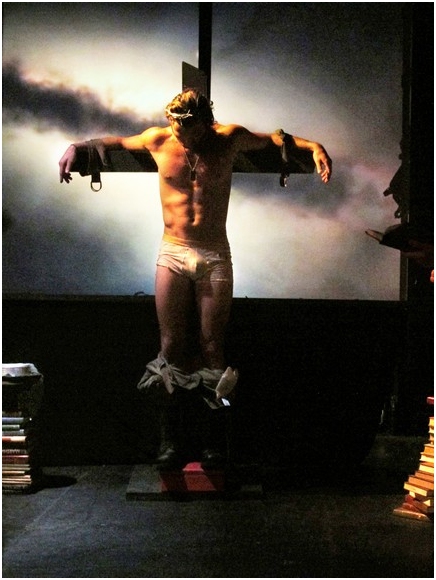

Culture Shock: 1911-1922

Rafael De Mussa, Wes Hager, Josh Wolonick,

Will Hardyman and Wilton Yeung in a scene

from Ithaka by Gottfried Benn

(Photo credit: Richard Termine)

Every so often an artistic style comes along that is irreducibly strange, typically arising when a new philosophical idea exerts an influence out of proportion to its ultimate worth.

For example, if we were to decide that our everyday world is actually teeming with invisible spirits, both benign and malevolent, we might get the early 16th Century monsters of Bosch and Grünewald. If we decide that Greek Tragedy was originally given out as monotonous chanting, we might get the music of the late 16th Century Florentine Camerata. If we decide that the purpose of art is to neutralize intellection so as to allow spontaneous enlightenment, we get the chance-based works of John Cage.

Regardless of the power of the individual works produced, these peculiar styles seldom have staying power: Bosch and his school had no successors; the dull efforts of the Camerata evolved within a few years into the much livelier song-and-dance spectacles we now call Baroque Opera; and Cage’s earlier and later works get more play nowadays than his chance pieces.

In theater, Expressionism is such a style. It arose in the late 19th century, taking its impetus from the then-new idea that people are driven by passions of which we are not consciously aware. Brought to first fruition by Strindberg, it attempted to reveal the subconscious to show the inchoate emotional subtext of ordinary existence bleeding through to the surface, disrupting and even destroying orderly narrative. Attempts were made to imitate “the logic of dreams”…until it was realized that dreams are not actually compelling unless you yourself are the dreamer. (Surrealism reclaimed dreams by holding them up as a funfair mirror of reality, but that too was not a sustainable style.)

This movement was embraced with particular fervency in Germany, and many of these experimental dramas are still in print. When reading them, however, it’s often hard to get a sense of how they played. The only example that is still performed with any regularity is Schoenberg’s 1909 opera Erwartung (Expectation), in which a deranged woman slowly realizes that she has murdered her lover. The best reference for what they looked like is the 1920 film The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. Everything there is deliberately anti-naturalistic, from the whiteface makeup to “buildings” which are obviously stage sets, and even those are twisted and distorted. Given all this, the opportunity to see a good handful of diverse one-acts from this period is welcome.

Wes Hager in a scene from Sancta

Susanna by August Stramm

(Photo credit: Line Krogh)

Dramaturg Rafael De Mussa has made an excellent selection:

* Sancta Susanna, by August Stramm (1911). This is best known today as an opera (1920, music by Paul Hindemith). It takes place in a convent, and the title character is a nun psycho-sexually obsessed with the image of the crucified Christ.

* The Guardian of the Tomb, by Franz Kafka (1916). In this black comedy, set in a world like that of Kafka’s later novel The Castle, the faithful servant who has guarded the royal tomb for many decades discloses that his real task has been the nightly struggle to keep the ghosts of the tomb from escaping and invading the palace.

* The Transfiguration, by Ernst Toller (1918). In this scene (excerpted from the full-length play), an unruly crowd ripe for insurrection is addressed in turn by a priest, an academic philosopher, and an anarchist, then finally won over by a socialist. (He also gets the girl.)

* Ithaka, by Gottfried Benn (1914). A university professor is confronted by proto-Fascist students, who first get the better of the argument and then murder him: “Our blood cries out for the heavens and the earth, and not for cells and invertebrates.” (Benn was indeed an early supporter of Hitler, but turned away from the Nazis in 1934; his work was subsequently denounced.)

* Crucifixion, by Lothar Schreyer (1920). Narrative disappears, as “Mother,” “Man,” and “Mistress” recite poetic fragments evoking the overthrow and resurrection of mankind.

For the record, only the first and last pieces here feature the continuous extremity we think of as central to Expressionism, but it’s not really important. What matters is that as a collection this is an excellent and well-balanced cross-section of the period.

Alas, although dramaturg De Mussa has done well, he has not done nearly as well as either director or actor, and the production fails the material badly at almost every turn.

The framing device is that we are in a bunker or a trench, and the plays are being presented by five soldiers (De Mussa, Wes Hager, Will Hardyman, Wilton Yeung, Josh Wolonick) and a nurse (Joyce Laoagan), as if whiling away the time between barrages, and in a semi-improvised fashion. This is a good idea, and provides a nice unity to the evening. The scenic design (Joseph Kremer) and lighting design (Daniel B. Barbee) supported this well, too. There were also projections and pre-recorded music tracks, which I assume should be credited to multimedia programmer Aristides F. Li.

However, often when the soldier-characters ‘read’ their lines (from books strewn about the space), their hesitations were indistinguishable from actual cold reading, and the narrative just disappeared. It was often unclear who was playing what part, or even whether the characters the ‘soldiers’ impersonated were men or women, which made certain scenes very difficult to follow. If I hadn’t known the story of Sancta Susanna in advance, I’m not sure I could have understood any of it. The Kafka piece really is a comedy, but the director seemed not to realize it.

The most conventional pieces (by Toller and Benn) fared best, though even they often suffered from poor enunciation and a lack of specificity by the cast. The only exception is Wilton Yeung who stood out in every scene as always intelligible and in character.

Worst off was Crucifixion, which went almost entirely for nought. This is actually a dance piece (or at least a movement piece) for which Schreyer went so far as to invent his own notation. To have the actors simply stand and intone phrases such as “Body, my flesh vessel. Clear fire pour the star,” while tearing up old books, made hardly any impression at all.

There was one bright spot in all of this—and it was a very bright spot. The projections, mostly from interwar or W.W. I newsreels, were often good but usually too short—it was impossible not to notice them looping over and over again. The music, during which interludes the action stopped, had a similar problem, using the same section from Gyorgy Ligeti’s Atmospheres at least three times, plus bits of his Requiem (familiar from its use by Kubrick in 2001). A recurring bit of Gustav Holst’s The Planets also wore out its welcome.

But then, between Ithaka and Crucifixion, we got nearly the whole slow movement of Bartok’s Music for Strings, Percussion, and Celeste, not just thirty seconds but a full five minutes (of a seven minute piece); and the film progressed with only a little looping, from soldiers before battle, to medical footage showing neurological disorders, to dead bodies being laid out for transport or burial. This was quite brilliantly done, and even moving. I’m not sure whom to credit for this (Li? De Mussa?), but hats off to them.

That five minutes wasn’t enough to make up for the rest, unfortunately. In sum: a great concept by the dramaturg, but very ill-served by the director.

Culture Shock: 1911-1922 (through September 21, 2014)

Horizon Theatre Rep at Access Theater, 380 Broadway, Manhattan

For tickets, call 212-868-4444 or visit http://www.SmartTix.com

Running time: 105 minutes with no intermission

Leave a comment