On the Town with Chip Deffaa: “Rent” at the Frank Sinatra School of the Arts: An Appreciation

I don’t write about most high-school or college productions I see. But once in a while I will see a student production somewhere that is so satisfying—and so unusually impressive for a student production—that I need to write something. And these students sure came together as an ensemble beautifully.

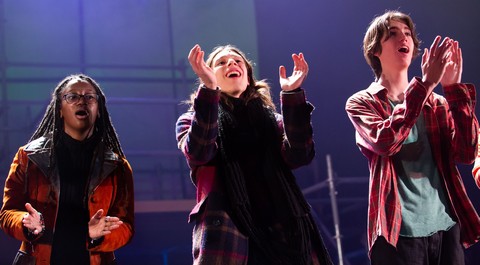

The cast of The Frank Sinatra School of the Arts production of “Rent” (Photo credit: Abe Ariel)

[avatar user=”Chip DeFFaa” size=”96″ align=”left”] Chip DeFFaa, Editor-at-Large[/avatar]

I just got back from seeing Rent at the Frank Sinatra School of the Arts, a respected New York City performing-arts high school founded by Tony Bennett. If I could, I’d go see this production again; it was that rewarding.

I hadn’t intended to write anything about the show when I went; I was just going for my own enjoyment. I don’t write about most high-school or college productions I see; I don’t have the time or the energy to do that. (And I have a million projects of my own to work on.) I also don’t believe it’s fair to judge student productions using quite the same standards used in accessing professional Broadway or Off-Broadway productions. Young people, who are just starting out, naturally don’t have as much experience as seasoned pros; when I attend youth productions I’m not demanding or expecting perfection. But I do enjoy seeing people of any age doing their best, giving their all gladly on stage. That’s fun. I’m happy to be a supportive audience member.

Once in a while, though, I will see a student production somewhere that is just so unexpectedly satisfying—and so unusually impressive for a student production—that I want to write something about it. About a decade ago, for example, I wrote in these pages that the young star of a student production of Guys and Dolls at New York’s LaGuardia High School, Ansel Elgort—who’d never before done a musical–was one of the three best performers I’d ever seen at that school in the last 20 years. He’s since achieved success on stage and screen, and currently may be seen starring in Steven Spielberg’s West Side Story. (I’m proud I gave him his first praise in print, in his first musical! The talent was clearly there. I remember telling him and his Dad after the play that he’d do very well in show business. And the father said, jokingly: “He’d better! We don’t have money to send him to college.” And before long he was working Off-Broadway, then co-starring in the film The Fault in Our Stars, and so on.) I first saw (and mentioned in print) Timothée Chalamet—who has likewise gone on to success on stage and screen, earning an Oscar nomination–in another student production at LaGuardia, Sweet Charity. Sometimes, when you go to see a good student production, you may be seeing a future star.

And New York’s top performing-arts high schools—such as LaGuardia, PPAS, and the Frank Sinatra School–really are extraordinary places. I’ve not found schools to fully equal them in New Jersey or Connecticut. They should not be taken for granted; they’re crown jewels of New York City. They give young artists terrific opportunities to develop their talents. And their shows—like the shows at Juilliard–are always worth seeing. I’d recommend them, generally, to anyone who appreciates theater. You’ll see talented people doing good work, and it won’t cost you much.

But whether or not the various young performers I’ve just seen in Rent at the Frank Sinatra School ultimately choose to pursue careers in show business isn’t really the important thing. They sure came together as an ensemble this spring to beautifully project the spirit of that remarkable musical. Rent is not an easy show to pull off. (Over the years, I’ve witnessed almost as many annoyingly dreadful productions as good ones, and I’ll talk about that, too, in a bit.) But these kids met the challenges wonderfully. I loved their work. And I’m also grateful to them for stirring up so many good memories.

