American Dance Platform: Fist and Heel Performance Group & Martha Graham Dance Company

Two very different dance troupes share one program.

Anna, Schon, Raja Feather Kelly, Dwayne Brown, Rhetta Aleong, Lawrence Harding, Paul Hamilton and Clement Mensah of Fist and Heel Performance Group in a scene from “Moses(es), Moses(es)” (Photo credit: Peggy Woolsey)

[avatar user=”Joel Benjamin” size=”96″ align=”left”] Joel Benjamin, Critic[/avatar]Could there be two more different dance companies than Reggie Wilson/Fist and Heel Performance Group and the Martha Graham Dance Company? The American Dance Platform series at the Joyce Theater, sponsored by the Harkness Foundation and curated by Walter Jaffe and Paul King, is presenting a week of similarly diverse pairings to highlight the diversity of today’s dance scene. This opening program certainly filled that bill.

Reggie Wilson has been combining dance and cultural anthropology for many years. His troupe, Fist & Heel Performance Group, is a living testament to his passion with “Moses(es), Moses(es),” his full-company work, a living and breathing example of his philosophy. In his program notes, Mr. Wilson explained that this work was based on “the many iterations of Moses in religious texts, and in mythical, canonical and ethnographic imaginations,” a big subject that, unfortunately, doesn’t lend itself to a dance interpretation. In fact, Mr. Wilson’s description, not withstanding, it would be difficult to find any reference to that Jewish Biblical giant in “Moses(es), Moses(es),” except when the entire company sang a song whose only word was “Moses.”

For “Moses(es), Moses(es),” the stage was littered for some reason with piles of tinsel which Mr. Wilson painstakingly stuffed into a large red wheelie suitcase as his company members entered the stage, dressed casually in costume by Naoko Nagata, in variations of red. (Mr. Wilson was in a white jumpsuit.) The music, which ranged from soundscape tones to spirituals to percussive African, was by Mazaher, Aly Us, the Growling Tiger and the Blind Boys of Alabama. The work was constructed in several discrete sections, signified by distinct light changes (designed by Jonathan Belcher and well executed by Carrie Wood) and arraying of personnel, although the range of steps—stomps, leaps, hip undulations, ballet turns—didn’t vary much from section to section.

Entering singly, the members announced their names and how long they had been with the troupe, breaking down barriers between them and the audience. They proceeded to perform simple movements, centered on a stomping walk. They formed circles, chanted and occasionally moved in a ways that approximated slow motion or being dangled like marionettes. Two couples occasionally occupied different parts of the stage. The dancers formed lines. The men leaped about. The steps became a mash up of African, modern and ballet. Most of the dancers also sang or hummed as they danced.

Even if the Moses theme wasn’t explored in any depth, the troupe did come across as a pleasant community of very differently sized artists with an ardent commitment to their leader.

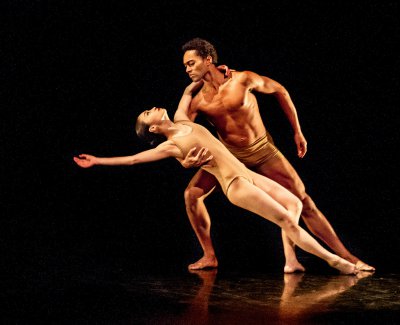

Xiao Chuan Xie and Abdiel Jacobsen in Martha Graham “Pagarlova Variation” (Photo credit: Brigid Pierce)

The Martha Graham Dance Company managed to explore many emotional states in the two works it presented. The first, “Steps in the Street” from 1936 is somehow still fresh in its abstract portrayal of group angst in three sections: Devastation—Homelessness—Exile. To a surprisingly upbeat, pounding score by Wallingford Riegger, the women-only cast, clad in severe, long black dresses, took the stage in formal lines, their bodies twisted, elbows at odd angles, heads tilted stiffly, mutely expressing a combination of anger and sorrow. An opening solo, performed in silence, set the mood. Xin Ying angrily stepped, heel-toe, in classic Martha Graham style, writhing, her dress flying about as she jabbed her legs, dipped to the ground and ran about. Even though there was a museum exhibit feel about the technique, the women were fully into working with each other to express the work’s darkness. The legendary lighting, originally designed by Jean Rosenthal, Graham’s longtime collaborator, was re-created by an anonymous, but hardworking, technician.

The “Lamentation Variations” make up a series of 12 experimental works by notable modern dance choreographers based on Martha Graham’s famous, oft-satirized, distillation of grief. In the original, as evidenced by a very distorted old filmed version projected onto the back wall, Graham, encased in a tube of soft, purple jersey material, bent and twisted, opened and closed her legs, tensing her feet into distorted shapes. The three Variations shown on this program had only passing references to the original—color of costumes, intense emotional state, deep self-involvement—but had choreographic merits of their own.

The first Variation, choreographed by Bulareyaung Pagarlava used a Mahler symphonic song to accompany a dance that pitted a single women, Mariya Dashkina, against three virile men—Lloyd Mayor, Ari Mayzick, Ben Schultz—who lifted her, chased her and made outrageously beautiful shapes.

The second Variation, created by Sonya Tayeh used a rhythmic chanting score by Meredith Monk. Seven dancers, the four women costumed by Barbara Erin Delo, in chic purple leotards, the three men, bare chested over loose black pants, performed a series of duets and trios, with lots of rolling on the floor, the men balancing off each other, the women dancing with each other and lifted by the men. For some reason, this second Variation ended with a female soloist flailing in a dimming spotlight. Why she left the group and why she was unhappy was never explored.

The third, by Larry Keigwin to Chopin, had the entire company standing in rows, apparently staring intensely into imaginary mirrors, adjusting their facial expressions and hair, posing timidly or boldly, while several broke into impassioned solos. It was an interesting germ of an idea, undeveloped in the short space of the music, but effective as a statement of modern self-involvement.

These three short works were helped by some brilliantly effective lighting: Nicholas Houfek (Tayeh) and Beverly Emmons (Pagarlava and Keigwin).

The dancers under the direction of Janet Eilber are solidly professional, good looking and dedicated.

American Dance Platform (January 12-17, 2016)

Joyce Theater, 175 Eighth Avenue, in Manhattan

For tickets, call 212-242-0800 or visit http://www.joyce.org

Running time: one hour and 45 minutes including one intermission

Leave a comment