Lonely Planet

Twentieth-fifth anniversary revival of Steve Dietz’s early AIDS play demonstrates it has not worn well but ultimately has a poignant ending.

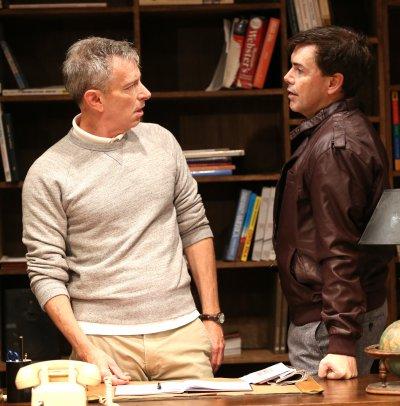

Arnie Burton and Matt McGrath in a scene from “Lonely Planet” (Photo credit: Carol Rosegg)

[avatar user=”Victor Gluck” size=”96″ align=”left” ] Victor Gluck, Editor-in-Chief[/avatar]Keen Company’s 25th anniversary production of Steven Dietz’s Lonely Planet suggests that this two-character allegorical AIDS play has not worn very well. While it was probably quite powerful when first done, it now seems to kill a lot of time getting to its real point and does not warrant its two-act structure.

In Jonathan Silverstein’s production, Arnie Burton and Matt McGrath as two friends who handle their fears of an unnamed epidemic in opposite ways do not seem to connect as real friends would. Ironically, while they are both known for their outrageous over-the-top comic performances, here they remain low-key and rather flat. The play may have been more involving if they had been allowed to give the kind of performances which they are most famous for. The play ultimately has a poignant denouement but it takes a long time getting there.

Set In Jody’s Maps, “a small map store on the oldest street in an (unnamed) American city,” Jody, the owner, appears not to have left the shop for weeks or maybe months, ordering in food and sleeping in the back. His colorful friend Carl, who never seems to tell the same lie about what he does, drops in regularly to see how he is. He begins leaving assorted chairs in Jody’s small shop.

Arnie Burton and Matt McGrath in a scene from “Lonely Planet” (Photo credit: Carol Rosegg)

Eventually we learn that their friends are dying of an unnamed disease and while Carl helps clean out their apartments, Jody can’t even face going to their funerals or memorial services. It becomes apparent that due to his fear of the results Jody has avoided being tested. Jody has taken refuge in his store because of why he loves maps: “They are fixed objects. They have been called ‘surrogates of space.’ They attempt to make order and reduce our reliance on hypotheses. They are a picture of what is known.” Jody – and later Carl – prefers order in the world and fears the unknown. Carl, on the other hand, is taking one chair from each friend who has died as a memento in order to keep their memories alive.

We never learn much about either man. They know each other for years from the shop but do not seem to socialize. They seem to know all the same people but no one other than Carl even calls or turns up on the threshold. In fact, Jody does not seem to do much business while Carl always seems late for whatever he is really doing (an art curator, a glazier in an auto repair shop, a tabloid journalist, a gardener.) Jody has never known what Carl actually does. They say they are going to play “the truth game” but never seem to get around to it, while Carl spins more and more elaborate lies. Each time they meet Jody recounts yet another dream in which he is expected to do a job he is totally unprepared for (firefighter, rock singer, etc.)

And there are those chairs which fill up Jody’s small, well-ordered shop. Just as one is ready to ask why he doesn’t refuse to let Carl store them there, it puts one in mind of Ionesco’s absurdist play, The Chairs, and at that moment Jody begins talking about Ionesco’s play and Carl eventually gets around to reading it. There are other metaphors and symbols, like the Greenland Problem solved by the Mercator Projection World Map: the map distorts the way the land masses really are to enable sailors to navigate using the flat surface. The map shows the world not as it is but as we have come to accept it. This is used as a metaphor for the way the epidemic is being handled in the world outside of Jody’s shop.

Arnie Burton and Matt McGrath in a scene from “Lonely Planet” (Photo credit: Carol Rosegg)

Burton and McGrath never really flesh out their roles, but then the play doesn’t give them much help. McGrath has a different outfit (courtesy of designer Jennifer Paar) each time he appears which is a choice of the production as it is not in the script. Is he taking on the roles of his dead friends? We never know the answer. Burton appears to wear the same clothing so we presume that he has not been home. We surmise that Jody and Carl are gay men but we are told they have never been in a relationship.

Under Silverstein’s placid direction, Jody and Carl never really get angry with each other or show much emotion. The entire play remains basically on one level. Anshuman Bhatia’s setting is very realistic, but on the other hand something more surreal might have been in order. Paul Hudson’s lighting usually telegraphs the time of day, but not always. How much time goes by is never made clear.

Steven Dietz’s play is part of a growing literature of AIDS plays like Angels in America, As If and The Normal Heart. In telling its story allegorically, Lonely Planet is not so much universal now but seems to be avoiding its subject for much of its length.

Lonely Planet (through November 18, 2017)

Keen Company

The Clurman Theatre at Theatre Row, 410 W. 42nd Street, in Manhattan

For tickets, call 212-239-6200 or visit http://www.telecharge.com

Running time: one hour and 45 minutes including one intermission

Leave a comment