I’ve seen Rent many times in many places since Jonathan Larson first began developing it. I know that particular show inside-out. For a variety of reasons, it is very special to me; and I’m not easy to please. (Nor was the guest I took, who likewise saw Rent from the beginning.) But I wish I could personally thank every student in this production, along with their excellent director/choreographer, Jamie Cacciola-Price, for the joy they gave me. Due to some health issues, I wasn’t certain if I’d even be able to see this production when I ordered my tickets. I ordered the tix, hoping I’d be able to make the show. I’m sure glad that I was able to go. For me, good theater is always good medicine. And I will always remember this performance.

Logan Spaleta (Mark), Luke Studley Roberts (Tom Collins) and Justin Nicot (Angel) in a scene from “Rent” (Photo credit: Abe Ariel)

I hadn’t actually met anyone in the production in person when I entered the Frank Sinatra School to see Rent, although I’d been greatly impressed by recordings that one cast member, Logan Spaleta, has been releasing, which have been getting good play. I knew that he sure could sing, with a nicely soaring, open quality I liked. But I didn’t really know what to expect from the production, overall. This was the school’s first musical in over two years. Everything had shut down due to the pandemic.

However, right from the opening sequence (“Tune Up” through the title song, “Rent”)—which Spaleta (a very likeable “Mark Cohen”), Brendan Dugan (terrifically intense, well-cast as “Roger Davis”) and company carried off with tremendous aplomb–it was clear that Rent was in good hands.

This production was an ensemble success—which is what Jonathan Larson was hoping to achieve—so I’d like to mention every member of the company. Not just the leads, whom I very much enjoyed (Logan Spaleta, Brendan Dugan, Lily Resto-Solano as an appealingly amiable “Mimi Marquez,” Justin Nicot as the insouciant “Angel Dumont Schunard,” Monica Malas making the most of the role of “Maureen Johnson,” Tsehai Marson as her frustrated girlfriend “Joanne Jefferson,” Luke Studley Roberts as “Tom Collins” (who falls for “Angel”), and Matthew Macneal as landlord “Benjamin Coffin III”), but every member of the ensemble: Olivia Summer, Nicholas Martell, Miekayla Pierre, Ben Gluck, Sophia Longmuir, Gabriel Paredes, Isaac Wilson, Isabella Soleil Smith, Daniel Stowe, Jaiden Torres, Monica Malas, Ellistair Perry, Zune Misrra-Stone.

Tsehai Marson (Joanne) and Monica Malas (Maureen) in a scene from “Rent” (Abe Ariel)

The whole ensemble (with music direction by Heidi Best) sounded glorious on the big numbers, from “Seasons of Love,” to “La Vie Boheme,” to “Another Day” (which, if done right, becomes a kind of spiritual experience—and they did it right; it opened my heart). This production’s cast was actually a bit larger than in the original New York production. (There were 15 actors in the original cast in New York; 19 actors in the cast I saw today.) And these Sinatra School kids got a satisfyingly great, rich, full, ensemble sound. Well-blended, well-rehearsed, in tune.

* * *

I also hope these kids realize what a good director they’re working with. Their director clearly understands this musical. He respected Jonathan Larson’s intentions throughout, and he allowed magic to occur. It’s not easy. I don’t know director/choreographer Jamie Cacciola-Price personally. I hope someday I may meet him. But I’m grateful to him for what he helped make happen on the stage here.

Had I known the production was going to be this good, I would have invited some actor friends who’ve done Rent on Broadway or on the road, or some of Jonathan Larson’s old friends and family, who’ve enjoyed seeing other productions with me over the years. However we’ve also been burned from time to time, seeing some notably bad productions of Rent over the years; so I didn’t want to get my hopes up too high when I ordered tickets.

But this was the full show, uncut (not a simplified junior edition for schools), and it felt wonderfully alive throughout. The students performed it with heart and understanding. I believed the characters. I cared about the characters. I liked the characters. The actors were warm and human. The staging was excellent. On balance—and I choose my words with care—this was the best high-school or college production of Rent I’ve ever seen. I sure wasn’t expecting that. But I enjoyed it tremendously. If they had a cast album, I’d be playing it right now.

