including me): “We don’t want anything in the press about Woody playing here. He wants his appearances her to be under-the-radar. Nice and quiet. We don’t want this club turning into some kind of a tourist attraction.” Which of course generated more publicity, and helped create a mystique about Michael’s Pub and Woody’s gig there. Again, Wiest knew what he was doing. And Allen came to feel Michael’s Pub was like a second home to him. He was there virtually every Monday—even choosing not to attend the Oscars one year, preferring to stay in NYC and play his regular Monday-night gig.

Wiest did first-rate salutes to songwriters he appreciated , from Jelly Roll Morton to Sondheim. And he didn’t just book existing acts, he conceived shows and commissioned artists to bring his concepts to life.

Only one songwriter objected to Wiest presenting a salute to him: Irving Berlin. When Berlin read a piece that I wrote in the New York Post saying Michael’s Pub was going to salute Berlin, Berlin objected. Gil phoned me, saying Berlin had read my article and was threatening legal action. Gil Wiest was one tough cookie, but he was not about to fight Irving Berlin. He reluctantly agreed to cancel that Berlin tribute show. (I’ve worked this incident into a couple of plays I’ve written.)

But that was not quite the end of the story. Wiest–who did not give up easily—then opened a “new” show that was no longer billed as a salute to Berlin, and consisted of 75% Berlin songs, instead of 100% Berlin songs. So, I’m not sure who “won” that particular battle.

Wiest told me he survived for all of those years because he had the toughness needed to run a New York nightspot, and because he had the good taste to know who to book and how to present him. He trusted his instincts 100%, booking artists he liked. (The only time his instincts failed him, he once suggested, was when he booked Mickey Rooney for a month. In Wiest’s youth, Rooney was a box-office king, and Wiest was proud to showcase him. But audiences simply did not turn out; Rooney’s time had passed.)

Wiest liked big bands and presented singers like Mel Torme and Anita O’Day in big-band settings no other clubs would dream of offering. It cost him a more to present singers he liked with big bands rather than small groups, he noted, but he was willing to gamble that a greater show would be a greater draw in the long run. And it was thrill to see Anita O’Day with “the Gene Krupa Orchestra,” re-creating her big band era hits. It was an event.

Musicians who played Michael’s Pub shared with me recollections of Wiest and his club.

Trumpeter Russ Konikoff noted: “I played a few one-month gigs there with Mel Torme in the late 80s with a full big band. Mel killed it every night! We had a wonderful month every time, but we were warned not to speak to Gil for any reason, not to bother him about anything, to just stay away. Then one night, one of our sax players walked in before the show, threw his arm around Gil’s shoulder, as though he was Gil’s old buddy, and asked about comping one of his friends for the show. Gil pulled away, and a moment later a man the size of Luca Brasi picked him up and threw him out the front door. I was the band contractor, and when I heard, I ran to Mel, and Mel had to do some fancy talking to get him back in to play the show!”

Saxophonist Loren Schoenberg recalled: “I led bands for Gil, and also was there as a sideman for a few engagements–the one with Harold Nicholas doing Astaire was wonderful, as was another one with Sylvia Sims with Buddy Barnes on piano. And for all his oddnesses, Gil had a VERY good ear. I brought in a big band to back Frank Stallone, who had a book of new charts by Billy May– and one night there were a few subs in the band. When we came off the bandstand, Gil had heard precisely which one of them had miss-stepped–that’s a good ear!”

Alan Eichler, who booked many artists he managed into Michael’s Pub, reflected: “Gil could be saint or monster. He had impeccable taste in music and if he liked you, he could be the nicest man alive. But if he disliked someone, he was a total sadist; I saw him be cruel to many people. But there’ll never be anyone like him. He was the last of the cabaret showman. Among acts I had there: Ruth Brown, Anita O’Day. Chris Connor, Marilyn Maye (where her current resurgence actually started), Spider Saloff and Ricky Ritzel, Nellie Lutcher, Ella Mae Morse (who he cruelly fired), Hadda Brooks, Thelma Carpenter, and more. He cancelled LaVern Baker when she asked for an extra week to recover from having her two legs amputated!”

Maryann Lopinto commented: “His taste was great, but he was a tyrant.”

Noted tenor saxist Scott Hamilton recalled: “I worked for Gil my first extended NY gig in 1976. And again, in the 90s. I was always a little scared of him– you never knew if he liked you or not. Once in a while he let the mask slip and smiled. Michael’s was a unique club in the 70s – they had guys you wouldn’t see in the Village and they ran for six weeks at a time: Zoot [Sims], Benny Carter, [Joe] Venuti, Flip [Phillips], Earl Hines, Hank Jones, Red Norvo….”

Trombonist Dan Barrett recalled: “I performed at Michael’s Pub several times while I lived in NYC, including several nights with the quintet I co-led with guitarist Howard Alden. It always unnerved me to suddenly notice Gil lurking in a dark corner of the place–Bela Lugosi comes to mind. Bassist Michael Moore told us a funny story about an exchange between Gil and Ruby Braff one night…It was a minor verbal confrontation, and… Ruby won.”

