The Kite Runner

The beloved novel by Khaled Hosseini has been adapted for the Broadway stage starring "The Blacklist"'s Amir Arison.

Amir Arison as Amir (center) in a scene from “The Kite Runner” at the Helen Hayes Theater (Photo credit: Joan Marcus)

[avatar user=”Victor Gluck” size=”96″ align=”left”] Victor Gluck, Editor-in-Chief[/avatar]

The Kite Runner, the beloved novel by Khaled Hosseini published in 2003, also turned into an acclaimed 2008 film, has been adapted for the stage by college professor Matthew Spangler and is now at Broadway’s Hayes Theater in a production by Giles Croft, former artistic director of the Nottingham Playhouse where he first staged the play in 2017. While the story covering 28 years of Afghan history remains compelling and involving, the play version has made several poor choices. Spangler uses a narrator just like the book but the first act stage version tells the story rather than dramatizes it. This is corrected in the second half which then tries to portray a great deal of events of the novel in the somewhat rushed second act.

The second problem is the performance of Amir Arison, star of nine seasons on NBC’s The Blacklist, and eight Off Broadway dramas, playing both The Kite Runner’s narrator and its protagonist Amir. As the narrator, Arison is totally impassive giving little weight to the tumultuous events he describes. He also plays Amir as both a child and as an adult. While he is unconvincing as the child Amir from ages 10 to 12, his mostly unemotional portrayal of the adult Amir undercuts the events he describes. Still more damaging to the story, the violence has been toned down greatly, changing the villainous Assef from a psychopath to just a bully, and leaving out the shocking events in the soccer stadium demonstrating Taliban justice. The story still creates its own spell but is greatly diminished from the strengths of the novel. Luckily most of the supporting cast is quite excellent which saves the play.

Amir Arison as Amir and Eric Sirakian as Hassan in a scene from “The Kite Runner” at the Hayes Theater (Photo credit: Joan Marcus)

The play begins in 2001 at the end of the story and then goes back to Amir’s childhood in 1973 in the gated community of the Wazir Akbar Khan district of Kabul. It also covers the events of the fall of Afghanistan’s monarchy with Daoud Khan’s bloodless coup, the Soviet Invasion, the exodus of those who could afford it to Pakistan and the United States, and the rise and brutality of the Taliban regime. Amir, an arrogant, entitled Pashtun boy from the ruling class, spends his days with Hassan, a Hazara, (treated as lower class) his own age who works as his valet, son of his father’s longtime servant Ali. Both are motherless boys and while Ali is a loving father, Baba, Amir’s father is distant and judgmental. Amir comes to resent the affection his father lavishes on Hassan.

Their favorite activity is kite flying in which strings covered with glass are used to cut your opponent’s string and bring it down, the winner being the last one flying. Hassan is the best “kite runner” in Kabul, able to know where a kite will land without following it. When Amir wins the local tournament, Hassan goes to find the last cut kite and is attacked by Assef, the local bully. Amir witnesses the attack but does nothing to stop it for fear of getting hurt himself. Unable to live with his betrayal or look at Hassan, he creates a situation in which Ali and Hassan leave his father’s employ.

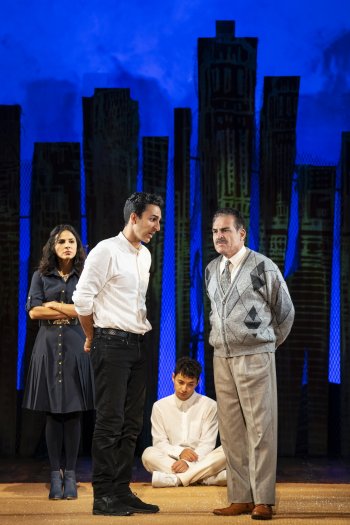

Azita Ghanizada as Soraya, Amir Arison as Amir, Eric Sirakian as Sohrab and Houshang Touzie as General Taheri in a scene from “The Kite Runner” at the Hayes Theater (Photo credit: Joan Marcus)

In the second act, Amir and his father flee the Soviet rule of Afghanistan and move to California where Baba, formerly a rich merchant, now works in a gas station. Amir finishes high school, starts college and wishes to become a writer. He marries Soraya, the daughter of former General Taheri, but they discover that they are unable to have a child. Just as they are considering adoption, Amir receives a phone call from his father’s best friend Rahim Khan, who was a confidant and friend to Amir: Hassan’s young son Sohrab is in the hands of the Taliban and Amir can redeem himself by returning to Kabul to save him.

