Broadbend, Arkansas

World premiere of exquisite chamber opera masquerading as a musical is both moving and melodic with music as American as Aaron Copland and a story as vital as Harper Lee.

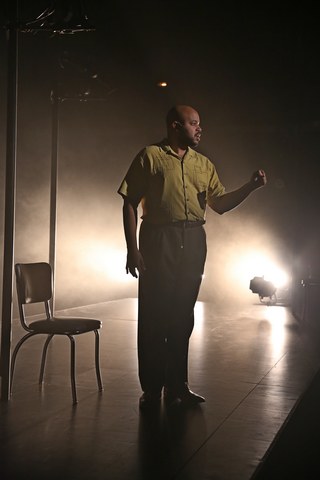

Justin Cunningham in a scene from “Just One Q,” Act I of “Broadbend, Arkansas” (Photo credit: Carol Rosegg)

[avatar user=”Victor Gluck” size=”96″ align=”left”] Victor Gluck, Editor-in-Chief[/avatar]

Broadbend, Arkansas is an instant classic. Although billed as a musical, it is really a chamber opera. The beautiful melodic music by Ted Shen is as American as Aaron Copland with influences of a great many other composers (Samuel Barber, Richard Rodgers, Leonard Bernstein, etc.). It is also unusual in that the first act libretto, “Just One Q,” sung by baritone Justin Cunningham, is written by Ellen Fitzhugh (Grind, Diamonds, Herringbone, Paper Moon) while Act II called “Ruby” (sung by soprano Danyel Fulton) is by Harrison David Rivers, a name not well known in New York.

Produced by Transport Group in association with The Public Theater and directed with precision, clarity and simplicity by Transport Group’s artistic director Jack Cummings III, this story of three generations of an African American family grappling with of racism, violence and inequality in the South is as moving and trenchant as a story by Harper Lee. Each act is a monodrama exquisitely acted, sung and directed for a very discerning audience. While there is dialogue in both halves of these personal stories, the extraordinary music makes it feel sung through.

Justin Cunningham in a scene from “Just One Q,” Act I of “Broadbend, Arkansas” (Photo credit: Carol Rosegg)

Both acts have one African American actor who performs as both narrator and singer, 36-years-old Benny Tate in 1961, and then later his daughter Ruby Tate, aged 30-years-old in 1988. The first act includes three chairs while the second has just a bare stage except for five poles with lights in the minimalist design, which allows the viewer’s imagination to fill in the rest. In Act I, “Just One Q,” we meet Benny Tate (sung by Cunningham), an orderly at the Broadbend Nursinghome, Arkansas, in 1961, a time of the Civil Rights movement in the Deep South. He is refereeing a contentious scrabble game between two white women, his boss Julynne and Bertha, a resident of four months.

However, the real problem isn’t the game with its one “Q” but the fact that both women had been married to the same man, Cotton Green, a womanizer who took up with Julynne after Bertha left him and took their 11 children with her to California. Benny is to drive Bertha to her daughter in Memphis, but having become fascinated by the Freedom Riders, he has gotten Julynne to agree to his taking a few days off to follow their bus to Alabama while she cares for his three-year-old twin daughters, Ruby and Sam. Benny is psyched by meeting the Freedom Riders and their cause but witnesses much racism, bigotry and violence from white supremacists that they meet at stops along the way. Ultimately, he is caught up in one of the riots that is provoked by racists who resent these Northerners who they feel are invading their land.

In the opening sequence, Cunningham amusingly plays all three characters by using the three chairs and changing his voice. Once he joins the Freedom Riders caravan, he conveys his sense of exhilaration as he feels that change is coming and he doesn’t mind finally entering the fray himself even though he knows he has his two daughters waiting for him at home. Cunningham is both wry and poignant as he describes things as they have always been and his accommodation with them.

Danyel Fulton in a scene from “Ruby,” Act II of of “Broadbend, Arkansas” (Photo credit: Carol Rosegg)

When we meet his daughter Ruby 27 years later, she is bitter and angry, yet compassionate and aware. She is the mother of Ben, a 15-year-old boy named after her father, who has been framed by the police and is in the hospital having been beaten for resisting arrest. Unable to deal with the situation after seeing his injuries, she has driven to the cemetery and speaks to the grave of the only mother she has ever known, Julynne, who has died the year before. She bemoans the life she has lived in Broadbend and the racism that she encountered growing up as only one of five black students in the white elementary school. She envies her sister Sam, a fighter from the beginning, who left town to go to college and never came back. Having a mother who was in the local insane asylum and a father who never returned from his trip south made life difficult for Ruby with the other girls in her classes.

Danyel Fulton in a scene from “Ruby,” Act II of “Broadbend, Arkansas” (Photo credit: Carol Rosegg)

Ruby remembers Julynne’s saying that “God never gave us more than we can handle,” and only has good memories of Julynne’s upbringing though she could not take away the bigotry that Ruby experienced everywhere else. She recalls Julynne’s finally telling her father’s story and what really happened to him down south, and she compares his experiences to what her son has been subjected to. Standing by her father’s grave and trying to figure out how to explain the world to her son, she has a vision of her father who apologizes for having had so little time for her and gives her some good advice. After hearing from her father, Ruby realizes that it is her job to “get back on the bus” (in the parlance of the Freedom Riders) and move forward with her son.

As Ruby, Fulton runs a gamut of emotions as she relives her life, ponders her fears and plans for her future. She instantly creates the young woman who has only known privation and worries having become pregnant at age 15. She brings to life the other characters (her stepmother Julynne, her sister Sam, etc.) just as Cunningham does in the first half.

As the only singer in each half, Cunningham and Fulton are riveting as they tell us their stories which evolve naturally out of their situations. Although written by two different writers, the two halves work amazingly well. Ironically, Ben’s half is written by a woman, while Ruby’s half is written by a man. Shen’s magnificent score conducted by pianist Deborah Abramson is orchestrated by Michael Starobin for piano, violin, bass, reed and cello and resembles Barber’s justly famous Knoxville, Summer 1915. With the sound design of Walter Trarbach, the diction is crystal clear, not usually true in operas sung in English. While the stage has little or no scenery, Jen Schriever’s evocative lighting creates the mood and locale instead. Broadbend, Arkansas is a little masterpiece that should have a long life on the concert stage.

Broadbend, Arkansas (through November 23, 2019)

Transport Group in association with The Public Theater

The Duke at 42nd Street, 229 W. 42nd Street, in Manhattan

For tickets, 646-223-3010 or http://www.dukeon42.org

Running time: one hour and 45 minutes including one intermission

Leave a comment