Mesquite, NV

In his new play, Leegrid Stevens looks for laughs in the unlikeliest of places, based on a 2011 scandal.

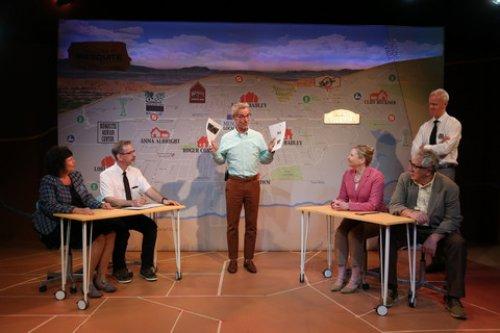

Jackie Jenkins, Michael Gnat, Jeff Paul, Liz Amberly, Alex Dmitriev and Jed Dickson (standing) in a scene from “Mesquite, NV” (Photo credit: Gerry Goodstein)

“This is a play about Mesquite, Nevada.” It was surreal to hear those words on West 36th Street so soon after the tragedy in Las Vegas, where Stephen Paddock, who resided in Mesquite, became the deadliest mass shooter in U.S. history before taking his own life. It was even stranger to learn that the play, which has nothing to do with Paddock’s incomprehensible actions, was inspired by another bafflingly violent episode, one that occurred nearly seven years ago and rocked the Mesquite community to its core. But perhaps the oddest thing of all is that the play, the straightforwardly titled Mesquite, NV, is a comedy.

If you’re unfamiliar with the much earlier horror playwright Leegrid Stevens “loosely based” his work upon, then the laughs should come easily, at first. On the other hand, if you already know what happened in Mesquite, a retirement hub with a population of under 20,000 people, then, sure, the laughs still might come, because Stevens is a clever writer who possesses an enviable amount of playwriting technique, but you could also find yourself guiltily trying to choke them down.

Most of the humor is at the expense of the Mesquite City Council and its steely-eyed mayor Linda Hadley (Liz Amberly) who could be accurately described as a Margaret Thatcher wannabe, if she had any idea who Margaret Thatcher was. With rapacious resolve, she has set her sights on doing something no other mayor has ever done in the entire history of Mesquite: win a second term. She is assisted in this quest by her right-hand toady (Jeff Paul), the financial backing of a shady resort magnate (Jed Dickson), and an underwhelming pool of potential challengers, led by Will Brown (the wonderful Joe Burby) whose hapless sincerity is seemingly no match for the mayor’s small-town realpolitik.

Liz Amberly and Jeff Paul in a scene from “Mesquite, NV” (Photo credit: Gerry Goodstein)

But then, fed up with the status quo, Anna Albright (Jackie Jenkins), a former police officer with a sterling reputation, decides to mount a campaign against the corrupt mayor, which, of course, sends Hadley’s mind into dastardly overdrive. Obsessed with trying to smear the apparently unimpeachable Albright, Hadley enlists the aid of a feckless bean counter (Michael Gnat), and together they uncover the mother of all scandals–well, the mother of all scandals in Mesquite, Nevada. Either by accident or knowingly, Albright submitted an approximately $90 travel reimbursement for a City Council business trip she never took.

This petty violation gives Hadley just the leverage she needs to extort her rival out of the mayoral race, with the help of an overweening journalist (Robert Meksin), who fancies himself both Woodward and Bernstein. But when Hadley’s machinations lead to unintendedly bloody consequences, she becomes even more desperate to save her imperiled political career, as her constituents, especially Albright’s fearlessly vocal best friend (Jill Melanie Wirth), sharpen their pitchforks.

If it all sounds a little Coen brothers, that’s intentional. In a press release, the films of the derisive duo are cited as an influence for Stevens’ work. And, at least for the first half of the play, it’s a pretty solid facsimile.

Early on, director Thomas Coté keeps everything fast-paced and ridiculous, with a lot of support from his design team. In particular, Jennifer Varbalow’s tourist-map set of Mesquite, which marks the location of golf courses, government offices, the Senior Center, the Oasis Resort Hotel Casino, a local sports bar favored by the mayor’s ex-husband, as well as the homes of all the key characters in the play, offers a nice sense of the community’s compact and suffocating insularity. And, as part of a stream of Brechtian devices, Laura Hirschberg’s cutouts of everyday objects–telephones, a ketchup bottle, cigarettes, and even a whole person–are a two-dimensional joke that never grows stale.

Jackie Jenkins and Robert Meskin in a scene from “Mesquite, NV” (Photo credit: Gerry Goodstein)

But the overall effect of the many, many Brechtian devices Stevens and Coté employ, which also includes continual, overtly stated reminders that we’re watching a play is a huge problem because in distancing the audience from the narrative, the two collaborators force us to wonder whether or not we should be laughing at the self-defeating antics of Mesquite’s geriatric citizens who again experienced a real tragedy. And when much earlier than expected, the dark moment does arrive at the end of Act I, we really wonder. As the Coen brothers are often accused of doing, Stevens is punching down, and it doesn’t feel right watching the pummeling.

As for the second act, Stevens strains for a profundity that he’s not prepared to deliver, and Coté seems a little lost as he struggles to help the actors find it, too. Only Alex Dmitriev, as a befuddled councilman whom the mayor tries to make her patsy by entrapping him with his own decency, understands the notes Stevens wants to play. Perhaps because he’s the only one not trying to bring a caricature to life.

In fairness, I may not be giving Stevens and Coté enough credit. Maybe, in true Brechtian fashion, it was always their intention to implicate the audience through its laughter, in order to make a bunch of East Coasters on West 36th Street understand how reflexively they’ll take part in the mockery of flyover country. In other words, they used Brecht to get us.

Or, maybe, what really happened is that Brecht got them.

Mesquite, NV (through October 28, 2017)

The Workshop Theater

The Workshop Theater, 312 West 36th Street, 4th Floor East, in Manhattan

For tickets, call 866-811-4111 or visit http://www.workshoptheater.org

Running time: two hours and 10 minutes with one intermission

Leave a comment