“Daddy”

From the author of “Slave Play,” another startling story of race, identity, sex and possession set among the poor artists and the very rich of Bel Air.

Ronald Peet and Charlayne Woodard in a scene from Jeremy O. Harris’ “Daddy,” a co-production of The New Group and Vineyard Theatre (Photo credit: Monique Carboni)

[avatar user=”Victor Gluck” size=”96″ align=”left” ] Victor Gluck, Editor-in-Chief[/avatar]Jeremy O. Harris’ “Daddy” has a good deal in common with his breakout play and New York debut last fall with Slave Play. Both plays deal with potentially abusive black-white relationships, problems with intimacy, unequal relationships, and childhood guilt. Each play is in three parts, with the third part veering into surrealism, and characters are often pressed to reveal their inner thoughts. And both plays, if not shocking, are startling in their pushing the envelope in new directions. However, while in Slave Play there was simulated sex, in “Daddy” there is a good deal of full frontal nudity of very attractive male bodies. Under Danya Taymor’s animated and spirited direction, the superb cast is led by Tony Award winner Alan Cumming and two time Obie Award winner Charlayne Woodard.

The title “Daddy” works on several levels. Franklin, a young black artist recently moved to Los Angeles, has met Andre, a fabulously wealthy white art collector thirty years his elder, vaguely European, at a gallery opening and been invited back to his mansion in Bel Air. They are immediately attracted to each other and become lovers, with Franklin moving into Andre’s house. Andre becomes Franklin’s “sugar-daddy,” giving him a studio, and wining and dining his friends Max and Bellamy on sushi and cocaine. But Franklin has another issue: he has never known his father who abandoned his mother before he was born, and she took her revenge later on by not letting him see his son. Franklin has only seen him from the back of his head when his mother turned him away. And if we don’t get it, Andre takes to singing George Michael’s “Father Figure.”

Alan Cumming, Kahyun Kim and Tommy Dorfman in a scene from Jeremy O. Harris’ “Daddy,” a co-production of The New Group and Vineyard Theatre (Photo credit: Monique Carboni)

Franklin’s vapid Los Angeles BFF’s, Max, an out-of-work actor, and Bellamy, a fashionista looking for her own sugar daddy, envy Franklin his luck though seeming to do nothing to further their own careers. Franklin prepares for his first show which Alessia, his gallerist, insists could prove him to be the Next Big Thing the art world is waiting for. His specialty is miniature black dolls which may represent him. In the second act, his mother Zora arrives to see his show – but also to save him from himself as she thinks Andre is a bad influence on him. A Bible quoting woman, Zora does not seem to mind Franklin’s homosexuality but feels that Andre’s money has bought his soul. She also sees Franklin’s art as a reproduction of the “coon baby” dolls she saw in stores as a child.

On one level the play is about race: a wealthy white collector attempts to appropriate a handsome young black man, a talented artist and add him to his collection. However, like Slave Play, “Daddy” operates by working out a theory. When Franklin and Andre have just met, Franklin tells him that “Art loses its worth the minute it can be bought. It becomes worthless once it is owned.” The play seems to prove instead that a love which attempts to completely possess someone destroys both people in the process.

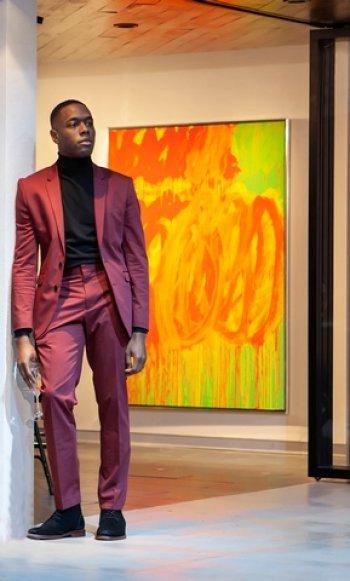

Ronald Peet in a scene from Jeremy O. Harris’ “Daddy,” a co-production of The New Group and Vineyard Theatre (Photo credit: Monique Carboni)

Halfway though the play once his mother has been convinced to stay in Andre’s house, Franklin begins to regress to his childhood, sucking his thumb like he did as an adolescent. In his encounters with his mother, Franklin takes on an earlier childhood relationship. To some extent, the play is extremely Oedipal in its depiction of fathers and sons, mothers and children. Andre asks Franklin to call him “Daddy,” Franklin responds by asking him to call him “Son.” Throughout the play, a three-woman gospel choir floats through the play, according to the script “Franklin’s forgotten heart and soul,” but only Franklin appears to be able to see them. And like Slave Play’s third part, things become very surreal in the third act but the ending doesn’t quite end the story we have been watching. A gimmick with an unanswered phone goes unexplained for too long.