Brendan Dugan (Roger) and Lily Resto-Solano (Mimi) in a scene from “Rent” (Abe Ariel)

* * *

Seeing this production also brought many good memories for me, because I was there when Rent first came together at the New York Theatre Workshop, Off-Broadway. When the actors were rehearsing that work-in-progress, they had no idea they were part of something that was going to become iconic. They were doing a new show by a writer who was far from well-known, in an out-of-the-way theater on East 4th Street. Jonathan had spent seven years working on Rent. He had stayed with the project even after his original collaborator, Billy Aronson (who actually had the initial idea for the show), had given up on it.

I remember talking with some of the actors working on Rent at the New York Theatre Workshop in January 1996—crowded into a cramped dressing room backstage, all getting the exact same small pay for the original limited-run Off-Broadway engagement. They figured that in a short while they’d be back working full-time at their regular day jobs once again, and Rent would just be a nice memory. No one knew that Rent was going to explode the way it did, transfer to Broadway, and become an international, Pulitzer Prize-winning hit. The most highly anticipated musical in New York, when that season started, actually was Big. The movie Big had been such a mega-hit, everyone assumed that the coming Broadway musical adaptation—boasting the biggest budget in Broadway history up until then—would surely be the year’s biggest hit. No one could have dreamed that the bloated Broadway version of Big—which turned out to be surprisingly sluggish, uninspired, by-the-numbers–would come and go quickly. Nor could they have imagined that a spunky, impudent new musical called Rent at a little East Village theater, featuring a cast of young unknowns, would wind up overshadowing every other production in town.

I remember Daphne Rubin-Vega—“Mimi” in the original cast of Rent—telling me that January in the dressing room how she was worried she might be coming down with a little winter cold; her throat felt kinda scratchy. I said that my throat did, too. She told me she was trying something called echinacea for her throat, adding: “You should try it, too, Chip; it helps.” And I went out and bought some echinacea—which I’d never even heard of before—because she’d recommended it. (I wound up saving that little bottle of echinacea as a reminder of Rent; I still have it.) We were just making some random small talk back stage. Others talked with me about their other jobs. (One worked as a dispatcher for plumbers, of all things. Anthony Rapp—the most experienced performer in the cast–had been working at a Starbucks.) No one had any idea that this little musical they were working on was about to become the theatrical sensation of the decade.

My friend Timothy Britten (“Toby”) Parker—who played “Gordon” and other roles in show—told me he’d made some demo recordings for Jonathan, for free—just helping out a fellow aspiring artist. No one seemed to have money to spare; and helping one another was what you did. He was happy that the show, at least, would help memorialize a few friends of his and Jonathan’s who’d died from AIDS. He kept a picture of one of those friends backstage. (And the real Gordon, whom he was portraying on stage in the life-support meeting scene, had also died of AIDS; the lines that Toby was saying in the play—like “I’m a New Yorker; fear is my life!”–were lines that the real Gordon had actually uttered in life; Gordon’s mom, a sweet woman, loved that her son was, in a sense, part of the play.)

I knew several actors who’d done a reading of Rent for Jonathan a few years before. I brought one of them with me to see Rent when it opened Off-Broadway, figuring she’d be especially interested in seeing how the musical had evolved. She was amazed to see how many songs Jonathan had replaced in the interim, and how some characters had disappeared forever and others had been added. (He had worked hard on Rent for years, while supporting himself as a waiter at the Moondance Diner.) She loved the musical. (And she helped me put together a memorial show after Jonathan died, which his father attended. And she wondered how many more changes he might have made to Rent had he lived longer; he was forever coming up with new ideas.)

Jonathan died unexpectedly in his apartment, due to an aortic dissection, on January 25th, 1996–the night before the very first performance of Rent. He was just 35. His death hit the cast, his friends, and his family hard. And the cast fused into one of the strongest ensemble casts I’ve ever seen, performing with heightened intensity, his words “no day but today” suddenly taking on new urgency. The cast performed with such strong emotions, some nights it was overwhelming. In April, the show transferred to Broadway, packing the Nederlander Theatre for the next dozen years.

