True West

Ethan Hawke and Paul Dano co-star in the latest version of Sam Shepherd's explosive comedy-drama exploring myths of the American Dream, sibling rivalry and the Old West.

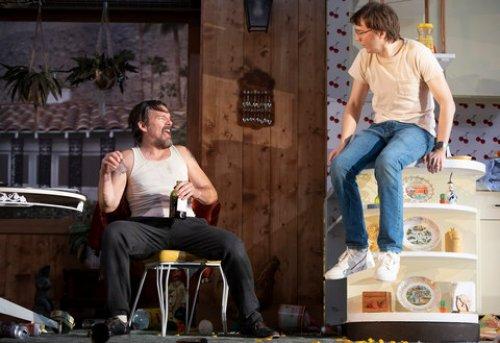

Ethan Hawke and Paul Dano in a scene from the Roundabout Theatre Company’s revival of Sam Shepard’s “True West” (Photo credit: Joan Marcus)

[avatar user=”David Kaufman” size=”96″ align=”left”] David Kaufman, Critic[/avatar]Having seen it at least four times before, I can say with certainty that Sam Shepard’s True West (1980) is a firm and solid play: a play to be pondered both while you’re watching it and afterwards, when you consider what you saw. But the current Roundabout production leaves more than just a little to be desired: it’s slow and plodding and contemplative, instead of explosive, which is what it’s designed to be.

Even though Ethan Hawke as Lee attempts to be volatile and fiery, his performance comes across as overwrought and false. Whether rocking on his feet or hurling objects all over the place, he’s always acting, instead of becoming Lee, the centrifugal character around which the play is built. Lee is the elder of two brothers, who, during the course of the play, essentially exchanges identities with his more docile and younger brother Austin. And, unfortunately, Paul Dano is as self-effacing and, in a word, “disappearing,” as Austin: there’s no heft or being left for the character.

Imagine what it was like to see–and review–a 1982 edition of the play featuring an unknown Chicago actor by the name of John Malkovich Off Broadway at the Cherry Lane Theater. Malkovich was certainly explosive, but also more natural and convincing as Lee. Then, imagine seeing Philip Seymour Hoffman and John C. Reilly as the two brothers on Broadway at the Circle in the Square Theater in 2000 when they exchanged the brothers’ roles on alternate nights. It was nothing less than mystical and magical.

No matter the cast, it’s always the same story: Austin is working on a Hollywood screenplay while staying at his mother’s house in Southern California and watering her many plants, when she goes on a tour of Alaska. Lee suddenly shows up after roaming in the Mojave Desert for several months and visiting with their “old man,” who lives there.

The sibling rivalry between the greasy slob of a man that is Lee, and the much neater Austin, is immediately apparent from their opening dialogue, which builds, as so much in the play does, even as it seems to constantly crescendo.

Ethan Hawke and Paul Dano in a scene from the Roundabout Theatre Company’s revival of Sam Shepard’s “True West” (Photo credit: Joan Marcus)

Lee is nothing less than menacing in a Pinteresque manneras he walks around in his black ratty trench coat, carrying a six-pack of beer, drinking from a flask when he isn’t drinking the beer or having a glass of whisky. (Lee can even be seen drinking before breakfast.) When Lee asks Austin if he can borrow his car, and Austin replies, ”You’re not borrowing my car! That’s all there is to it,” Lee threatens to “just take the damn thing.” The exchange is a compact demonstration of the brothers’ relationship with one another.

While describing himself as “a free agent,” Lee tells Austin that he “sticks out like a sore thumb.” Austin is just trying to go about his business of writing by candlelight on the patio table in the alcove off of the huge kitchen when his brother intrudes.

The realistic set design is by Mimi Lien who frames the stage with wrap-around neon lights that are illuminated between the scene changes as snatches of twangy, hillbilly music fill the auditorium. The evocative lighting is by Jane Cox, and the original music and sound design are by Bray Poor.

Lest it seem thus far from the description that True West is a two-character play, Austin is expecting a visit from his producer Saul (Gary Wilmes), and Lee correctly surmises that Austin doesn’t want him around for their meeting tomorrow. This only adds to Austin’s encroaching anxiety as delineated by Dano.

And then there’s “Mom” who comes home earlier than planned from Alaska because she “missed” her plants. But as soon as she arrives with three pieces of red luggage, you can tell she doesn’t even recognize her own home–as she says, “What happened in here?” The usually outspoken Marylouise Burke is perfectly baffled and dumbfounded as Mom.

Paul Dano and Ethan Hawke in a scene from the Roundabout Theatre Company’s revival of Sam Shepard’s “True West” (Photo credit: Joan Marcus)

During the course of the play, her two sons have basically destroyed her home, with litter and mess everywhere. And keep your eye on the many plants in front of the giant picture window which progressively die during the scene changes, since Austin fails in his one task, which was to water them. He fails in another as well, since Saul eventually decides to do a movie based on an idea Lee has even if Austin has to do the actual writing.

This is yet another manifestation of the many ways Lee and Austin exchange personalities if not identities. Lee even says to Austin near the end of the first Act, “I always wondered what’d be like to be you.” By the third scene in Act II, Lee is sitting at the table using the single-finger method to plunk something out on the typewriter, while Austin is drunk and sprawled out on the kitchen counter. And if Lee earlier steals televisions and other appliances from neighboring homes, Austin has now taken at least eight toasters from other’s homes which now clutter the set.

James Macdonald has directed the production with a realistic bent appropriate to the play–and the set. But in the end, one wishes Macdonald had found a way to make Hawke and Dano’s performances less rigid and more natural.

True West (through March 17, 2019)

Roundabout Theatre Company

American Airlines Theatre, 227 West 42nd Street, in Manhattan

For tickets, call 212-719-1300 or visit http://www.roundabouttheatre.org.

Running time: two hours and 20 minutes including one intermission

Leave a comment