Visually the play is a disappointment. Barney George’s minimal unit set has no atmosphere whatever and is not improved by the projections by William Simpson which also look cut-rate. It includes a wall of towers which seem to change from skyscrapers to a fence and back again. A strange fan-shaped curtain divided down the middle is used for some indoor scenes with equally strange projections on it. George’s costumes are quite bland but this may be accurate to the cultures depicted. It is Charles Balfour’s lighting that takes the prize in the second half when it is used instead of scenery to create ambiance and place. Salar Nader, the Afghan tabla virtuoso plays live music on stage through most of the play, while recorded music by Jonathan Girling is often heard at the same time. Philip D’Orléans is responsible for the very convincing fight direction in more than one scene.

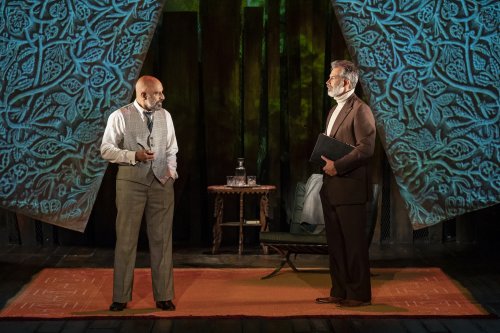

Faran Tahir as Baba and Dariush Kashani as Rahim Khan in a scene from “The Kite Runner” at the Hayes Theater (Photo credit: Joan Marcus)

Seven actors play two or more roles each but this is not a problem in following the characters. In the dual role of Hassan and Sohrab, Eric Sirakian is magnificent making the two roles entirely different but equally true to life. Unfortunately, Arison is so much taller than Sirakian, that when they are both playing children, he looks more like Hassan’s father than his contemporary. This is resolved when at age 38 he arrives to find Hassan’s son in the second half. Faran Tahir is equally impressive as Amir’s distant father who hides a shameful secret.

Although not given a great deal of stage time, Azita Ghanizada in the only female role is quite poignant as Amir’s love interest and later wife. Dariush Kashani is as moving as the compassionate and understanding Rahim Khan is in the novel. As the sadistic Assef, Amir Malaklou’s role has been so watered down as to make it only a cipher of what it is intended to be in Hosseini’s original. Houshang Touzie is fine as the austere General Taheri who lives by his own old-fashioned rules.

Faran Tahir, Beejan Land, Amir Arison, Danish Farooqui, Azita Ghanizada, Amir Malaklou and Houshang Touzie in a scene from “The Kite Runner” at the Hayes Theater (Photo credit: Joan Marcus)

Possibly the problem with Matthew Spangler’s adaptation is that he tried to get too much of the novel on stage without making enough changes to turn it into a play, while Croft’s production might have been more convincing had it used a second actor to play Amir as a child and more scenery to create Kabul as it once was. Amir Arison as Hosseini’s protagonist is better in the latter third of the play when he is required to show his reaction to the events around him, mainly dealing with the damaged Sohrab. Despite its flaws, the stage version of The Kite Runner does allow the original plot and theme to come though and is eventually absorbing and moving by the end.

The Kite Runner (through October 30, 2022)

Nottingham Playhouse and Liverpool Everyman & Playhouse Production

The Helen Hayes Theater, 240 W. 44th Street, in Manhattan

For tickets, call Telecharge at 212-239-6200 or visit http://www.thekiterunnerbroadway.com

Running time: two hours and 35 minutes

Leave a comment