I was lucky enough to attend the recording sessions for the original cast albums of both Rent in 1996 and the related musical tick, tick… BOOM! (Jonathan Larson’s autobiographical show about his struggles as an artist) in 2001. For me, it was inspiring to be at those sessions. I took the black-and-white photograph of Anthony Rapp and Toby Parker that I’m sharing here while they were recording “Seasons of Love” for the Rent cast album. I was so happy seeing my friends in what was now the biggest hit in town, singing a song that was quickly becoming a big hit as well.

Anthony Rapp and Toby Parker at the “Rent” original cast recording session (Photo credit: Chip Deffaa)

I saw Rent repeatedly in New York. I took assorted friends and relatives—some loved it, some hated it; it elicited strong reactions. I watched it become the show that everyone was talking about.

Theaters everywhere—community theaters, regional theaters, high-school and college theaters—all were soon clamoring to do Rent, if only because it was such a huge hit on Broadway. They knew the title would sell tickets. An agent helping represent the Jonathan Larson estate (who for a while was also my agent) sure had his hands busy! Everybody was dying to do Rent!

Or so they said. Everyone was saying they wanted to do Rent, because it was such a huge hit. But what I discovered, as I began going to see actual productions being mounted in various places, was that directors of these productions often made unauthorized changes, trying to make Rent less confrontational, trying to turn it into something more conventional. (And less interesting!)

Some were improperly eliminating (without permission) scenes or lines they feared might offend older theater-goers. (When you license a play, you sign a contract saying you will not make any unauthorized changes; but they were scared Rent went too far for their audiences.) And to me, these oddly sanitized, diluted versions of Rent that they mounted no longer really felt like Rent. It angered me because directors making unauthorized changes to their productions were muting Jonathan Larson’s message. And he had worked so hard on the show. (As his sister Julie, who’s so admirably devoted herself to his legacy, has often said: “Jonathan worked very hard for 15 years to become an ‘overnight success.’”)

I watched in dismay as even good theaters, which should have known better, tried to offer tamer, more conventional, family-friendlier versions of Rent that undercut what Larson was saying. Some producers said they didn’t want to “upset” anyone. (Jonathan, of course, was fine with good art being upsetting sometimes; that’s essential.)

So maybe they’d drop from their production of Rent a number like “Contact” as being too “in-your-face.” One production, crazily, managed to cut all references to AIDS. The popular Sharon Playhouse in Connecticut eliminated “controversial” words, as if panicked by thought that some patrons might walk out if they heard words like “erection” or “masturbation.” (Did they really think no one’s ever heard of these words?) I was so disappointed by their bowdlerized version of Rent. And their efforts were futile; those who were going to be offended by words like “erection” or “masturbation” were still likely to find offense in the story itself, even if some words were cut.

The Westchester Broadway dinner theater—a place I loved, which for decades mounted satisfying productions of so many traditional older Broadway shows–made sure that in their woefully mis-directed production of Rent, the same-sex couples did not even display affection. They had the gay lovers “Angel” and “Tom Collins” sing “I’ll Cover You with Kisses” while standing as far apart as possible–at opposite corners of the stage!–to ensure that they could not possibly kiss, hug, or touch in any way. That struck me as sheer madness! The theater clearly was nervous about depicting homosexual love. They tried to keep distance between “Angel” and “Collins. And—they weren’t discriminating!–they minimized any physical contact between Roger and Mimi, and Maureen and Joanne, as well, giving the whole production a sterile feel. Their staging sent the wrong message—as if they’d decided to present Rent because it was the show right now, but they were sort of holding their noses while presenting it.

