New York Choral Society and The Mannes Orchestra: For Those We’ve Loved

Thoughtful programming, an uneven performance, but artistic integrity intact with some splendid moments.

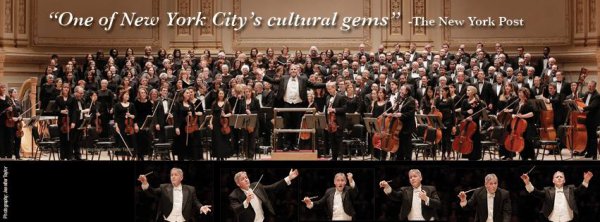

New York Choral Society and Orchestra and Music Director David Hayes (Photo courtesy of New York Choral Society)

[avatar user=”Jean Ballard Terepka” size=”96″ align=”left” ] Jean Ballard Terepka, Music Critic[/avatar] The New York Choral Society’s most recent concert, led by David Hayes, New York Choral Society’s Artistic Director, featuring the chorus, The Mannes Orchestra, the Young People’s Chorus of New York City, and two very fine soloists, was atypical. The program consisted of two parts. The first half consisted of John Adams’ On the Transmigration of Souls and the second, Paul Hindemith’s When Lilacs Last in the Door-yard Bloom’d.

The Hindemith was beautifully performed and the second half of the concert was successful. But the first half, the Adams, was not a success. It was not an abject failure – Hayes wouldn’t permit that – but the performance did not produce the kind of considered satisfaction that New York Choral Society concerts typically do. The reasons for this lay in the nature of Adams’ piece and in particular features of the performance itself.

In the immediate aftermath of 9/11, the chaos of grief felt uncontainable. The mourning for lives lost was coupled with such shocked confusion about the nature of the attacks that responses to the event were themselves confused, ranging from useful eloquence to rigid anti-intellectualism, and from careful emotional restraint to unfettered, sloppy sentimentalism. Creative artists – like Adams – called upon to create memorials immediately after the event operated in a charged and polarized cultural atmosphere; the vocabulary of response was still dense with first-hand, gritty memories of the September day’s details and artists were faced with difficult aesthetic, intellectual and even moral choices about which details to include in memorial pieces.

In spite of the enduring beauty of most of On the Transmigration of Souls – one of the best of hundreds of commissioned memorial responses to 9/11 all around the country – the inclusion of recordings of street and emergency sounds may prove to be expendable: in 2002, these recorded narrative elements might have seemed necessary for the completeness of the piece, but, over time, they’ve come to seem less and less necessary to the integrity of the work, and problematic to attentive audiences.

Twenty-first century audiences are accustomed to the integration of recorded material in music performances, but Transmigration asks listeners to make impossible decisions about the recorded material. Is its presence to be tended to, analyzed and parsed out as a way to make sense of 9/11 or of this music? Or is it to be ignored and blocked out, as, ultimately, we have to shut out awfulness when the sheer quantity of it threatens our sanity? If we strain to hear the recorded sounds, we lose some of our relationship with Adams’ music – surely not Adams’ intention – but if we strive to ignore it, then we find ourselves distracted, wondering what we’ve missed. When the music is choral – when the composers have committed to words as part of their created art – then the question of missed or lost text is doubly tough: words are meant to be heard and understood.

Hayes generally insists on clear enunciation from the singers he works with: in fact, this is one of the steady pleasures of the New York Choral Society. So the sections of Adams’ Transmigration in which the singers’ words couldn’t be understood – generally the opening and closing thirds of the work, when the recorded material figures more or less prominently – were frustrating and disconcerting. Fortunately, this group’s choral sound as Hayes has shaped it over the years is sufficiently coherent and clear so that the sound in and of itself is an effective instrument; the result, in this instance, is that though the words in these portions of the Transmigration were virtually unintelligible, the vocal sound contributed to the musical drama.

Interestingly, in this performance, the most successful portion of the piece was the most explicitly text-dependent: the lines Adams imported from the New York Times‘ enduringly moving “Portraits of Grief” provided material for the most beautiful music in Transmigration. Here, the chorus shone.

