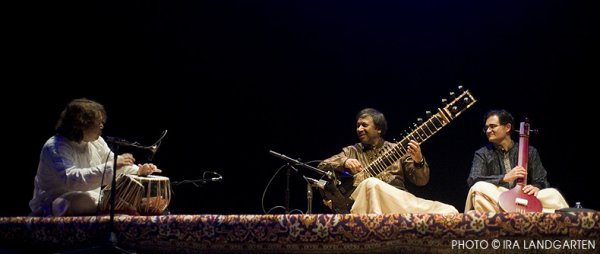

Ustad Shahid Parvez Khan: An Evening of Indian Music

Ancient ragas, present day engagement with timeless musical traditions and enduring spiritual rewards.

The audience was made up of several constituencies. There were Indians who knew the music intimately; there were fans and subscribers of the unique and dynamic World Music Institute whose programming both enriches New York City and recognizes the wealth of cultural heritages that make up the city; there were aging New Yorkers who never forgot Ravi Shankar’s legendary performances or George Harrison and the Beatles’ “discovery” of the sitar in the mid-1960s; finally, there were Upper West Siders who make it a habit to regularly drop in on Symphony Space just as part of the project of living in the neighborhood. The reward of this April 10 concert was that the musicians’ performance constituted an invitation into a musical world that was exciting for all audience members, whether or not they were familiar with Indian music, and the whole audience responded with enthusiastic appreciation – and a standing ovation – at the end.

Shahid Parvez Khan comes from a long line – seven generations – of musicians and sitar masters. This fact is emphasized in both the musician’s own and the World Music Institute publicity materials. Shahid Parvez Khan’s ancestry is critically important for those who are well versed in both historical and contemporary Indian culture and music, but for those who know little about Indian music, it figures only as an interesting biographical fact. What is much more relevant to the listening experience is Shahid Parvez Khan’s assertion that “the Sitar and Self are identical entities,” a statement confirmed by the experience of simultaneously watching and listening to the sitar player as well as his colleagues.

The concert was divided into two parts separated by one fifteen minute intermission. The first part was one extended raga and the second, another raga with some smaller sections of others. (One of the few frustrations of some World Music Institute concerts and performances is the lack of a concert program. This omission leaves audience members scrambling to find out musicians’ names, their accurate spellings, and program details; it also denies audience members the ability to build a “library” of concert materials for reference over the years. A concert program would not need to be elaborate [or expensive] – a single sheet would do – to provide useful information.) In both halves of the concert, the familiar raga structure created a trajectory of predictable experience within which to locate one’s listening. Even for those who know little about ragas, their architecture, as revealed in these musicians’ generous performance, became clear.

The raga opens almost incidentally. The sitar player seems to be “playing,” or “looking around” for just the right note combinations; for the listener, it feels like eavesdropping on the sitarist’s musings. And then, without any announcement, the music, it becomes clear, has formally begun. The sitarist plays (seemingly alone, although the tanpura player provides a subtle droning undertone) a particular series of notes, exploring their relationships according to what turn out to be ancient patterns and formulations. At a certain point, the tabla player joins in, adding percussive elements that begin as ancillary support and then evolve into equal partnership with the sitar.

Tabla and sitar then engage in conversation – dialog and dance – that varies in volume, tone and intensity before the tabla is given an extended moment of its own, something like a solo, until the two instruments come together again for further music-making until the particular tune or note-sequence has exhausted itself and the raga comes to an end.

Ustad Shahid Parvez Khan and Hindole Majumdar are gifted artists. In their hands, the ancient raga becomes not merely new and fresh, but alive … an unanchored, intangible but powerful entity on its own. The vibrantly living quality of the music emerges from the artistic notion of the identity, the oneness of self and instrument, and the resulting organic sound.

Shahid Parvez Khan’s virtuosity is stunning: he made notes, once launched from his hands and his instrument, behave differently in the air according to how he shook the sitar in his lap. Each individual note had its own trajectory, like sports-and-physics video visualizations of baseballs’ travels from pitcher to batter and then from bat to ground or sky. Different notes – the core raga notes whose relationships are being explored – sail out into the listeners’ air with almost infinite constellations of audible overlaps and undercurrents embarking on their own processions through space, even as new note arcs are being launched right behind them, creating countless complex chords of sound. According to the sitarist’s speed and volume, the musical sounds exist in the space between musician and listener with more or less intensity or urgency; the sitarist can make this multi-layered music sound liquid or metallic, pastoral or urban, leisurely or raced.

The tabla, too, makes wide varieties of sounds: some are self-contained and flat, some sing and some shimmer. Separately and together, the instruments make many more musical sounds than one might imagine single instruments could.

These artists treat the music they make not as something they have created, but as something they’ve discovered, come upon; their relationship with the music, no matter how skillfully they control the originating instruments, is one of privileged engagement.

In the hands of musicians as accomplished and masterful as these, these ragas themselves are living players in the relationships among the musicians and between the musicians and the audience. Engagement and invitation constitute the core of these relationships. The centuries old ragas become living participants in current experiences: creativity and tradition coexist, as they have for hundreds of years, in the present moment.

The musicians’ identification of themselves with their instruments and then with the music itself becomes an invitation to the audience: it is akin to an invitation to meditation or contemplation in the sense that the thorny preoccupations of daily projects can be laid aside and the ego of personal worries temporarily released in order to live in the music. But it is not a meditation of emptiness. It is, instead, an immersion in abstract fullness, a physical experience of rhythm and sound.

Listening to this music, it’s impossible to not sway, nod, tap and breathe with it: resistance to this physical participation is as foolish as trying to elaborate on one’s worry lists while listening. The surrender is lovely. The predictable trajectory of the raga has the feel of a wordless narrative; the time-out-of-time quality of folk tales applies. The end of the raga is not so much a guaranteed happy ending as the promise that one’s return to normal daily life will be accompanied by a feeling of refreshment and, even, delight.

In the raga, the invitation to enter the music is not to relax into soothing placidity but to enter into the physiological and aesthetic feel of psychological experience: the music is a vocabulary that combines body, soul and psyche with the making and receiving of art. Moods range from quiet to wild, acquiescent to explosive, wait to ecstasy. Within the arc of the raga, Ustad Shahid Parvez Khan and Hindole Majumdar separately and together engaged in short and extended improvisatory passages, entirely marvelous in the freedom of their exploration, entire stories on their own, before the satisfied return to the raga … marked by musicians’ smiles and visceral audience grunts and chest-shouts of gratification. In Western terms, the improbable analogy that best describes these musicians’ astonishing music is a combination of sophisticated jazz and symphonic Mahler.

Miking the tabla and the sitar enables the music to be audible in big performance spaces but these artists made it entirely intimate. Each ancient raga was fresh; the musicians’ seamless communication among themselves and the evident warmth of their completely non-verbal communication with the audience made the evening feel precious.

At the end of the concert, Indians who clearly knew the music well were beaming with appreciative pleasure. Audience members who knew little about the musicians, the instruments or the music were thrilled at what they experienced and learned … about their own capacity to listen, to say yes to spiritual and artistic invitations, and to receive the unexpected gifts of a timeless musical tradition.

Ustad Shahid Parvez Khan (April 10, 2015)

World Music Institute

Peter Norton Symphony Space, 2537 Broadway at 95th Street, in Manhattan

For more information, visit http://www.shahidparvezkhan.com, http://www.worldmusicinstitute.org, or http://www.symphonyspace.org

Running time: 90 minutes including one intermission

Leave a comment