I took Victoria Leacock Hoffman, who’d been Jonathan’s girlfriend/best friend/biggest champion, to see that production with me. And after the performance, we went back stage and she introduced herself. The cast members all recognized her name; they were using a published edition of the script that included an introduction she’d written. And Victoria knows Rent as well as anyone alive. She’s seen it countless times and has directed productions herself, doing it exactly as Jonathan intended. And boy, did she let that company have it! She was justifiably outraged that the production had eliminated so much human contact. It was essential, she impressed upon the cast, that the lovers “Angel” and “Tom Collins” not just sing the words “I’ll Cover You with Kisses,” they had to kiss; there was nothing shameful in kissing! If the director wasn’t comfortable with the basic concept that love is love, whether it’s gay or straight, he shouldn’t be doing Rent. And she went through place after place in the script where Jonathan had wanted there to be some kind of contact between people–whether the characters were gay or straight—here a kiss, there a hug, here a touch…. One specific place after another. She sure was clear—speaking on Jonathan’s behalf—on what Rent was about. I enjoyed watching her educate them in her own fierce way more than the show itself that night. I was so proud of her!

I might add, by way of contrast, we had a much happier experience up in Trumball, Connecticut, watching kids at Trumball High School capture better the loving essence of Rent, after their school principal had tried to cancel Rent altogether claiming the musical was too controversial. But the high-school kids protested long and hard until they finally won the right to perform Rent (the school edition, anyway). And a bunch of us–including Victoria, and Jonathan’s father, and assorted friends and relatives of Jonathan’s–drove up to show support for the kids; that was one great night.

Many people, though, simply seemed to find Rent too controversial to do as written. They’d present it but try to muffle its messages.

Every time I thought I’d seen it all, some producer or director seemed to find still another way to mess up Jonathan’s work—even the ones who didn’t change a word.

Here’s one example. One school in Paterson, New Jersey had the whole cast pre-record all of their songs. Then they had the actors awkwardly sing along on stage in performance to their pre-recorded vocals. It looked and sounded so horribly fake as they worked their way through some of Jonathan’s great music—and Jonathan was all about being real and taking chances—that I wanted to walk out. But I was sitting in the front row and there was no way for me to slip out unobtrusively. And so I suffered, watching kids sing along like robots to their pre-recorded tracks. (I’ve now seen this done at a few places; I sure hope it doesn’t become a trend. “Live” theater should be “live.”) Singing should be expressive and natural, and a joy. But there wasn’t much joy on that stage that night.

* * *

Seeing so many different flawed presentations over the years made me doubly happy that the cast at the Frank Sinatra School did so much so well. They got the overall feel of Rent beautifully, as Jonathan had intended. (Happily, even the kisses were all there, and felt natural and right, just as Jonathan felt they should be! And the “controversial” words were all there, too, as written.) The director and the cast respected the material, which is of course how it should be. Jonathan Larson would have loved the production.

Not all directors have the wisdom or decency to respect material. They will make unauthorized changes to scripts, sure that they can “improve” any scripts by their inappropriate revisions.

I saw one college production of Rent in which, instead of starting properly on Christmas Eve with Mark filming his fellow starving-artist, Roger, the director chose to graft on a brief, brand new introductory scene that he’d created. And in his revised version of Rent, the musical opened with a successful, well-dressed, middle-aged filmmaker, “Mark Cohen,” recalling his wild and crazy youth and how he first got started as a filmmaker… and then the whole subsequent story of Rent was offered to us as a comfortably nostalgic flashback; instead of feeling fresh and edgy and challenging, Rent became a memory-piece in which a successful older man, wearing a suit, recalls contentedly the apparently long-gone rebellious spirit of his youth.

There were some good performances in that oddly revised production of Rent (which was done at Hofstra University), and I’m glad I saw it. I cheered for the performers. But the newly created opening scene felt wrong. It deprived the story of its immediacy and urgency. In this revised version, we were watching an evening of pleasant recollections. The newly added opening scene had the effect of making the musical say something Jonathan had not chosen to say—that “Mark” will live to grow old and be successful, and wear a suit, and be content with his conventionally successful life. (Maybe the director wanted the comfort of believing that.) But Rent, as written by Jonathan Larson, promises no such thing.

