Remembering George Wein

A tribute to the man who founded the modern music festival.

George Wein at his piano

[avatar user=”Chip DeFFaa” size=”96″ align=”left”] Chip DeFFaa, Editor-at-Large[/avatar]

George Wein, who died peacefully at his New York apartment at the age of 95, was the founder of the modern music festival. His contributions to pop culture were enormous. I liked him very much. He was easy to talk to, always candid and frank in our talks, and he was wholly committed to the music he loved. Starting in the early 1950’s, he created the Newport Jazz Festival, and followed that with assorted other festivals: the Newport Folk Festival, the Kool Jazz Festival, the JVC Jazz Festival, the Grand Parade du Jazz (in Nice, France), the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival, and more.

The titles of his festivals might change from time to as he found new corporate sponsors; the Kool Jazz Festival, for example, became the JVC Jazz Festival. (And he pioneered that concert, too–getting big corporations to subsidize concerts in return for naming rights.) His festivals in New York (which I simply thought of as George Wein’s festivals, as different corporate sponsors came and went) were for many years my favorite part of summers in New York. They were huge events–added lots of life to the city–and drew countless tourists.

George Wein with Duke Ellington and Erroll Garner

But all of the various pop music festivals that sprang to life in the U.S. and abroad after Wein’s early successes with the Newport festivals happened because he paved the way, because of his concept of a music festival. (Without him, there would never have been, for example, a Woodstock.)

He started as a Boston jazz club owner and pianist, and imaginatively improvised festivals that–at their best–felt like a wonderfully satisfying cross between a concert and a party. I liked his late wife Joyce, too, whom he also credited as his partner in every sense. She worked with him on the festivals, sharing his love for the musicians, and helping him find the right balance between idealism (simply celebrating the artists you love) and practicality (selling enough tickets and keeping costs in check so that the festivals could survive another year).

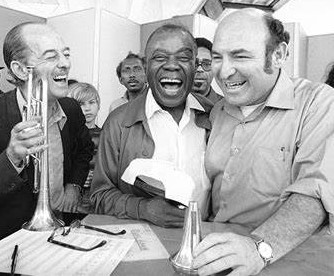

George Wein with Bobby Hackett and Louis Armstrong

I traveled to Newport and New Orleans to enjoy his festivals, as well as, of course, his festivals in New York. (I still have tee shirts from his festivals, going back to the 1970’s.) Sometimes he simply booked artists to do a set of music of their choice. But some of the most memorable moments occurred when he would put together artists for all-star gatherings that would not have occurred except for his input as a producer, and his knowledge and good taste. I treasured being able to see, thanks to him, jazz greats interact who might never otherwise appear on stage together.

And he never stopped playing piano. I loved the music that he and his own all-stars would make.

Even 25 or 30 years ago, when his festivals were major events–attracting huge crowds in New York, Newport, New Orleans–he voiced fears to me about the future of the festivals. He told me he worried because so much depended on things beyond his control. Finances were more precarious than outsiders might imagine, he suggested. So much depended on finding and holding on to corporate sponsors, who didn’t necessarily share his passion for the music. And he also had to worry about security and crowd control at outdoor concerts. (Unruly audiences got him kicked out of Newport for a spell.)

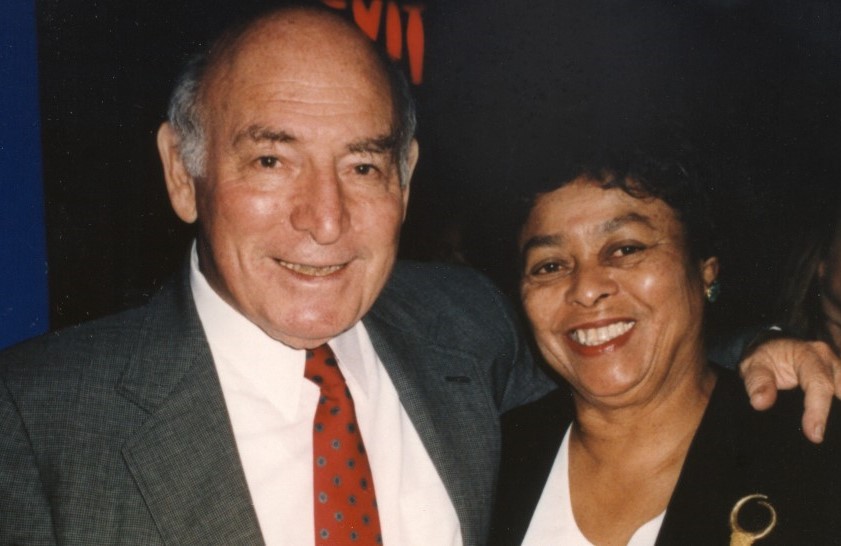

George Wein with wife Joyce

He also told me that he could book the best musicians in the world but if the sound engineers did a poor job, a concert could flop. And finding enough good sound engineers wasn’t always easy. I remember him telling me, “I might hire a young sound engineer who’s done good work with some rock bands, but he’s never before worked with a big swing band; he didn’t grow up with big bands, like I did. He doesn’t know what a big band should sound like. And that one engineer can make 18 big-band musicians sound bad.” He worried, too, he told me, that more jazz greats were dying off than were coming up. It hit him hard when, for example, Ella Fitzgerald died. He liked and respected the young jazz singers coming up, he told me; but none of them could connect with a huge concert audience the way Ella did.

After Wein’s wife died, he began cutting back on his own activities, turning more and more responsibilities over to others, hoping he might be able to serve in more of an advisory capacity. But a great deal always depended on his own taste and vision, and drive.

A tribute to the man who founded the modern music festival.

The photos I’m choosing show him with jazz artists Bobby Hackett and Louis Armstrong; with Duke Ellington and Erroll Garner; with his wife, Joyce.

Leave a comment