Under Taymor’s direction, the cast is better than their roles as the characters are somewhat underwritten. Considering the play with two intermissions is just under three hours, we don’t learn much about them. As Andre, the enigmatic collector whose source of income we never discover, Cumming is charming, suave and elegant. He has great aplomb in his nude swimming scenes as a man in his 50’s. As Franklin’s mother Zora, Woodard is chic and graceful, a church lady who can also tell it like it is and is not easily shocked by what she sees going on in Andre’s house. In the complex role of Franklin, rising actor Ronald Peet (The Meyerowitz Stories (New and Selected), First Reformed, and Netflix’s upcoming series, The I-Land) makes him a real person but the play does not give him enough room in which to develop, only regress. Often seen swimming or lolling on the terrace in the nude, he reveals the sort of enviable physique that makes him a believable object of Andre’s desire.

Tommy Dorfman, Kahyun Kim, Alan Cumming, Onyie Nwachukwu, Denise Manning, Ronald Peet, Charlayne Woodard and Carrie Compere in a scene from Jeremy O. Harris’ “Daddy,” a co-production of The New Group and Vineyard Theatre (Photo credit: Monique Carboni)

Tommy Dorfman’s Max, the out-of-work actor, and Kahyun Kim’s Bellamy, the fashionista in search of someone to bankroll her, are hilarious in their superficiality and materialism, a put-down of LA hanger-ons. As the gallery owner Alessia who takes a chance on Franklin, Hari Nef is also a figure of fun as a parody of the commercial art world where success is measured only in dollars. Carrie Compere, Denise Manning and Onyie Nwachukwu are fine singers as the Gospel Choir, although their role is not entirely made clear in the play.

“Daddy” is worth seeing for its production design alone. Taking the script’s suggestion of David Hockney’s “Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures),” 1971, Matt Saunders’ magnificent infinity pool (which splashes the first two rows but towels are provided) and terrace of a Bel Air mansion is exactly right, a sort of all white Le Corbusier or Mies van der Rohe villa, letting us know that it is Southern California as soon as we see it. The off-stage house is conceived as so big that there is a running gag that Andre cannot find the kitchen each time he goes in from the terrace to get his guests something.

Kahyun Kim and Tommy Dorfman in a scene from Jeremy O. Harris’ “Daddy,” a co-production of The New Group and Vineyard Theatre (Photo credit: Monique Carboni)

The play of colored lights by designer Isabella Byrd is as much a work of art as is the set, inevitably changing the mood and the time of day. Montana Levi Blanco’s chic and colorful designer clothes look like they may have cost as much as the set. Other members of the team who contributed greatly to the overall effect are doll designer Tschabalala Self, movement director Darrell Grand Moultrie and intimacy and fight director Claire Warden. Though there is no credit for the artwork, what we see are excellent reproductions of Franz Kline and Kara Walker, among others. We are told Andre owns a Calder, a Lichtenstein, an O’Keefe, an Arbus, two Cindy Shermans, and a room full of Basquiats, but we are not invited to see them, though the mention does add to the ambiance of the play.

Jeremy O. Harris’ “Daddy” (subtitled “a melodrama”) is the work of a unique voice, a little self-indulgent in its length, and a little underwritten in its characterizations. It attempts to shock with its use of nudity and sadomasochistic sex, but nothing we have not seen before. The play’s message is not entirely clear but the play is provocative nevertheless. It is a work for the mature playgoer who wants to see a new direction that our theater is heading.

“Daddy, ” A Melodrama (through March 31, 2019)

The New Group and Vineyard Theatre

The Pershing Square Signature Center

Romulus Linney Courtyard Theatre, 480 W. 42nd Street, in New York

For tickets, call 212-279-4200 or visit http://www.thenewgroup.org

Running time: two hours and 50 minutes with two intermissions

This one of the worst plays that I have ever seen. It’s chacters are the worst kind of steryiotype. The plot is highly predicable