The success of this performance of Adams’ Transmigration was hindered by one additional element. The Mannes Orchestra – by definition a young group, not able to acquire over time a sense of itself as an organic whole – responded to Adams’ difficult, very fast and rhythmically dense writing not by any sloppiness or inaccuracy but by an inability to sustain any wide spectrum of volume: the orchestra, especially the strings, settled somewhere between mezzo forte and fortissimo through much of the piece, thereby often drowning out the sound of the chorus and exacerbating the problems inherent to much of the piece.

In spite of these major and complex problems, the raw emotion and the aesthetic rewards of even a flawed performance, such as this, of Adams’ Transmigration were fully felt by the audience; acknowledging the sheer cumulative power of the piece, the audience vigorously applauded the New York Choral Society, the Young People’s Chorus of New York and The Mannes Orchestra.

The second half of the concert – Hindemith’s remarkable When Lilacs Last in the Door-yard Bloom’d: A requiem “for those we love” – was wonderful. When Lilacs Last is a fascinating piece. Walt Whitman’s 1865 poetry calls together all America’s successes and failures, fears and optimisms; Hindemith takes Whitman’s nineteenth century vision as the shape for his twentieth century call to reclaim justice by honoring the ideals of America’s identity. Walt Whitman’s words have inspired composers as varied as Leonard Bernstein, Benjamin Britten, Ned Rorem, Frederick Delius, Ralph Vaughan Williams, Roger Sessions … and the evening’s John Adams precisely because of the quality of their sound and their rhythm: not obedient to particular rhyme and scansion patterns, Whitman’s words elicit daring from composers, and the wonderful ones make wonderful music.

Hindemith sets words for both chorus and soloists. The chorus was at its best under Hayes’ exacting and exhilarating direction. The two soloists were marvelous.

Mezz-soprano Abigail Fischer’s rich, strong voice, capable of both wistful sweetness and sultry urgency, was well suited to the demands of the text: she was equally fine as Whitman’s persona, calling up nature’s – birds’ especially – songs of mourning and freedom and then, as a paradigm of America, singing the songs herself.

The baritone’s role in When Lilacs Last is larger than the mezzosoprano’s: he is the declamatory voice of both the “poet” and history itself. Lee Poulis’ powerful, expressive voice carried Whitman’s words from the stage to the farthest reaches of Carnegie’s high balconies; his passionate affection for both the meanings of Whitman’s words and their sounds was radiantly clear.

Throughout the Hindemith, chorus, orchestra and soloists were exceptionally well balanced: here, The Mannes Orchestra, though performing music neither more nor less difficult than Adams’, played with nuance and subtlety.

The Hindemith demands a good deal from its audience: Whitman’s text is a complex one, not susceptible of full comprehension in any one encounter. Hearing it set to music reveals its sensuality and its emotion: these are cardinal to its several meanings. The gift of Hindemith’s score is to illuminate these meanings without sacrificing others. Chorus and soloists alike, treating the text with respect by enunciating very clearly, contributed to this fine performance.

Before the concert “officially” began, Hayes came to the stage and spoke briefly to the audience. He discussed the commonalities of the two works and his reasons for choosing to perform them together. He noted that Adams and Hindemith-and-Whitman were writing not memorials or requiems in any traditional sense, but exhortations to continuation and futurity. He spoke especially about Adams’ desire to use Transmigration as a way to provide a “memory space” and about Hayes’ own desire to use the concert to further that same goal on a long range basis.

Hayes’ remarks were useful, insightful and inspiring: artists and audiences alike need art to make sense of tragedies and injustices and to continue forward with greater wisdom. That this concert was uneven in its success diminished neither the intelligence of the programming nor the New York Choral Society’s ability to retain the loyalty of its audience.

New York Choral Society and The Mannes Orchestra : For Those We’ve Loved (April 8, 2015)

Carnegie Hall, 881 Seventh Avenue at 57th Street, in Manhattan

For more information: visit http://www.nychoral.org or http://www.carnegiehall.org

Running time: two hours including one intermission

Leave a comment