Loren Schoenberg remembered: “When you came off the bandstand and out of the main room, Gil would be standing there with his glasses halfway down his nose, ready to give you his review of the set–which was not always a good one. Benny Carter told me the way to get around it: look towards the door at the front and say ‘Is that Ella coming in?’ as a diversion to escape.” Schoenberg acknowledged that Gil had great taste and gave a lot of people work. But also recalled that Wiest could be very tough on people: “He kicked Joe Williams out one night, which is hard to imagine as Joe was such a sweet guy. . That reminds me of the old joke about two old women who ran into each other. One them admires the other’s ring: ‘What a beautiful ring!’ ‘Thank you, but it came with the Tishman curse.’ ‘What’s that?’ ‘Mr. Tishman!’”

I saw Gil Wiest being gruff and demanding with artists he employed—once even chewing out a great singer because she had dared to perform a set at his club with a Band-Aid on one finger. (He considered that to be un-glamorous—an unacceptable imperfection, a distraction.) I once saw him critique the job being done by a bus boy. When I asked the bus boy if it bothered him be criticized like that, he said something like, “Mr. Wiest wants things just so. It’s all right. He’s paying attention to me. I don’t think the boss at the last place I worked would ever have even spoken to a bus boy.”

Anita O’Day told me she found Gil intimidating, and asked if I could intercede on her behalf in some dispute over money she was having with him. I wasn’t about to get involved. But it fascinated me that Anita O’Day–who had lots street smarts and lots of Moxie, and projected a certain toughness of her own–found Gil intimidating.

If he wasn’t satisfied with the way an act was going, Wiest might end their set prematurely—cutting off their mikes, and bringing down the lights to signal they were done whether they liked it or not. And they wondered—not unreasonably—if they were going to get their agreed-upon pay. Bill Daugherty was one singer who told me he took Wiest to court to get paid what he was due. Daugherty couldn’t forgive Wiest for that.

Drummer Frank Derrick commented: “There was another side to Gil that most people did not know. One time I was on a run at Michael’s Pub with Arvell Shaw. I had hurt my back so bad moving drums that I could barely walk. He would not let any of the musicians help me as he would lock arms with me & walk me to & from the stage for each set, and getting seated behind the drums. I thanked him afterwards and he winked at me saying, ‘Let’s keep this between us. I’d hate for this to get out.’ I’ll never forget. RIP Gil Wiest.”

Greg Dunmore offered condolences and “fond remembrances of a memorable man.” He shared these thoughts: “My mother, pianist and singer Jo Thompson, was booked at Michael’s Pub for seven weeks and I have LOTS of colorful Gil Wiest moments–some good and others… well… you already know (smiles!!!)…. Nevertheless, I learned a lot from Gil who put Michael’s Pub on the map as a destination. I remember he asked me one day had I heard about his “reputation”–which I honestly had not (especially as a young Black man from Detroit). When I told him, I hadn’t heard anything about him, he said– with a Cheshire Cat smile and a wink: ,”That’s a good thing, but you will.” And of course, I did!”

I liked Gil Wiest, and sensed the warmth under the tough guy veneer. He’d never say, “It’s good to see you, Chip.” He’d say something like, “You’re back again? I don’t want anyone making this place their hangout.” And then get me a good table. And tell me he liked my parents. Which was as close to a direct compliment as he could get. He introduced me to his good friend, Joan Benny—Jack Benny’s daughter. I enjoyed meeting her.

Gil could often be tough on people he worked with. But he gave them long runs and publicized them well. He knew how to turn a booking into a must-see event. No one’s doing that anymore. And by offering long contracts, he could make it worthwhile for artists from any part of the country to come and play his club, and develop whole new shows.

Pianist Alex Rybeck remembered Gil Wiest and Michael’s Pub as “an essential piece of the nightlife of the city for many years…. I’m so glad you brought up the topic of long bookings. This is my biggest beef with today’s cabaret scene. Why did this policy of booking the best acts for long residencies change? Now, almost no one–no matter their name, reputation, drawing power–can secure more than a night or two, and that’s killing the art form. How are artists supposed to build their audiences? How does it make sense to spend months creating a new show only to do it for one night only? How does the show achieve its potential? What is the point of a rave review if there are no additional shows for the readers of the review to go to? I have to assume that club owners thought that having a different act every night would make them more money than featuring longer runs of popular cabaret stars. If that’s so, please tell me which cabaret room is presently rolling in dough? I fervently hope the old policy of booking long(er) runs returns to the scene. It was so much better for performers and audiences and the press; and I suspect, for the clubs, too.”‘

Some good albums (including a couple of Mel Torme’s) were recorded “live” at Michael’s Pub. Gil recorded many of the shows he presented, if only to have reference recordings for his personal archives. His estate is now in possession of about a hundred tape-recordings of shows he presented at Michael’s Pub. I hope they find a good home; there’s lots of musical history there.

Gil Wiest passed away on October 31st in Santa Monica, California. He was 99. My condolences to his sons and to his grandson, Henry Wiest, who first informed me of his passing.

Leave a comment