Exagoge

Edward Einhorn’s immersive opera/play/Passover Seder is as educative as it is entertaining in its herculean nod to a now lost 2nd century BCE drama.

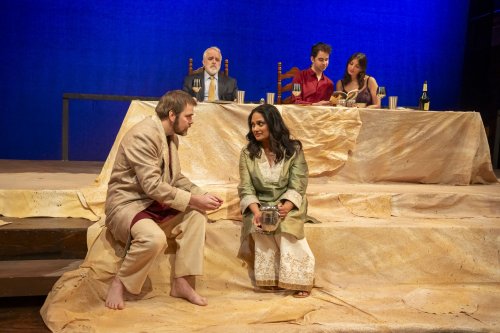

Maxwell Zener, Hershel Blatt, Meena Knowles and Yanniv Frank in a scene from Edward Einhorn’s “Exagoge” at La MaMa E.T.C. (Photo credit: Richard Termine)

[avatar user=”Tony Marinelli” size=”96″ align=”left”] Tony Marinelli, Critic[/avatar]

For a play that is “lost,” we should be grateful for all the research there is to help playwright Edward Einhorn (and his character Zeke) to speculate on how the original Exagoge must have appeared to its 2nd century BCE audiences. In this day and age, our bouts with AI have made us appreciate when humans actually tackle the brainstorming necessary to postulate what is lost. Earlier this season, at Theatre for a New Audience, Annie Dorsen’s Prometheus Firebringer “hired” AI nightly to recreate the missing two plays that were the companion pieces to Aeschylus’ Prometheus Bound…results were without nuance (obviously) and ultimately laughable…and that was Dorsen’s point.

Einhorn’s Exagoge is inspired by Ezekiel the Tragedian’s (an Alexandrian Jew) 2nd (or 3rd) century BCE Greek-language play of the same name which dramatizes the Exodus story incorporating pagan elements. It survives today only in 269-or so lines over 17 fragments. Ezekiel “rocked the boat” by ending his play with the deus ex machina of a phoenix. Although he lived in a multicultural Alexandrian Egypt, he most assuredly riled the Jewish elders for his blatant idolatry, but perhaps his playing to the non-Jews by integrating their tradition of writing in Greek in an art form with its own genesis in Athens found new audiences. This attempt to cater to multiple audiences with the same product (whether you win them over or not) sounds like today’s arts marketing. Refer to any mailer from Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts for a meager 21st-century example.

As we are instructed early on, the meal and the service are divided into 15 sections. The Seder is held in the midst, or as a significant part, of the whole of the play. It is then complemented by the opera portions. Einhorn gets a big assist from composer Avner Finberg’s exotic score and musical director Mila Henry as she leads the chamber sextet from the piano. Tenor James Benjamin Rodgers as Moses, soprano Tharanga Goonetilleke as Tzippora, one of the God voices, and a messenger, and lyric bass Matthew Curran as the Pharaoh, Reuel, and the other God voice are exemplary.

James Benjamin Rogers and Tharanga Goonetilleke (below); Maxwell Zeneer, Hershel Blatt and Meena Knowles (above) in a scene from Edward Einhorn’s “Exagoge” at La MaMa E.T.C. (Photo credit: Richard Termine)

The play proper revolves around the contemporary Seder hosted by Avraham, a professor of Jewish history at Columbia University, in his Upper West Side apartment. Avraham’s composer son, Zeke, arrives late with an unannounced date/girlfriend/significant other Aliya, who just happens to be Muslim (but it’s okay, she’s been to other Seders – of course she has, she too lives on the Upper West Side.) Avraham is a Jewish “chauvinist” if you follow the definition as someone with the unreasonable belief in the superiority or dominance of one’s own group or people, who are seen as strong and virtuous, while others are considered weak, unworthy, or inferior…yes, that’s Avraham, within reason.