As they sing in Rent: “There’s only now, there’s only here…. No day but today.” That is the key message of Jonathan Larson. Jonathan does not know what the future will have in store for “Mark Cohen” (who is a thinly disguised version of the ever-observant Jonathan) or anyone else. Some in their circle may live, some may die, some may move away; that’s reality.

“There’s only now, there’s only here,” insisted Jonathan, who died unexpectedly before those terrific lyrics would be heard by the public for the first time. And that sense of urgency—that feeling that “I need to make the most of this moment because tomorrow is not promised”—is a recurring theme throughout Jonathan’s work. Which was sacrificed when the director at Hofstra imposed that new (and all-too-pat) introductory scene on the musical, turning the show into a pleasant recollection. And giving “Mark” a kind of happy ending that Jonathan, in real life, certainly never got to experience.

Sidebar. If the director and students at the Frank Sinatra School ever want a good intimate musical to try—one that could be mounted in any black-box kind of space–they should consider doing a production or reading of Jonathan Larson’s tick, tick… BOOM!, a fine, small-cast show about Jonathan’s struggles as a starving artist in the years leading up to Rent; it is, in a sense, a companion piece to Rent, drawn from some of the same experiences. After Jonathan’s death, Victoria Leacock Hoffman made it her top priority to get that show produced, so people would more completely understand and appreciate Jonathan’s genius. (And hear some music of his that otherwise would have remained unknown.) When the film version of tick, tick… BOOM! was completed in 2021, I went to a special screening of the film with Victoria and various other friends and family of Jonathan Larson, and it prompted so many reflections on life for all of us. That wonderful film—which I recommend highly–captures the sensibility of Jonathan Larson very well (far better than the poorly directed film version of Rent, which didn’t have the bite or sass or spirit of the original stage production; the director of the film had softened Rent a lot—making it more about his vision than Jonathan’s—and turning it into, I felt, a kind of Rent-Lite).

* * *

There are a few other random things I liked about the Frank Sinatra School’s production of Rent, which I’d like to talk about. I saw the show in April of 2022. The students began rehearsing it way back on September 10th, 2021. They invested 1,000 hours of their lives rehearsing Rent over a seven-month period!

Very few schools in the world give kids a chance to spend anywhere near that much time preparing a production. Professional actors never get the luxury of that much rehearsal time. (Rehearsal time is expensive!) Off-Broadway productions, like the original production of Rent that I saw at New York Theater Workshop, often make do with just a few weeks of rehearsal. I mounted the first version of the show that became my Off-Broadway hit George M. Cohan Tonight! in three weeks, writing the show while directing it in those three weeks of rehearsals, finishing the last pages of the script just before the first performance. The first time the show was done in Korea, my Korean producer budgeted for three months of rehearsals—unheard of in America!—and that long rehearsal period allowed for a lot of fine-tuning. I tend to thrive on stress myself, and like working under pressure. But it’s also really nice sometimes to have a long rehearsal process and get things just right. I envy the kids at the Frank Sinatra School getting 1,000 hours of rehearsal time to work on the show. It paid off.

Even brief scenes within the show had a well-crafted feel. Miekayla Pierre had a small role as a homeless person who tells off Mark Cohen when he tries to film her: “I don’t need no goddamn help from some bleeding-heart cameraman. My life’s not for you to make a name for yourself on…. It’s not that kind of a movie….” Not a lot of lines but she made sure they hit hard so the scene had maximum impact. She had fire in her. The well-rehearsed scene couldn’t have played better. And it grabbed us.

I saw a production of Rent in Wayne, New Jersey that had some very talented actors in it (one of whom has gone on to record with me on albums I’ve produced). But the Wayne production appeared under-rehearsed, as if they hadn’t had time to properly block each scene. It looked as if the director had simply told the cast things like: “Everyone just walk out on stage and sing the song.” And the actors would be standing around downstage in some sort of random-looking clump and sing. The production ended like that, with everyone in the show—except for the character of “Angel,” who had died of AIDS—just sort of walking on stage in a raggedy kind of group, and singing the finale. I felt bad for the cast because it looked so awfully casual, as if no thought had been given to composition, and also because the actor playing “Angel”—who was the most impressive actor in that particular cast—didn’t get to participate in the finale. And the finale is so important. As George Burns taught me, “Nothing is more important than how you begin and end a performance. You can mess up in the middle but if you end strong enough, they’re only going to remember that.”

