Death of a Salesman

An Arthur Miller classic returns with both a new and old outlook.

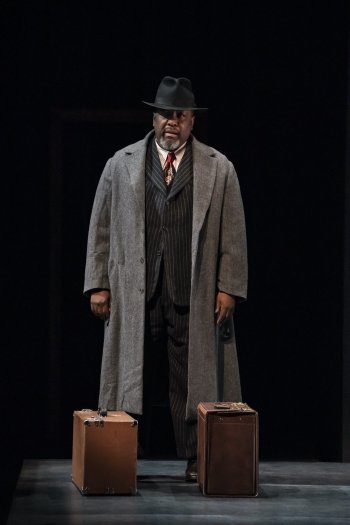

Wendell Pierce as Willy Loman in a scene from Arthur Miller’s “Death of a Salesman” at the Hudson Theatre (Photo credit: Joan Marcus)

If nothing else, the American Dream guarantees the right to hope, which is often a crushing privilege. That’s the stark paradox Arthur Miller explores in his classic 1949 tragedy Death of a Salesman through the now archetypal figure of Willy Loman, a past-his-prime patriarch whose invasively halcyon memories are buffers against the realization that a lifetime of hard work and positive thinking, what he considered to be the unassailable twin pillars of upward mobility, have betrayed him. It’s frequently argued that the play and, more specifically, Willy have lingered in the popular imagination due to the universality of the character’s common-man plight, a contention put to the test, and mostly affirmed, in its current London-to-Broadway revival that includes Black actors portraying the Loman family.

To be clear, the casting isn’t colorblind; it’s just casting, with director Miranda Cromwell delicately drawing out a different set of lived experiences from Miller’s almost untouched words. The play’s West-End co-director Marianne Elliott has not made the journey across the pond with its ongoing contributors, all of whom deserve kudos for the revelatory production, especially Wendell Pierce (Broke-ology, The Wire, Treme) as Willy and Sharon D. Clarke (Caroline, or Change) as Linda, his long-suffering wife. Though Pierce devastatingly pulls Willy apart in front of our eyes until all that’s left is his sense of failure, it’s Clarke who gives Willy’s downfall its saddest dimension, convincing the audience, beyond any doubt, that the very-flawed Willy is loved. If seeing previous productions of Death of a Salesman has inured you to Willy’s ultimate fate, this one should bring back the tears, and Clarke deserves a lot of credit for that difficult gift.

Sharon D. Clarke, Wendell Pierce and André De Shields in a scene from Arthur Miller’s “Death of a Salesman” at the Hudson Theatre (Photo credit: Joan Marcus)

While composer Femi Temowo interweaves music throughout the play to emphasize its reshaped racial dynamics, most poignantly by bracketing Miller’s script with an achingly beautiful rendition of the old spiritual “When the Trumpet Sounds,” largely what’s needed to make this adjustment was always there. As so often holds true, genius is simply a matter of pointing to the obvious, which the production repeatedly, elegantly, and believably does to one’s shortsighted amazement, and all without ever explicitly mentioning the Lomans’ race or racism. Sadly, that’s unnecessary because a postwar Black family is a shamefully natural fit for dramatizing the broken promises of American prosperity.

During the United States’ early ascendancy after World War II, when the relatively unscathed nation had huge economic advantages over its ravaged capitalist allies, severe inequality still reigned, particularly for Blacks subjected to Jim Crow in the South as well as that wicked system’s stealthier Northern variation. The latter is what afflicts Pierce’s Willy Loman as he struggles to hawk his nameless wares in far-flung parts of New England while pursuing financial security for his family in Brooklyn. Another layer of the character’s pain, it adds to the explanation for Willy’s mental deterioration and results in Pierce brilliantly embodying a lifetime of unspoken indignities in scenes like the one in which Willy learns that the boring white son (Stephen Stocking) of his boring white friend (Delaney Williams) has attained the type of success and respect that have eluded him and his own progeny. Even more gut-wrenching is what essentially amounts to the play’s coup de grâce, when Willy begs his brutally dismissive white boss (Blake DeLong) to take mercy on his aging body by letting him work a sales territory closer to home.

McKinley Becher III as Happy, Wendell Pierce as Willy and Kris Davis as Biff in a scene from Arthur Miller’s “Death of a Salesman” at the Hudson Theatre (Photo credit: Joan Marcus)

The sins of segregation also lend historical weight to the relationship between Willy and his two adult sons, Biff (Khris Davis) and Happy (McKinley Belcher III), in that we now comprehend the young men’s ineffectualness as a consequence of the past and everything it’s wrought. In particular, the older and favored Biff’s inability to “get started” becomes less a question of will than opportunity, with his father’s constant cajoling to follow him into business approaching something akin to cruelty. That Biff would rather live out his days as a Texas rancher–shunning the hypocrisies of the North at a time when millions of Black Southerners were desperately streaming towards them–could almost convince you that somebody has finally staged the production of Death of a Salesman that Miller always had in mind.

But there are still historical loose ends that prove it’s not. While in Willy’s reveries it’s easy to switch the younger, football-obsessed Biff’s preferred college from the University of Virginia to U.C.L.A (the first Black student wasn’t admitted to the former until 1950), there are other aspects of the play that aren’t so alterable. Most saliently, the production must simply elide the bitter and burgeoning practice of redlining to make the ending work.

Blake DeLong as Howard and Wendell Pierce as Willy in a scene from Arthur Miller’s “Death of a Salesman” at the Hudson Theatre (Photo credit: Joan Marcus)

Admittedly, it’s more than a quibble to note the sidestepping of such pervasively destructive bigotry. Still, if you know what’s being left out, perhaps it becomes possible to appreciate what’s there. That includes Anna Fleischle’s hauntingly deconstructed set, Jen Schriever’s expressionistic lighting, and an astonishing performance from the ethereally bedecked André De Shields (no sad fedora for Mr. De Shields), as Willy’s deceased brother Ben, whose ghostly visage of worldly affluence encourages Willy to keep selling, right into the grave.

Death of a Salesman (through January 15, 2023)

The Young Vic Theatre Production

Hudson Theatre, 141 West 44th Street, in Manhattan

For tickets, call 855-801-5876 or visit https://www.salesmanonbroadway.com

Running time: three hours and 10 minutes with one intermission

Leave a comment