Remembering Robert Clary: From the Concentration Camps to Broadway and Hollywood

Robert Clary, who scored notable successes on Broadway and TV, felt his abilities as an entertainer helped him to survive the Holocaust. His parents and most of his siblings were killed in Nazi concentration camps. He was spared because he was healthy enough to work, and one of his jobs at Buchenwald was performing in shows for the amusement of the SS.

Robert Clary on television’s “Hogan’s Heroes” (Photo credit: courtesy of Brian Gari)

[avatar user=”Chip DeFFaa” size=”96″ align=”left”] Chip DeFFaa, Editor-at-Large[/avatar]

Robert Clary, who’s died at the age of 96, may be best remembered as insouciant Corporal Louis LeBeau on the hit sitcom “Hogan’s Heroes.” He was the last surviving member of the original cast of that television show, which aired on CBS -TV from 1965-1971, and continues to be shown in reruns today on the “Me TV” network. He appeared in all 168 episodes. (Our thanks to singer/songwriter Brian Gari, Clary’s nephew, for the photos and information he’s provided.)

Clary made his mark, too, on Broadway in the hit revues Leonard Sillman’s New Faces of 1952 and La Plume de Ma Tante. (He also appeared in the Broadway musical Seventh Heaven, which was a flop despite a strong cast including Ricardo Montalban, Gloria DeHaven, Chita Rivera, Clary and Bea Arthur.)

In a professional career that began when he was a boy of 12 in his home city of Paris in 1938, he had far more credits as a performer than can be listed here. A Holocaust survivor, he gave lectures on the Holocaust throughout the US and Canada in his later years, even after he’d stopped taking acting jobs.

Robert Clary (March 1, 1926 – November 16, 2022) was the youngest of 14 children in a Jewish French family. After the Nazis invaded France, the Nazis began deporting Jews from France to concentration camps. When Clary, his parents and his siblings were herded onto trains, they were simply told they were being re-settled elsewhere. He did not realize, at that time, that they were being put onto trains taking them to death camps.

Robert Clary and the company of “Hogan’s Heroes” (Photo courtesy of Brian Gari)

He was separated from his siblings and his parents; he did not learn until after the war was over that his parents and most of his siblings had been killed almost as soon as they had arrived at the camps. He was spared from immediate execution only because (as he explained in his lectures years later), he was a reasonably healthy 16-year-old male; the Nazis thought he should be put on a forced-labor detail. The Nazis figured they could use him as a worker for as long as his health held up.

At the Nazi concentration camp at Ottmuth, in Upper Silesia (now Otmet, Poland), he was tattooed on his left forearm with the identification number “A5714.” He was subsequently transferred to Buchenwald concentration camp. When the guards learned he had been a professional entertainer before the war, they gave him an additional duty. He was forced to entertain SS soldiers every other Sunday, accompanied by an accordionist. He didn’t like singing for that audience, but had no choice.

He later recalled: “Singing, entertaining, and being in kind of good health at my age–that’s why I survived. I was very immature and young, and not really fully realizing what situation I was involved with … I don’t know if I would have survived if I really knew that.”

He also commented, concerning his time in the concentration camps: “The whole experience was a complete nightmare, the way they treated us, what we had to do to survive. We were less than animals. Sometimes I dream about those days. I wake up in a sweat terrified for fear I’m about to be sent away to a concentration camp. But I don’t hold a grudge because that’s a great waste of time. Yes, there’s something dark in the human soul. For the most part human beings are not very nice. That’s why when you find those who are, you cherish them.”

Eddie Canter and Robert Clary (Photo courtesy of Brian Gari)

After the war, he made a name for himself as a song-and-dance man in France. He came to the US in 1949, working in nightclubs when he could. Master entertainer Eddie Cantor—whose kindness to him Clary always cherished–championed him, giving him opportunities to do sketches and songs with him on television’s “Colgate Comedy Hour,” a major program of early television.

A beloved entertainer, with 50 years of experience as a star of stage, film, radio and TV, Cantor liked promoting younger performers he’d discovered. His successful proteges included Deanna Durbin, Bobby Breen, Dinah Shore, and Eddie Fisher. Cantor enjoyed helping young artists he believed in. He could give them exposure on radio and TV. He could put in a good word for them and help them find work in nightclubs, resorts, or shows. And Cantor—who’d been the first major American star to speak out strongly, publicly against the Nazis (and Americans who were sympathetic to them)—also had a soft spot for Clary as a Holocaust survivor.

Clary became friends with Cantor’s whole family—Cantor’s wife, Ida, and their five famous daughters, Natalie, Marjorie, Edna, Marilyn, and Janet. Clary grew especially close to Natalie; their friendship eventually turned into a romance, and they wed.