And this is one other reason that I like the way Jamie Cacciola-Price directed Rent at the Frank Sinatra School. He has a good eye for visual composition on stage. The actors were well placed, always. He understands pictorial story-telling.

And I’ve never seen a more attractive final grouping in any production of Rent—professional or amateur—than he devised for the finale. He had every member of the company (including “Angel,” who often seems to wind up getting left out of the finale in productions) wisely positioned. High above the others on stage—and now resplendently dressed in white—was “Angel,” looking like a heavenly angel watching over those below.

That may sound corny, but the whole scene was gorgeously composed, it was stunningly lit, and it took my breath away. (I wish I had a photo of that final image to show you.) If I were running that school, I’d give the director a raise just for the way he handled the finale. Everyone in the cast, including “Angel,” was perfectly placed. The singing—“No day but today…”–was pure and true. And then—bam!–it was all over. My God! What a finish! Just perfection. I didn’t want to leave.

* * *

I might add, the production values at the Frank Sinatra School of the Arts were first-rate. These kids were performing in a state-of-the-art 800-seat theater with high-quality lighting equipment, audio equipment, and projections—all much better than anything Jonathan Larson ever got to work with in his lifetime.

Tony Bennett donated the initial funds that made possible the creation of this school, 20 years ago; and his foundation continues to provide ongoing support. The school is located in Astoria—Bennett’s home town—right across the street from the Kaufman Astoria movie studio. (Any New York parents reading this article who have teenage children with a passion for the performing arts should consider this school. You can read about the process of applying, which includes auditioning—it is a selective school–on their web site.)

The lighting for their production of Rent (designed by Andre Vazquez) was as good as I’ve ever seen in any student production. A character might be showcased so effectively by three spotlights I didn’t want the moment to end; it simply looked so good.

The sound design for this student production was actually better than Rent had on Broadway. It was often hard to understand all of the words being spoken or sung at the Nederlander Theatre. That didn’t really seem to matter too much to fans, since so many audience members knew the songs so well already from the cast album. But the sound wasn’t clear, and plenty of words got lost. And when Rent first hit Broadway—it was such a phenomenon–fans cheered and clapped and hollered so loudly for numbers they sometimes drowned out the actors when they began to speak again. (When my brother and his wife went to see the Broadway production of Rent, they told me they couldn’t really follow the story because so many words were unintelligible; they enjoyed the melodies and the energy, they said, but couldn’t make much sense of the story. My brother’s wife didn’t even realize that “Angel” was a man in drag; she thought Angel was a woman! Their kids, who’d already seen the show with me and listened to the cast album a lot, had to explain the plot to them, after the fact.) Audio engineers for the Broadway production of Rent wanted to keep the volume up (to suggest some of the excitement of a rock concert, rather than the quieter sound of a typical Broadway musical), even if it meant sacrificing some degree of clarity. Happily, it was easier to understand the words at the Frank Sinatra School of the Arts than it was on Broadway (or, for that matter, at most other places where I saw productions of Rent over the years). Jonathan Larson used to say that in the end, how good his scores sounded would always depend a lot on how good the audio engineers were. There seemed to be some pretty good engineers working on this show here.

* * *

I really wished I could have seen the show a second time. (I would have loved to have seen the alternates and understudies as well.) Victoria Leacock Hoffman wrote out a message of encouragement to the cast, which I passed along on her behalf, giving it to Logan Spaleta to give to the director. I was happy to see Logan on stage, after having enjoyed his recordings so much. I’m a pretty good judge of talent, and while watching him perform, with a wonderful light in his eyes, I thought he was someone I’d cast in an instant if I were directing a play that that had a part suitable for him. He’s got that spark!

