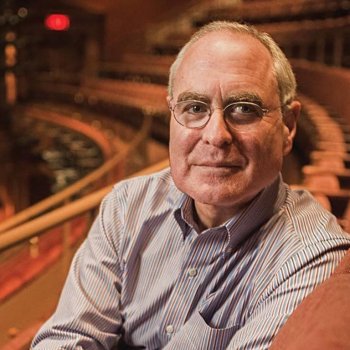

An Appreciation of Todd Haimes, Producing Artistic Director of Roundabout Theatre Company

Haines took a bankrupt theater company and built it up into one of the world's most respected not-for-profit theater companies, with a staff of 150 and an annual budget of $50 million.

Todd Haimes (1956 – 2023)

[avatar user=”Chip DeFFaa” size=”96″ align=”left”] Chip DeFFaa, Editor-at-Large[/avatar]

I’m sorry to note the passing of producer Todd Haimes, who’s lost his long battle with cancer. In his four decades heading the Roundabout Theatre Company, he’s made an extraordinary impact on New York theater. What a difference this one man made! He took a bankrupt theater company and built it up into one of the world’s most respected not-for-profit theater companies, with a staff of 150 and an annual budget of $50 million.

Roundabout–then a tiny off-Broadway theater company, renting a small theater in Chelsea–was on the ropes when Haimes assumed leadership, at the age of 26, in 1983. Just a few weeks after he joined Roundabout, the Board of Directors voted to dissolve the company; it was drowning in debts and they saw no way forward. (The theater then had debts of $2.5 million and an annual budget of about $2 million.) On that day–meeting with his Board after coming from his own mother’s funeral–he pleaded for more time. He got one board member to donate enough funds to keep the lights on for a few more weeks. (He said that the Board member felt sorry for him because it was the day of his mother’s funeral and it seemed too cruel to declare the theater company dead on the same day.) Haimes used his own personal credit card to pay some past-due company bills.

And he began experimenting–presenting some shows at earlier times to attract an after-work crowd, creating special promotions aimed at single and gay theatergoers. He worked hard to nurture new playwrights. And he was always open to new ideas, which I liked a lot.

When he said, in the late 1990’s, that he wanted to present Cabaret, but wished he had a seedy venue to fit the mood of the play, I wrote him to check out the Henry Miller’s Theatre, which was then dark and in a state of decay; it was definitely seedy, and could surely be obtained very cheaply. I still treasure the letter I received back from him, saying he doubted the derelict Henry Miller’s Theatre could work, but he’d check it out. He wound up falling in love with the theater. I was thrilled to be there when he opened Cabaret at that theater (renamed “The Kit Kat Club” to fit the show) in March of 1998; Cabaret was a hit there for about eight months; then it moved to a much larger space, Studio 54. That revival, which ran for nearly six years, brought a lot of money into Roundabout, and helped Haimes establish himself as a major player on Broadway. None of this was pre-planned, he noted; things just seemed to evolve naturally, organically. And while he became a major Broadway producer, he didn’t feel he had much in common with most Broadway producers he knew; he said his primary interest was in presenting good theater, not in making the maximum amount of money possible.

Roundabout eventually wound up controlling three Broadway theaters–taking over the Henry Miller’s Theatre (today the Stephen Sondheim Theatre); Studio 54; and the American Airlines Theatre (formerly the Selwyn Theatre) on 42nd Street. Roundabout also runs an Off-Broadway theater and an Off-Off Broadway black-box theater, to support emerging artists.

Roundabout, under Haimes’ leadership, was noted both for new works and for revivals of older shows with strikingly new elements (like this season’s gender-bending revival of 1776.) He was the first producer to try livestreaming a Broadway show (She Loves Me in 2016).

And somehow, besides producing lots of shows (and 11 Tony Awards), Haimes also found time to teach at Yale University and Brooklyn College. The biggest change he saw in theater in his career, he said, was the change in audience composition, with Broadway growing more and more reliant on tourists. He said it bothered him that nowadays, in his opinion, so many theater ticket buyers preferred to see crap so long as a star they knew from TV or film was heading the cast, than see a better play with better (but not necessarily famous) actors.

He liked to trace his own love of theater to being chosen while in grammar school in Manhattan to star as “Mary Poppins” in the school’s production of Mary Poppins. In a wig and a dress, he sang the songs he’d loved hearing Julie Andrews sing in the movie. And theater became his first interest for life.

A few years ago he said that he hoped to work until he was 70, but that contingency plans were in place should he die before then, noting, “My cancer is in remission right now. But cancer is in remission… until it’s not.”

He was 66.

Leave a comment