Parade

In telling Leo Frank's heartrending story, a revived Broadway musical leaves too much of the past behind.

Micaela Diamond and Ben Platt as Lucille and Leo Frank in a scene from the revival of “Parade” at the Bernard B. Jacobs Theatre (Photo credit: Joan Marcus)

In our digital age it’s easy to find agonizing images of Leo Frank’s 1915 lynching in Marietta, Georgia, his face blindfolded; limbs bound; and neck snapped back. Gathered around the legs of the dangling corpse are a group of hollow-eyed, after-the-fact spectators whose chilling gazes suggest no sympathy for the Jewish pencil factory manager who had moved from Brooklyn to Atlanta hoping to build a life. Leo Frank’s actual murderers, many of them local luminaries, had long ago left the scene of the crime, though some of this camera-shy pack soon reconvened in a hooded, cross-burning ceremony that reignited the Ku Klux Klan atop Georgia’s Stone Mountain, a natural wonder turned future site of the world’s largest Confederate monument.

Any artist attempting to retell Leo Frank’s story risks buckling under the weight of this history, but Jason Robert Brown, the composer of the musical Parade, has taken on the added burden of spinning pain into melody. That Brown occasionally succeeds stems from estimable creativity, which, unfortunately, still cannot overcome the popular expectations of a Broadway show. Now in revival at the Bernard B. Jacobs Theatre, Parade cursorily focuses on what led to Leo Frank’s extralegal execution for the killing of a 13-year-old white girl, Mary Phagan (Erin Rose Doyle), who worked at the pencil factory.

Erin Rose Doyle as Mary Phagan and Jake Pederson as newsboy Frankie Epps in a scene from the revival of “Parade” at the Bernard B. Jacobs Theatre (Photo credit: Joan Marcus)

While Brown’s tunefully varied score strives to historically situate the bigoted nightmare we’re witnessing within the cultural context of the South’s fabricated sense of nobility and victimhood, an offensive postbellum myth known as The Lost Cause, Alfred Uhry’s reductive book ham-fistedly narrows our attention, transitioning from a corrupt law-and-order procedural in the first act to a preposterously scripted search for the truth after the intermission. Although Dane Laffrey’s unremarkably fungible from-courthouse-to-prison-to-gallows set overbrims with historical figures, most of them exist on a character believability spectrum somewhere between My Cousin Vinny and Driving Miss Daisy (also written by Uhry). If not for Sven Ortel’s rear-wall historical projections of these real people, an audience might suspect at least a few of them were invented out of whole cloth.

To be clear, the book’s shortcomings are less an issue of dramatic license than dramatic inertia, with Uhry settling for paper-thin characterizations when the past offers the possibility of so much more. Even the depiction of the relationship between Leo Frank (Ben Platt) and his Georgia born-and-raised wife Lucille (Micaela Diamond), the offspring of a wealthy Jewish family, suffers from Uhry’s slack approach, as the latter’s brutally undermined faith in assimilation is not nearly the subject of marital discussion one might expect. As for the couple’s emotional connection, Uhry lets Brown do the heavy lifting through heart-and-soul-bearing numbers like “You Don’t Know This Man,” a defense of Leo’s integrity that Lucille sings solo to a scandal-mongering reporter (Jay Armstrong Johnson), and the generically romantic “All the Wasted Time” that Lucille and Leo quaver at each other when they ingenuously think better days are coming.

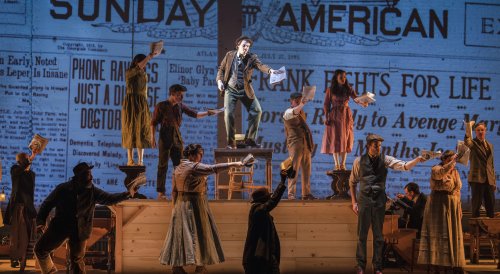

Jay Armstrong Johnson as reporter Britt Craig and company in a scene from the revival of “Parade” at the Bernard B. Jacobs Theatre (Photo credit: Joan Marcus)

While Platt and Diamond’s stunning voices are tremendously well-suited to the lusher parts of Brown’s score, that bizarrely freestanding beauty is often at uncomfortable odds with the horrific inevitability of Leo and Lucille’s story. It becomes especially problematic when director Michael Arden’s staging, thrown into sharp relief by lighting designer Heather Gilbert, leans into Platt and Diamond’s showstopping potential during one of their duets. As lengthy applause visibly overwhelms the actors, Parade feels completely severed from history.

That detachment is further reinforced by both Uhry and Brown’s broad treatment of Leo Frank’s persecutors, particularly the anti-Semitic newspaper publisher Tom Watson (Manoel Felciano) who sprayed his venomous rhetoric even more wildly after the Georgia governor John Slaton (Sean Allan Krill) commuted Leo Frank’s death sentence to life in prison, a compassionate decision hate ultimately wouldn’t allow. What neither Uhry nor Brown touch upon is the rising backlash that chipped away at the values of the New South and helped transform Watson, once a pro-Black suffrage, anti-lynching advocate, into a white supremacist. If Parade wants to enlighten audiences about current demagogic perils, as implied by the musical’s closing caption/warning, “It is still ongoing,” then Uhry and Brown missed a chance to take a hard look at the destructive nature of political opportunism.

Howard McGillin as Judge Roan, Danielle Lee Greaves as housekeeper Minnie McKnight and prosecuting attorney Paul Alexander Nolan in a scene from the revival of “Parade” at the Bernard B. Jacobs Theatre (Photo credit: Joan Marcus)

With the satirical “A Rumblin’ and a Rollin’,” Brown kicks off the second act proving some capacity for historical complexity. In the song, two Black servants (Courtnee Carter and Douglas Lyons) from the governor’s mansion ridicule Northern outrage about Leo Frank’s conviction and potential hanging when “there’s a Black man swingin’ in every tree.” On another matter of race, however, Parade has less to say than it should, underplaying the extraordinary fact that the prosecution’s star witness at Leo Frank’s trial was Jim Conley (Alex Joseph Grayson), a Black janitor from the pencil factory. As one might instinctively guess, Black testimony against non-Black defendants wasn’t usually the cornerstone of capital convictions in the Jim Crow South.

Rather than narratively contend with the historically conspicuous, Uhry instead favors the outlandishly imaginative, teaming up Lucille and Governor Slaton to prove her husband’s innocence, as if they were characters in a schlocky detective novel. Though, to be fair, after stretching our credulity, Uhry does make good use of verifiable history by referencing what Slaton really said when he commuted Leo Frank’s sentence: “Two thousand years ago, another governor washed his hands and turned a Jew over to the mob…If today another Jew went to his grave because I failed to do my duty, I would all my life find his blood on my hands.” It’s too bad Uhry didn’t turn to the archives more often.

Parade (through August 6, 2023)

Bernard B. Jacobs Theatre, 242 West 45th Street, in Manhattan

For tickets, call 212-239-6200 or visit http://www.paradebroadway.com

Running time: two hours and 30 minutes including one intermission

Leave a comment