I wish everyone well and hope that someday I may be telling people that I saw, say, Brendan Dugan or Lily Resto-Solano or Justin Nicot or whoever at the start of their careers. The friend that I took to the show bought me a Rent tee-shirt in the lobby, as a memento of a good day, and I’m wearing it now. I want to hold onto the spirit of the show a little longer.

Tshehai Marson, Logan Spaleta and Daniel Stowe sing “Seasons of Love” in a scene from “Rent” (Photo credit: Abe Ariel)

I’m home now, pleasantly exhausted, and I still have lots of work to do tonight. (The adrenalin is carrying me!) In a few days, we’ll be launching a new album I’ve produced, “Chip Deffaa’s My Man,” and I have to reach out to some of the people connected to it. I write Anthony Rapp (who originated the role of “Mark” in Rent on both stage and screen), to thank him for letting me include a song that he wrote on the new CD, which I’m mailing to him at his home. I write ebullient Chad Anthony Miller, who was the first person I recorded for this album—so long ago that he’s probably half-forgotten the recording session–to tell him to watch for the CD.

It’s funny, though, because normally when I’m launching a new album—I’ve produced 35 albums to date, besides writing books and plays—I’m so excited, that’s all I can think about. But I’ve been so entranced by this good production of Rent, I want to tell everyone I’m contacting tonight about Rent rather than the album. I fight the urge, figuring that Chad Anthony Miller from Lubbock, Texas, will probably be much more interested in knowing that his fine recording will finally be coming out than in hearing how great a production of Rent at the Frank Sinatra School of the Arts was.

But there’s something about this production that just got to me. I’m still in a Rent frame of mind. And I want to talk to everyone about it. I tell Victoria how good the production was; I forget to tell her that the new CD I’m about to release is dedicated to her! And it’s on the way to her in the mail.

I tell one fellow on the new CD, who’s friends with Idina Menzel, that I just saw a gal (Monica Malas) playing the role that Idina originated in Rent, and I’m sure she will play that role some place professionally someday; she’s already so polished and self-assured. I actually enjoyed her more than Idina.

And I write one friend who played “Mimi” in a national tour, to tell her how Lilly Resto-Solano effectively interpreted the character the way that she had—letting us see the softer, kinder, more vulnerable side of “Mimi”—rather than the way others more often choose to play the character (making her tougher, warier, more aggressive); it fascinates me the way different approaches to a character can be made to work.

I touch base with another fellow who records with me, who’s currently working as an understudy in a show; he’d asked me, as a favor to him, to pay particular attention to any understudies in the cast of Rent, since he believes understudies always get ignored. (Poor baby!) I tell him that Daniel Stowe, listed as an understudy in the program, was actually quite good in the ensemble parts he played at the matinee I saw, making the most of them, and I’m sure I’ll see him in bigger roles in the future; I look forward to that. But my friend doesn’t want to hear about any of that tonight. He’s excited to tell me instead that an actor he’s understudying happens to be out right now—“and of course I hope he gets better real soon, Chip. But I’m going on for him until at least Thursday, maybe longer; you must come!” Ah, show business!

But Rent has stirred a lot of memories for me. I even call the man who directed me in plays when I was these kids’ age, to tell him how good the show was. He’s 93 and he’s still a great friend. I presented one of his plays in New York a few years back, and had him make a cameo on a recent album I produced (“Irving Berlin: Sweet and Hot”). I tell him that the kids in this production made me remember the shows I did with him.

I really wish I could see Rent again. Or play a cast album. (When schools do shows of mine, I always give them permission to make limited-distribution cast recordings or videos.) And I’m already looking forward to seeing the next musical at this school, a year from now. I won’t write about; I’ll just be there as an anonymous audience member for the sheer pleasure of it, knowing the good work they do at this school. I hope I get to see it!

I enjoyed your review and am going to go see the play. It was never really explained of how the musical was to be enjoyed or how the writer wanted to get his vision portrayed.