Zeke is an insufferable atheist, although raised to be a good Jewish boy (he certainly still remembers all the Hebrew necessary to get him through the Seder responses with his father). He is not bemoaning his lapse in faith, and he is firmly resolved that nothing is sacred, not anyone’s God, nor anyone’s Muhammad. He shows up to the Seder late and with a surprise guest, a Muslim woman (although non-practicing) that he has started dating. Aliya is a librarian who has been helping him in his research for the opera he is composing, but clearly, she sees a Zeke she does not recognize while he is here interacting with his father.

Maxwell Zener as Avraham is a no-nonsense and charming host, comfortable with a room full of people (the audience invited to his Seder). Despite his son trying to get a rise out of him, he manages grace under pressure with little effort. Zener convinces quite easily that he holds fast to his faith. When he poses that question, “what do we learn by repeating the same story, year after year?,” you know he has figured it all out and not just for his benefit, but for ours as well.

Rebecca Jay Caplan, Thananga Goonetilleke, Yanniv Frank and James Benjamin Rodgers (foreground) and Maxwell Zener and Hershel Blatt (at table above) in a scene from Edward Einhorn’s “Exagoge” at La MaMa E.T.C. (Photo credit: Richard Termine)

Hershell Blatt as Zeke is a complete heel. Zener’s warmth is offset by Blatt’s defiance and disagreement that is first nature to this poor little rich kid who has wanted for nothing. While his father is so proud of him and his accomplishments, Blatt plays arrogance and conceit like a badge of honor. When Aliya leaves the Seder, we realize Zeke has nowhere else to go…and so does his father. Zeke “opening the door for Elijah” and the singing together of the “Chad Gadya” are touching moments to end the play.

Aliya finds the balance and the calm to not leave once she realizes her accompanying Zeke is just a way of her boyfriend getting under his father’s skin. Meena Knowles as Aliya finds poise when you least expect it. “My family, especially my extended family, is very different than I am. And I know I act differently around them. But let me tell you this. Some of them are very devout, very sincerely devout. And I respect that. I respect their devotion. And I don’t think you do. I don’t think you respect anyone’s devotion.” She may not be getting Zeke’s respect but when she speaks about devotion, she certainly has gotten Avraham’s.

The production is immersive by design. Seder tables line the entire front row. The main Seder table directly across from the audience has places for three. There are Seder tables on each side of that main center table. Except for where the three actors sit, the tables are for audience members. Behind the long front row the balance of the audience sits in risers, like stadium seating. In the midst of this there are high tables (platforms) for the singers. The entire stage floor is covered with fabric that is meant to evoke sand dunes. Stage left is a cutaway doorframe to signify the entrance to Avraham’s apartment. The ingenious set design by Tom Lee and Grace Needlman suggests endless space – the apartment can very well be the desert. They are also responsible for related puppets.

Rebecca Jay Caplan, Yanniv Frank and Tharanga Goonetilleke in a scene from Edward Einhorn’s “Exagoge” at La MaMa E.T.C. (Photo credit: Richard Termine)

Einhorn relishes providing pageantry. Tanya Khordoc and Barry Weill of Evolve Puppets are instrumental in the staff that becomes a snake and returns to being a staff, the burning bush, the phoenix at the end of the evening. They are all part of an exquisite effect overall. Federico Restrepo’s lighting design enhances the very many mood changes where we go from Seder to opera and back again. Ramona Ponce’s desert-appropriate linen costumes and mask design are exquisite in how they shape Moses in his travels, and the world of Tzippora, Reuel and the Pharaoh.

The manner in which Einhorn has paced the events of the evening is truly an act of precision. Having written the piece, he knows better than anyone the very many arcs there are in the story and how the movement from Avraham’s apartment to the desert and back again…even creating mini-breaks for the Seder…are the result of very careful planning. It succeeds at being a play, an opera, and a sheer spectacle in ways Ezekiel the Tragedian may have never even thought of.

Exagoge (through May 12, 2024)

La MaMa in association with Untitled Theater Company No. 61

La MaMa Experimental Theatre Club

Ellen Stewart Theatre, 66 East 4th Street, in Manhattan

For tickets, visit http://www.lamama.org

Running time: one hour and 40 minutes without intermission

Leave a comment