Clary scored a great success on Broadway in Leonard Sillman’s New Faces of 1952. My father, who enjoyed that show, recalled Eartha Kitt and Robert Clary as the standouts in the cast of largely-unknown up-and-coming performers that also included Paul Lynde, Alice Ghostley, Carol Lawrence, and Ronny Graham. None of the performers were yet big names. And the smart, fast-paced revue gave them important exposure. (My father noted that this was an especially good revue, in a time when revues were still a staple of Broadway. He missed the revues when revues fell out of fashion on Broadway.) Producer/writer Leonard Sillman, whose various New Faces revues enlivened Broadway from the 1930’s through the 1960’s, helped advance the careers of plenty of talented newcomers over the years, beginning with Henry Fonda and Imogene Coca, the standouts in Sillman’s first revue in the series, New Faces of 1934.

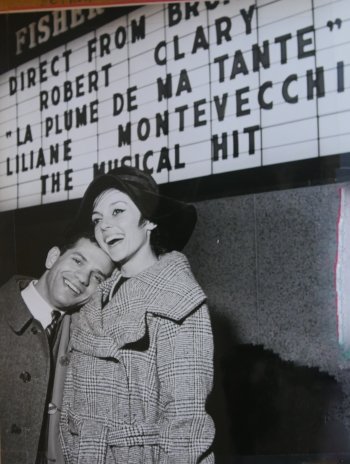

Robert Clary with co-star Liliane Montevecchi in the post Broadway tour of “La Plume de Ma Tante” (Photo courtesy of Brian Gari)

After New Faces, Clary found work making guest appearances on television variety shows and sitcoms. He scored another notable Broadway success when he joined the cast of the hit revue La Plume de Ma Tante, which played at the Royale Theater from 1958-60. He stayed with the show in its post-Broadway tour. The photo shows Clary with co-star Liliane Montevecchi under the marquee of Detroit’s Fisher Theater, when La Plume de Ma Tante played there (“direct from Broadway,” as the marquee says), after the Broadway run ended. Note that Clary has top billing—he is the only cast member to receive billing above the title of the show; Montevecchi is billed below the title.

Clary achieved his greatest commercial success as ebullient Corporal LeBeau on the sitcom “Hogan’s Heroes.” LeBeau played a captured French serviceman, being held in a German prisoner-of-war camp. (The series covered the exploits of an international group of Allied prisoners, working covertly to defeat the Nazis.)

Clary almost quit “Hogan’s Heroes” early in the first season, because he felt his talents were not being utilized well and he was not being given enough to do. But a director talked him out of quitting, noting that he was in a hit show and, over time, he’d find he’d be showcased well. The series ran for six seasons, and Clary wound up getting plenty of good opportunities as a performer.

Robert Clary and nephew Brian Gari (Photo courtesy of Brian Gari)

I learned from Brian Gari, Clary’s nephew, that the “Me TV” network honored Clary by dedicating Thanksgiving-week “Hogan’s Heroes” programming to him. The network rebroadcast what they termed “fan-favorite best episodes of “‘Hogan’s Heroes” that highlight Cpl. LeBeau,” The episodes they selected for their Thanksgiving week tribute, all prominently featuring Clary, included: “Lebeau and the Little Old Lady,” “Gowns by Yvette,” “Man in a Box,” “The Scientist,” “The Gypsy,” and “Cuisine à la Stalag 13.”

And Clary made some lasting friendships in his six years on the show, particularly with such fellow performers as Werner Klemperer (“Colonel Klink”) and Larry Hovis (“Andrew Carter”), with whom he enjoyed singing songs on breaks during the shooting.

After “Hogan’s Heroes,” Clary kept busy with appearances on talk shows (including those of Mike Douglas, Merv Griffin, and Dinah Shore), game shows (“Stump the Stars,” “The Match Game”), soap operas (“Days of Our Lives,” “The Bold and the Beautiful,” “General Hospital,” “The Young and Restless”), TV series (“The New Adam-12,” “The Munsters,” “Love thy Neighbor,” “Arnie,” “Fantasy Island”), and TV movies (“Matisse and Picasso,” “The Legendary Curse of the Hope Diamond”).

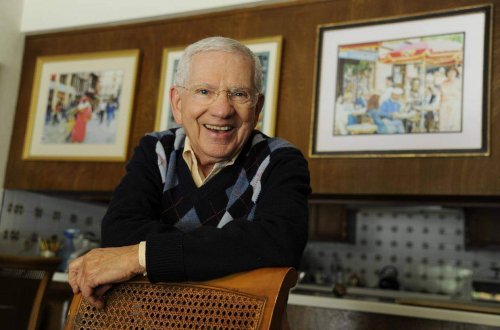

Robert Clary in later years (Photo courtesy of Brian Gari)

Following the publication of his memoir, From the Holocaust to Hogan’s Heroes: The Autobiography of Robert Clary in 2001, Clary began giving lectures on the Holocaust. He did not want the horrors of that period to be forgotten with the passage of time.

When an interviewer for the Television Academy asked Clary, late in his life, how he’d like to be remembered, he replied, “I don’t care. I really mean that. I really don’t care. They will remember me as a nice person? Fine. Remember me as a dirty Jew? Fine. I don’t care because I won’t be here. I’m not going to worry about it. … When I’m dead, I’m dead, who cares? I’ll never know. Nobody’s gonna tell me, not even God. Is God going to tell me, ‘You know what they’re talking about you?’”

Leave a comment